Introduction

In this report, we discuss a recent case involving the detection and management of Acanthmoeba Keratitis (AK) and highlight the usefulness of a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay in the identification of AK. AK is a rare but severe eye disease that can cause permanent ocular damage, blindness, and loss of the eye itself.1 Acanthamoeba is a free-living organism found in all areas of the environment including air, water, and soil.2 Acanthamoeba takes on two forms: trophozoites and cysts, and the trophozoite stage is characterized by protozoan growth and reproduction.3 Infection occurs when trophozoites contact and bind to a damaged corneal surface, such as with contact lens use and exposure to contaminated water sources. Cysts subsequently form, which withstand harsh environmental conditions leading to persistent, treatment-resistant infections. AK is notoriously difficult to diagnose clinically as it lacks pathognomonic features in early stages, often masquerading as other more common infectious processes. Laboratory testing is challenging as Acanthamoeba does not grow on routine culture media, and specialized media such as non-nutrient agar with E. coli overlay often requires prolonged in vitro incubation and, furthermore, are not widely available. In vivo diagnosis can otherwise only be confirmed through confocal microscopy which is similarly difficult to obtain and interpret and currently unavailable in Mississippi.

Case Presentation

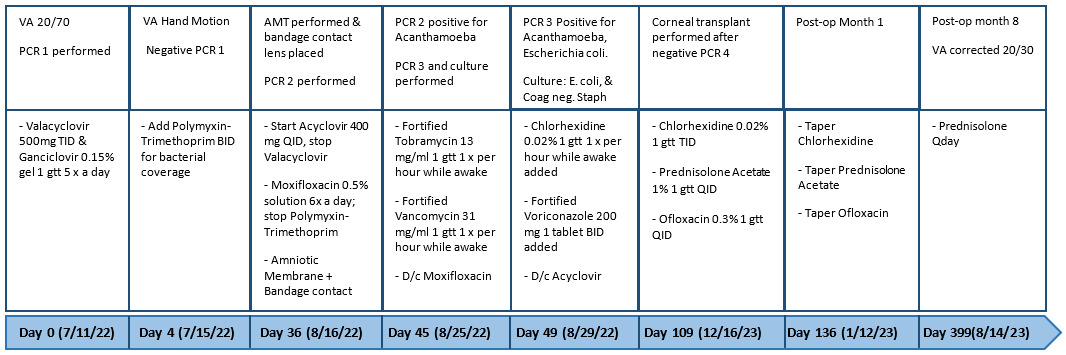

A 55-year-old female presented with complaints of blurry vision, pain, excessive tearing, and sensitivity to light in her right eye. She had previous ocular surgeries in the distant past including cataract surgery with anterior chamber intraocular lens placement, and she used contact lenses for refractive error. Her symptoms appeared five days prior to her initial presentation and were slowly progressive. She endorsed showering in her lenses, but she denied swimming in contacts, exposure to outdoor water, or using tap water for lens hygiene. The patient reportedly halted use of her contact lenses when symptoms first appeared. Examination revealed mild corneal edema, ulceration, and cellular infiltration suggestive of infectious keratitis. Initially most concerning for viral etiology, the patient began presumptive treatment for potential herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis with ganciclovir gel and valacyclovir tablets. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was performed to detect possible infectious pathogens.

Frustratingly, the initial PCR resulted negative. At the four-day follow-up visit, the patient reported a dull aching pain and otherwise unchanged severity of symptoms. She reported compliance with medications. Lacking significant clinical improvement, she began polymyxin-trimethoprim eye drops in addition to previous medications to cover for potential bacterial coinfection.

At subsequent follow-up, symptoms pain and blurry vision had worsened, and the keratitis had worsened clinically with vision decreasing to only hand motions. Without a clear diagnosis, a second PCR test was performed, and an amniotic membrane transplant (AMT) was placed to treat persistent ulceration. Antivirals and antibiotics were continued. The repeat PCR identified a low microbial load of Acanthamoeba, and a third PCR test was reflexively performed which also showed Acanthamoeba. Hourly chlorhexidine and voriconazole eye drops was begun. Antibiotic coverage was also escalated when suspicion for bacterial coinfection was confirmed as E. coli and coagulase negative Staphylococcus. Viral infection was excluded and acyclovir was discontinued.

After months of treatment and a final PCR test detected no microbes, a full thickness corneal transplant was performed for residual corneal scarring. At the end of treatment, the patient had resolution of her symptoms, and her vision improved back to 20/30.

Discussion

Because of its fastidious nature, Acanthamoeba is a difficult organism to isolate by corneal scraping and requires specialized culture media that are either unavailable or only obtainable as special order at Mississippi hospitals. Quick and accurate identification of this serious eye infection is crucial for proper medical and surgical management as well as good prognosis.4 Consequently, other diagnostic methods are needed which are both rapid and easily accessible. The use of PCR assays in the treatment of infectious keratitis has been found to significantly increase pathogen-detecting sensitivity.5 Previously only available at tertiary referral centers or via a time-consuming “send-out,” PCR testing for infectious organisms was not expedient. However, recently, new PCR assays have allowed organisms that are poorly detected through traditional cultures to be identified in a timely manner.4 A proprietary PCR test with large assay panel including bacterial, fungal, viral, and protozoal pathogens has been introduced (HealthTrackRx, Denton, TX). This new PCR test is shipped overnight to central labs, and testing results are available online within 48 hours, often sooner than results are made through routine culture. Thus, PCR testing for AK can be performed by any eye care provider, including in the rural setting, and testing supplies are supplied to clinics at no charge.

Our case utilized the HealthTrack Rx PCR assay, but it required a repeat sample to make the diagnosis, highlighting the fact that, even with PCR testing, the organism can be difficult to identify, and multiple tests are often required.6 This same assay also successfully identified bacterial co-infection, further highlighting its utility in guiding appropriate antimicrobial regimen.

The treatment course for AK is very demanding, requiring compounded eye drops administered hourly before being slowly tapered for six months or more. After the diagnosis of AK was made and treatment was begun, our patient followed a typical clinical course of AK including months of topical chlorhexidine therapy. While our patient required corneal transplant for scarring after clearance of AK, delayed diagnosis and treatment leads to worse visual acuity outcomes and higher rate of corneal transplant.7

Our case of AK is significant because it confirms the presence of this previously unreported disease in Mississippi and, therefore, suggests the need for clinicians to have an increased suspicion in contact lens-wearing patients presenting with infectious keratitis. This case of AK ostensibly arose from contact lens use with exposure to municipal tap water while showering, and it illustrates the need for appropriate counselling of patients regarding best contact lens use practices including avoidance of showering, swimming, or sleeping in contact lenses.