Introduction

The history of the Colored King’s Daughters Hospital (CKDH) of Greenville is both fascinating and compelling. Its lifetime spanned the years between the United States Supreme Court decisions of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) in a location where cotton dominated the economy. Everything occurred against the backdrop of the Jim Crow South. The CKDH lived through World War I, the 1918 Great Influenza epidemic, the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, the Great Depression, World War II (WWII), and the Korean War. It began with a group of charitable women and ended with a hospital that is still functioning today as the city’s only hospital. As its lifespan meandered through the years like the nearby Mississippi River, the CKDH’s timeline and story touched or intersected with local city and county governments, the Mississippi Supreme Court, a Founders Group member of the American College of Surgeons, a famous author who chronicled the Civil War, an ex-slave and Confederate soldier who befriended a U. S. President, a world-famous multi-specialty clinic, and a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist. All that remains of it today are a cornerstone, one document, the ground where it stood, and this story. The story has never been told.

During the first half of the 20th century, strict racial boundaries kept hospital care segregated in many locations, including the Mississippi Delta. There is a significant amount of scholarship on the plight of hospitals that served black patients during this time period.1 Segregated, typically inferior, facilities for black patients tended to be black-owned and operated or white-owned and operated. Both models were components of the evolutionary process in healthcare access from Reconstruction to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Charity and philanthropy played important roles in these hospitals nationally, regionally, and locally. The CKDH began as a black-owned and operated facility for black patients in the Delta and evolved to a black-owned and white-operated facility for non-white patients in the Delta. Other facilities in the Delta which served black patients – Rosedale’s Hospital for Colored People, est. 1903 with 8 beds, and Greenwood’s Greenwood Colored Hospital, est. 1912 with 12 beds – were white-owned and operated facilities for black patients.2–5 However, the CKDH appears to be the only one originating from a black charitable women’s group. It predates the better-known Afro-American Sons and Daughters (AAS&D) Hospital in Yazoo City (1928-1966) and the Taborian Hospital in Mound Bayou (1938-1967).6 Both hospitals were organized and developed by black fraternal organizations – the Afro-American Sons and Daughters and the Mississippi Jurisdiction of the International Order of Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor. Primary funding was through programs of health benefits by subscription for their members.6–8 These facilities helped address the significant need for healthcare for Mississippi’s black citizens. In Greenville, the need was no less significant. This need had been addressed years earlier by the formation of the CKDH.

Background

Detailed and official records of the CKDH are hard to find. No information on the CKDH is known to exist at the Mississippi Hospital Association, Mississippi Department of Health, Greenville History Museum, Washington County Tax Assessor’s Office, Washington County Health Department, or in the collections at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH). Through online database searches; personal research visits; on-site confirmation with archivists, research librarians, museum curators, county tax assessor employees, and health department officials, the author has verified this lack of historical records.

The CKDH was initially founded and supported by the efforts of the Colored King’s Daughters (CKD). The background of the King’s Daughters organization in Greenville is relevant to this history. The International Order of the King’s Daughters and Sons (IOKDS) was organized in New York City in 1886. Their motto is: “Look up and not down; Look forward and not back; Look out and not in; Lend a Hand”.9 The hospital movement of the white King’s Daughters Circle No. 2 (KDC2) in Greenville grew out of the charity and philanthropic efforts of a group of local women in 1892. This progressed through two cottages that were refurbished and furnished for healthcare purposes. KDC2 gained a national charter from the IOKDS in 1895 and a state charter from the Mississippi Branch of the IOKDS in 1897 as the group gained members and increased its funding. These efforts culminated in the construction of the white King’s Daughters Hospital (KDH) in Greenville in 1905.10–14 The hospital was replaced in 1926 and remains today as the West Campus of Delta Health System.

There were other white circles in Greenville. Circle No. 1 was likely formed before KDC2 and focused on charity. There is evidence of their activity in 1898 and 1903, but they apparently did not apply for a national or state charter.10,15,16 Circle No. 3 was organized in 1901 as a junior branch of KDC2 and officially became Circle No. 3 about a year later.16–18 After 1906, Circle No. 1 merged with KDC2, and it is likely that Circle No. 3 also folded into KDC2.10 KDC2 continued their work through the years and evolved through societal and cultural changes. They sold the KDH in 2005 and function today as a charitable foundation independent from the state and national organizations while retaining the original name.19,20

The IOKDS has no records prior to the 1970’s due to a fire at the organization’s New York City headquarters prior to relocating to Chautauqua, NY.21 There is no mention of black circles in the history of KDC2 compiled in commemoration of their 100th anniversary in 1994.10 However, black circles did exist. In 1909, W. E. B. DuBois noted “The King’s Daughters and Sons have many colored circles.” These circles were in New York City; Toledo, OH; Frankfort, KY; Natchez, MS; and Austin, TX. Further, he stated “There is one Circle of the King’s Daughters in Greenville, Miss., and they together with the white Circles of that city have built and operate a hospital.”22 No evidence has been found to support that statement. In the 1931 history of the IOKDS, the report of the Mississippi Branch noted, “At one time there were several colored Circles. There is no reference in the minutes to the existence of any at the present writing.”14

The CKD and the CKDH are not nearly as well documented as KDC2 and the white KDH. Fortunately, information sits in oral history transcripts, newspapers, deed records, local government records, and other less well-known places. With the strict boundaries of racial segregation, the philanthropic efforts of KDC2 in hospital care were not available to black citizens. However, the movement of the CKD to provide healthcare proceeded along a separate, but parallel, track of similar methodology. Its footprint was smaller than that of its white counterpart and usually delayed by a few years.

Beginnings and Early Years: 1898-1927

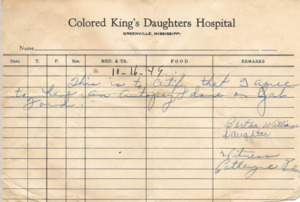

In 1898, William McKinley was President, the Spanish-American War took place, and Marie and Pierre Curie announced the discovery of radium. Also in 1898, on December 12, Rev. C. B. Anderson organized a “circle of Kings Daughters among the colored people of Greenville.”23,24 (FIGURE 1) There would be multiple circles within the CKD over the next ten years. These circles were identified by names, numbers, or both. It is unknown if there was an actual formal affiliation with the IOKDS national and state organizations through charters as those records do not appear to exist. Through charitable efforts, the motivated women of some of these circles organized and developed resources and healthcare facilities for black patients. These efforts and facilities set the groundwork and were the predecessors of the CKDH.

After the formation of the CKD in 1898, the movement towards hospital care for Greenville’s black citizens begins to come to light, literally. On December 2, 1902, at the Greenville City Council’s (CC) regular meeting, an agenda item was “the matter of water and lights at the Colored Kings Daughters Home.” The CC referred the matter to the “Committee on Lights and Water with power to act.”25 The newspaper reported this as “The colored King’s Daughters asked for a light near their home across the railroad on Alexander Street. They also asked for an allowance after this month.”26 Thus, in a similar manner to their white counterparts, a house had been procured and set up as a “Home” and was referred to as such. This is the earliest version of the CKDH. However, in contrast to their white counterparts, their trials and tribulations would be quite different.

By July 1903, one circle, the Helping Hand Bailey Circle of the Colored King’s Daughters, was renting a “home for our sick and disabled” on the corner of Blanton and Gloster Streets. Their stated goal at the time was to “erect a building of our own.” The leadership of this group was Alice E. Williams, Leader, and Alma V. Bailey, Secretary. These are the earliest individuals’ names associated with the CKD healthcare movement. They published a notice in the newspaper to “thank the public for its kindness shown in assisting in the way of renting and furnishing” the Home and invited the public to visit. Tentative future plans included building a facility on a lot on North Shelby Street donated by Phillip Williams, who is believed to be Alice’s husband.27

The CC did not act quickly on the 1902 request for financial aid. At its October 6, 1903, meeting, they appointed Councilman E. R. Wortham to investigate and report on the “application for aid.”25 The newspaper reported this as simply, “Mr. Wortham was appointed to look after the needs of the colored King’s Daughters.”28 By November 3, the CC felt sufficiently advised to approve a monthly stipend of $15 commencing December 1 to “Circle No. 1 of the Colored Kings Daughters of Greenville.”25 This circle appears to be either another circle of the CKD or renaming of the circle with which Alice Williams was affiliated. It had taken a year to obtain the CC’s support at $15/month. Overall, however, the group appeared to be adept at obtaining financial and material support for this project. Several prominent citizens were generous donors, and school children brought food and clothing to the “King’s Daughters Home for old colored people.”27,29 After Thanksgiving, 1903, Alice Williams, on behalf of the “colored King’s Daughters Circle”, published a public appreciation in the newspaper for the food donations for the “inmates of their home.”30 In the summer of 1904, “An Appeal from the Colored King’s Daughters” was published in the newspaper. This appeal was directed to “Pastors, Members, and Friends.” It stated: “If we would succeed as a race, our interest and general welfare must be guarded. We must strive to help ourselves then others will readily help us.” A meeting was called for the following evening at a local church “to inaugurate plans to perpetuate this laudable christian (sic) enterprise.” Although not explicitly stated, the meeting appears to be in regard to the consolidation of the multiple circles into one, the hospital movement, or both in order to be more effective. The signers included circle representatives (J. Frazier – Circle 1, C.A. Johnson – Tuxedo 2, L. Johnson – Circle 3, S. Rains – Circle 4), officers (Mrs. A. E. Edwards – cor. secy., K. Sales Lewis – state leader), members (Mmes. B. T. Lewis, Ida Lewis, A. King), and pastors (Revs. A. E. Edwards, Harris, Jno. J. Morant, P. Williams).31 Many of these names will play prominent roles on the journey to establish the CKDH over the next few years. Specifically, Sallie Rains will ultimately lead Circle No. 4, which will establish the final version of the CKDH. Also seen here are four different circles within the black community, much like their white counterparts.

The exact outcome of that July 28, 1904, meeting is unknown. The issues were, in all likelihood, discussed, and it is unlikely everything was resolved. There was a monthly allowance going to the CKD for this work from the local government – the CC and the Washington County Board of Supervisors (BOS) – and distribution of funds within the CKD may have been an issue. From the outset, both the CC and the BOS essentially contributed equally. These allowances were nearly always current. Allowances were also made to KDC2 by both the CC and BOS but at a higher rate. The initial allowances were $15 for the CKD and $25 for KDC2. In late 1904 and early 1905, the amount for KDC2 had increased to $50, while that for the CKD remained at $15.32–34 As the allowances increased over the years, the discrepancies in the amounts would always be the case.

A controversy arose within the CKD in April 1905 and was aired publicly in the newspaper. This issue was important because a shift in control of the hospital movement within the CKD is demonstrated, and the issues behind it are explained. An open letter to the public is published from the officers of the Union Circle: Sallie Rains, Leader; Lucy Brown, Vice Leader; Delila Daniels, Secretary; Essie Forbes, Ch. H. B. At the July 28, 1904, meeting, Rains (Mrs. Sam) had identified with Circle No. 4. The letter is in response to “diverse reports” that were “derogatory to our laudable efforts to succor and care for our indigent sick and helpless.” The women explained that the “Union Circle controls and receives all communications from subordinate circles.” As such, Alice Williams, leader of Circle No. 1, had placed the Home in the care of Rains and the Union Circle once her health deteriorated in June 1904. Williams died shortly thereafter. Rains and the Union Circle began operating the Home and had received no funding from the CC and BOS until the previous month. As the Home was “too small and inconvenient” for their present needs, they relocated to “new quarters, thus providing better accommodation for the sick, with regard to cleanliness, pure air, and quiet.” They rented “a large and roomy house” for $14/mo. Further, they outlined hoped-for future plans to include an operating room (OR), wards for paying patients, and a trained nurse. They welcomed any physician to help in the effort and explained that they were not working for profit nor for any particular physician. All donations, monetary and material, were used in the new Home. They invited the Mayor, Councilmen, and all physicians to visit and inspect the new Home and welcomed any suggestions that may contribute to its success.35

Two weeks later a rejoinder appeared in the newspaper. It was written by Phillip Williams. He denied that Alice Williams had “delivered King’s Daughters Circle No. 1 to King’s Daughters Circle No. 4” as there was not a Circle No. 4 when she died. He explained that Circle No. 1 had been doing the work since June 1903 without assistance from Circle No. 4. Now that there was a Circle No. 4, he invited them to “join in the good work to care for the poor and needy.” However, he asked what had become of the CC and BOS allowances that Circle No. 4 had collected as there was no other Home. He accused them of collecting the allowances to deprive Circle No. 1 of funding and of soliciting the patients/residents to move to their new Home. He further stated that Circle No. 1 did not request financial support from the CC and BOS until 8-9 months after opening the original Home by which time they were overloaded. Now that there was a Circle No. 4, he invited them and “everyone to help in this good good (sic) work.”36

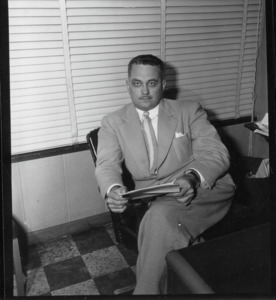

This exchange demonstrates conflict within the CKD due to change and progress. Alice Williams was a pioneer, established the concept as workable, and began the effort. Funding from local government appeared, charitable donations materialized, and black patients/residents received care. Not surprisingly, the facility and resources were quickly outgrown and unfortunately, Alice Williams died. Importantly, the movement did not, and Sallie Rains and her associates carried on. (FIGURE 2) A larger facility was acquired, and larger scale plans were made. Apparently, an irritant to Phillip Williams and his followers was the fact that Circle No. 1 did not receive sufficient credit for their efforts. Nonetheless, he was able to acknowledge the greater good. Fortunately, progress did not stop. The CC appointed a committee to adjudicate the situation, likely regarding who receives the funding – Circle No. 1 or Circle No. 4 (Union Circle). This adjudication resolved in favor of Circle No. 4 and the new Home at 1307 Alexander Street.37,38

The earliest report of the hospital endeavor was published in the newspaper by Sallie Raines (Rains) and Delila Daniels in July 1905. The public report covered part of May and all of June. (FIGURE 3) Twenty-three patients had been cared for which included charity (13), county (3), and pay patients (7). It is not clear what the classification “county” signifies. It may designate employment status or perhaps some type of involvement by the county in an employee’s healthcare bills. Charitable donations totaled $105.35 from the aforementioned CC and BOS, Odd-Fellows, Masons, Carpenters Union, Knights of Pythias, prominent white Greenville businessman Edmund Taylor, and the general public. Expenditures were $96.35.39 It was a small but important step. This fledgling report is a study in contrasts to the program of the white Washington County Medical Society in the same newspaper on the same day. It lists presenters, including two guest speakers from Memphis, and their presentations. Topics were medical treatment of gunshot wounds, the value of routine blood examinations, blennorrhea, diabetes, and pericarditis with effusion.40

By August 1905, the CC monthly allowance for the white King’s Daughters (circle not specified but clearly connected to their hospital effort) was at $100 and that for the CKD remained at $15.41 The efforts of the CKD continued unabated. In the spring of 1906, Delta Epsilon (Mrs. R. L.) McLaurin of Vicksburg visited Greenville where she stayed with her friend, Mrs. LeRoy Percy. McLaurin was the daughter of a former Mississippi governor, wife of a prominent Vicksburg attorney, and a leader in the IOKDS at the national, state, and local levels.14,42–44 During this visit, McLaurin took the time to visit the “colored King’s Daughters Home to see the progress they were making.”45 Although details of the visit are missing, this is one of the rare visits to the black facility by prominent whites which was documented at that time. The “progress they were making” must have been satisfactory because the CKD continued to grow and develop.

On June 2, 1906, Sallie Raines and Deliah (Delila) Daniels published an annual report of the CKD in the newspaper. The report covered April 1, 1905 – May 10, 1906, and was divided into two sections: healthcare activities and treasurer’s report. With regard to healthcare, 176 patients were cared for and categorized as city, county, pay, railroad, and charity. The data was further stratified by pay patients per physician, charity patients per physician, patients collected from and not collected from, disabled patients cared for, and deaths categorized by sex (11% overall mortality rate from April to December 1905). Money collected and money due totals were listed. The report listed eight physicians (Drs. Payne, Shivers, Smythe, Brown, Toombs, Miller, Fulton, and Stone) who treated patients in the CKD Home.46 Three of these physicians (Drs. Brown, Miller, and Fulton) were black, and only Brown treated paying patients.6,47,48

The treasurer’s report was similarly detailed. Monetary contributions were received from the CC and BOS, colored Odd Fellows, Pythians, Household of Ruth, Sons and Daughters of Jacob, Ladies of Honor, carpenters’ union, New Hope Baptist Church, Masons and Rev. Morant, and members of King’s Daughters and Republic. Material donations were: Mr. Butler, plumber – 1 ton of coal; Alabama Coal Co. – 1 ton of coal; Mayor and Mrs. Yerger – half ton of coal; Mr. Geo. Robinson – half ton of coal. The total for the CKD Home was $774.40 with $769.60 disbursed leaving $4.80 on hand. The nurse, Mrs. Katie S. Lewis, was paid $10.05. Appreciation was expressed to the CC, BOS, and the public for their “liberal patronage.”46

A number of observations can be made from this report. Both white and black physicians treated black patients in the CKD Home. This was not a purely charity enterprise although it depended heavily on monetary and material charitable donations. The single largest funding source was the monthly allowances from the CC and BOS, but generating income, when possible, was important. Again, it is not clear what the patient categories mean, but it would appear to be a classification based on employment status which may have signified ability to pay healthcare bills or participation of the employer in some manner regarding an employee’s healthcare bills. Both local government and industry had no other facilities locally to care for their black workers, especially those injured on the job. Whether employers participated in their employees’ healthcare bills is not known. “Paid nurse” Mrs. Katie S. Lewis is seen for the first time. This clearly would have upgraded care at the CKD Home. The public appeared to be aware of this healthcare resource and were utilizing it. The CKD hospital effort had now taken on an identity, had made significant progress forward, was aware of the future need for growth and expansion, and had proven to be adept and persistent in soliciting support.

The nursing staff would be a foundational pillar of the CKDH effort throughout its lifetime. The earliest mention of trained nursing care is the desire to “hire a trained nurse in the Home” in April 1905.35 This hiring comes to fruition shortly thereafter when K. (Kate/Katie) S. (Sales) Lewis was noted in the 1905-1906 treasurer’s report.46 Although the historical record is somewhat fragmentary and imperfect, the available evidence suggests that Lewis was the first paid nursing provider for the CKD healthcare facility when it was the Home as early as 1905.24,49–51 She is not to be confused with the Kate E. Lewis who was a well-known schoolteacher at Number Two School in Greenville during that time period.50,51 Prior to this (1902-1905), the sick care that was necessary at the Home was likely provided by the skill, compassion, and benevolence of the women of the CKD. Lewis was probably the only nurse at the facility prior to moving into the CKDH in 1908, and it is not known if Lewis transitioned into the CKDH when it opened. In the 1913 City Directory, Lewis is listed as living at 314 N. Broadway with her occupation as “trained nurse.”52 In the 1920 U. S. Census, she is listed as living at 406 N. Broadway, age 47, occupation “trained nurse”, and employer “families”, which suggests she may have moved to private-duty work.53 Her name is memorialized on the CKDH cornerstone.8

At this time, the CC and the BOS increased the monthly allowances to the CKD to $20 and $25, respectively.34,54,55 The CKD held an annual “linen shower and ice cream entertainment” in August 1906. A public invitation was published in the newspaper. They asked “their white friends to make donations of needed supplies for the Home.”56

On February 5, 1907, City Health Officer Percy W. Toombs, M.D., delivered an in-depth report on “matters pertaining to the health department of the city for the year 1906.” He noted that “charity patients at the white King’s Daughters hospital have received the most cordial and considerate attention.” He then went on to address the situation at the CKD Home. He stated that “the best results have been obtained under the existing circumstances.” However, he explained that the “means for caring for the colored sick are altogether inadequate and quite unsatisfactory.” He recommended that a committee of three from the CC confer with a committee of three from the BOS to explore building an annex to the white KDH where the “colored indigent of Greenville and Washington County could be cared for” and where “colored pay wards could be maintained.” He further added that “this plan is adopted by every county and city hospital in the United States.”57 This plan was never adopted. The CKD had taken matters into their own hands and were poised to make a difference.

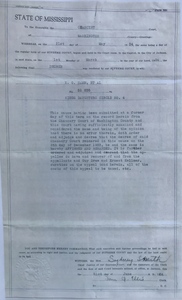

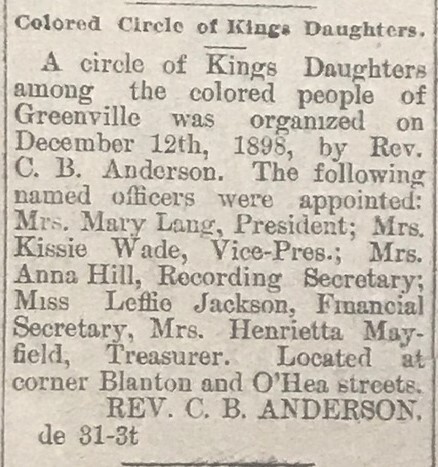

About a week earlier, on January 28, 1907, the Trustees of the CKD of Greenville (Sallie R. Raines, Delia Brown, Louisa Craig, Matilda Miller, Mrs. L. J. Williams, Mrs. K. E. Daniels, Lucy Brown, Lavinia Johnson, Caroline Johnson, Mary Walton, and Frances Cowan) took title to property described as Lot 5 of Block 3 of the Mackenzie addition in Greenville from Francis X. and H. Holmes for $750. This is the vesting deed of the property for the CKD which would be the future and final home of the CKDH.58 (FIGURE 4) The CKD Home continued on its mission. On April 20,1907, the CKD Union Circle No. 4 published its report for “Part of 1906-1907.” Writing for the group, Sallie Rains (Raines) and Delilia (Delila, Deliah) Daniel (Daniels) showed continued progress. A total of 89 patients were cared for with 14 deaths (16% overall mortality). They cared for charity patients at the Home and paying patients at both the Home and outside of the Home, which means they also did home health nursing. Of the total, 51 were paying patients (57%). The group also gained 6 new members. Income sources were the CC and BOS, Sons and Daughters of Jacob, Household of Ruth, white school children, colored school children, pay ward, Knights of Pythians No. 8, Masons, Friend Mrs. C. Johnson, dues from members, and general collection. Total income was $1074.60 with 45% coming from paying patients and 44% from the CC and BOS monthly allowances. Total disbursement was listed as $1041.60 leaving on hand $33. Rent ($170.50), nurses ($223), payment on the lot ($210.45), and incidentals ($468) comprised the disbursements (which totals $1071.95, an unexplained discrepancy). The only debt listed was the $539.55 balance on the lot. As before, appreciation was expressed for the material donations: Greenville Ice and Coal Co. and school children No. 2 – 62 lbs. sugar, 20 lbs. rice, etc.; school children No. 4 – groceries, $1.80; Goyer Co. – 1 barrel of apples, 1 crate of cabbage, meat, $2.50; Delta Bakery and Sievers Bakery – bread; white and colored friends – linen shower; Richard Jackson – work amounting to $10; Alabama Coal Co. – 1 ton of coal; Mr. Hirsch’s meat market – meat; Mrs. Underwood – groceries.59

On August 24, 1907, the CKD, being “desirous of securing from the board of Supervisors of said county assistance in the charitable work for which said Kings Daughters is organized, and said board of Supervisors is willing to lend such aid for the purpose of having a home for the colored sick of said county”, conveyed the deed to the BOS for the payment of the debt on the lot. However, it was “understood that said property may be used by said Kings Daughters as a home for the sick and afflicted, but that whenever the same shall cease to be so used said board of Supervisors shall become thereby vested with the perfect title to said property for its own use and benefit.” Further, “said board of Supervisors, in accepting this conveyance, agrees to reconvey said property to said Kings Daughters at any time hereafter upon payment to said board of Supervisors all amounts paid out by it, as hereinbefore agree to be paid, as well as any and all amounts which may be here after paid out or expressed by said board in improvements, or otherwise, on said described property.”60 This arrangement would now allow the CKD to be free of their largest debt, enable the development of the CKDH, preserve the purpose of the property, and allow them to reclaim the title by reimbursement to the BOS of expenses related to the property.

In December 1907, the annual linen shower was held for the benefit of the CKD. Night gowns, night shirts, sheets, towels, and pillowcases were specifically requested. Interestingly, the event was held at the home of Mrs. E. P Brown, wife of black physician E. P. Brown, who practiced in Greenville from 1895 to 1915.47,61 Brown had treated patients at the CKD Home, and his wife was involved with the CKD and their hospital effort. It is possible that Brown supported the effort and treated patients at the CKDH until he left Greenville, but documentation of this has not been found.

Steady progress had been made from 1898-1907 by the determined efforts of the CKD in this endeavor. Now, it appeared that the CKDH was going to be a reality.

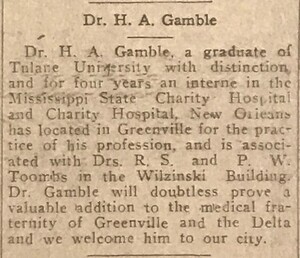

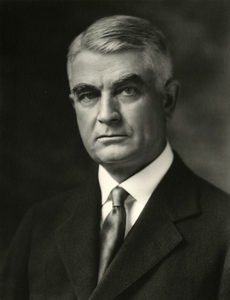

In August 1907, Hugh Agnew Gamble, M.D. settled in Greenville. He would remain in Greenville for the remainder of his life and would become a major force at the CKDH. Gamble, a native Mississippian, had received his medical education and training at Vanderbilt, Natchez Charity Hospital, Tulane, and Charity Hospital in New Orleans (CHNO). In New Orleans, he trained under the renowned physician and surgeon Rudolph Matas, M.D., FACS.62–64 Gamble’s life has been chronicled and detailed elsewhere.64 Gamble initially associated with Drs. R. S. Toombs and P. W. Toombs.62 Within a few months, he had joined the county medical society, assumed the practice of P. W. Toombs when Toombs moved to Memphis, and was appointed Railroad Surgeon by the Southern Railway of the Illinois Central system.65,66 (FIGURE 5) As Gamble developed his practice, house calls and home deliveries were common, and he utilized the resources and facilities at the white KDH and possibly the CKDH to a degree. Having trained at two charity hospitals, Gamble was well aware of the distribution of healthcare based on race and economic status and that this could easily result in the option of “no care.” He also understood that the option of “no care” was not an option for him as a physician.

Among the noteworthy events in United States history in 1908 were the births of Thurgood Marshall, Lyndon Johnson, and Michael DeBakey; the launching of the Ford Model T; and the report that infamous outlaws Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid had died in Bolivia. The year 1908 would also prove to be the year that the dream of the CKD (used interchangeably by this time with King’s Daughters Circle No. 4 [KDC4]) to have their own healthcare facility would be realized. At its February 4 meeting, the CC appointed a committee to confer with a committee from the BOS in “assisting the colored King’s Daughters in improving their hospital facilities.”67 At the March 30 meeting, Dr. E. C. Smythe, City Health Officer, presented a “rough plan for a colored hospital” in the form of a sketch.68

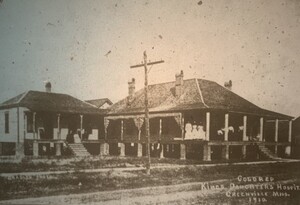

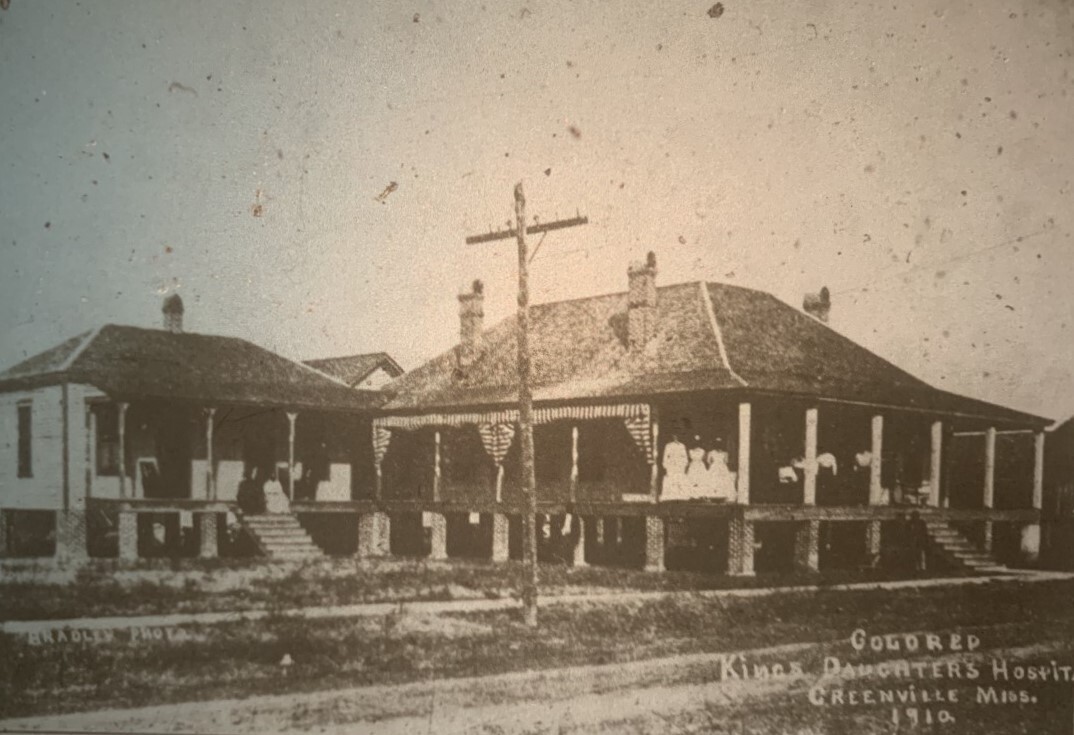

The actual construction of the CKDH has been somewhat of a mystery, as the early years of the CKDH are the least well documented. Despite the existence of a cornerstone, various stories circulated over the years as to whether the building on the CKD lot was new construction for the specific healthcare purpose or renovation and conversion of previous construction such as an old house. The answer is found in the CC and BOS minutes during 1908. On April 7, the CC requested local contractor/builder J. W. Bermingham “make plans & specifications at a cost of not over $20” and for the clerk to advertise for bids for the construction.34 By May 5, the plans had been completed, Bermingham was paid $20, and the lowest bid of $1670 from local businessman/builder T. P. Reynolds accepted.34 A cornerstone was laid, and two months later the construction on the CKD lot was completed. On July 2, the CC appointed a committee “to examine and report upon the building erected as a hospital for the Colored Kings Daughters.” The committee was to “examine the work with a view to plans and specifications.”34 The inspection obviously met with approval because payment to Reynolds for $1670 was authorized on July 7 with the BOS paying half the previous day.34,69 On July 13, bids for plumbing were taken and, after review by the committee, the contract was awarded to the firm of Allen & Butler. By August 4, the work was nearing completion, and the CC’s portion of the bill was approved for $165: “$140 – to be paid when work is properly connected. $25 – when contract is completed including cess pool.” The BOS had paid their portion – $150 – the previous day.34,69 Therefore, the CKDH was original construction on the lot that the CKD had previously purchased and was funded by the CC and BOS. The project had taken about four months from plans to cess pool. The move-in date is not exactly known but likely occurred shortly after completion. The CKDH was listed in a compilation of Mississippi hospitals established between 1890 and 1920. It was recorded as having 10 beds, which appears to be the original number of beds in 1908.2 On October 5, 1909, the CC approved $150 for an addition to the CKDH.34 The following year a photograph of the CKDH was taken and subsequently published in 1912.49 (FIGURE 6) This item is the earliest known photograph of the CKDH and included the most recent addition which was most likely related to the west wing. The picture reveals a wooden structure elevated on brick pillars with what appears to be a cornerstone in the farthest brick pillar on the right.

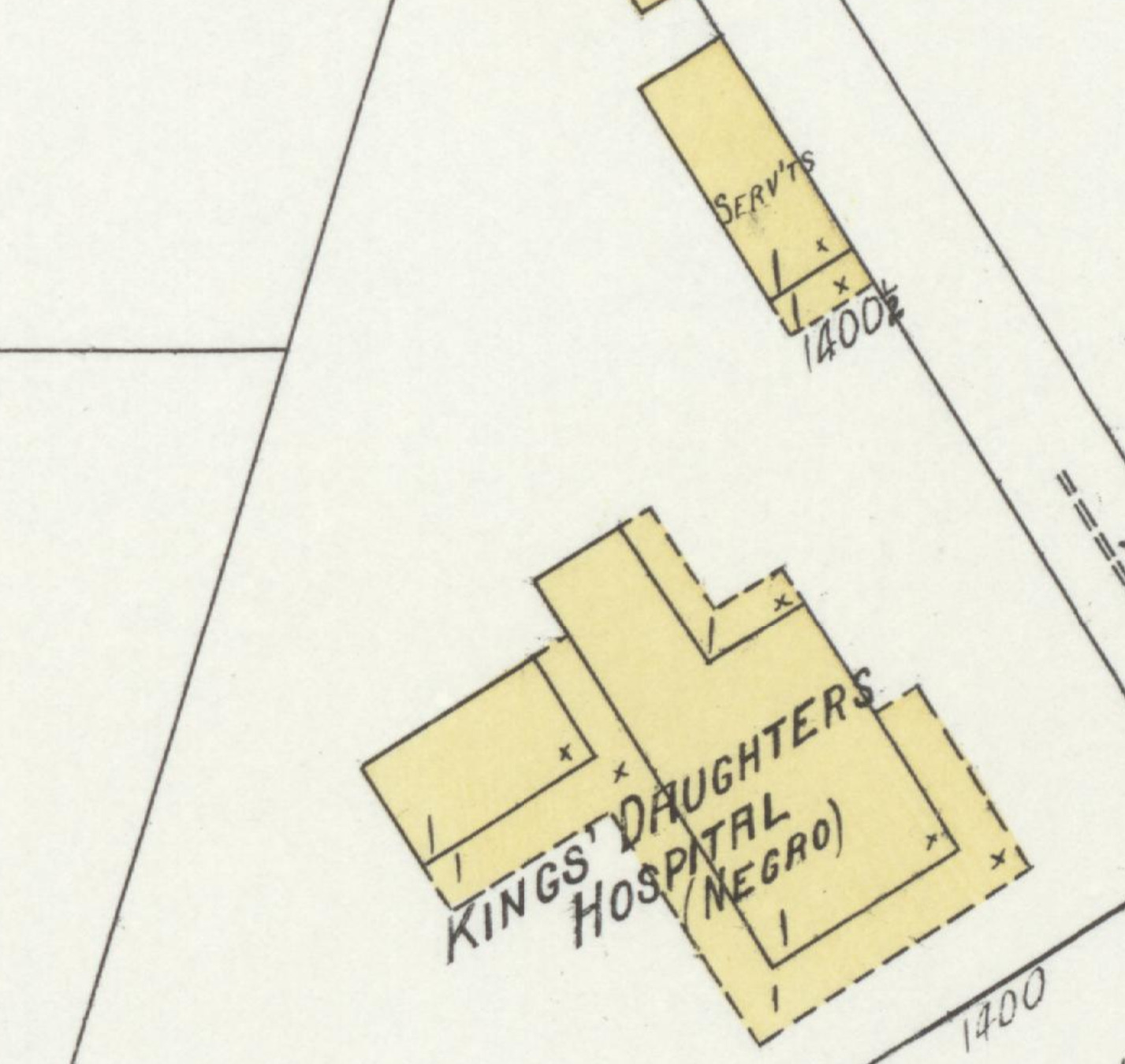

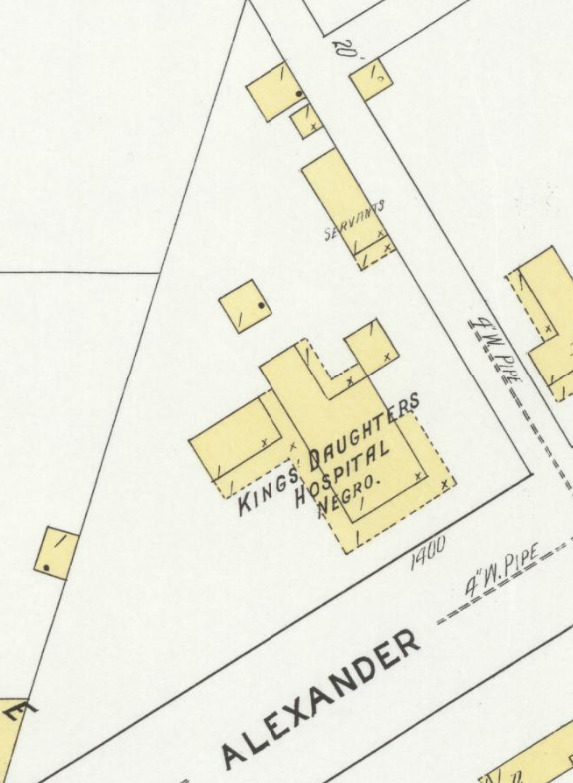

On February 7, 1911, in response to a request from KDC2 for payment relief for sidewalks in front of the white KDH, the CC agreed to pay for sidewalks in front of both the white KDH and the CKDH if the BOS agreed to pay half. One month later the BOS agreed.34 In July 1911, the CKDH appears on a Sanborn Fire Insurance Map for the first time.70 (FIGURE 7) On September 4, 1911, the CKD petitioned the CC for assistance in building a new OR. The CKD paid $200, and local government matched it. The BOS appropriated $100, and, upon recommendation of the City Physician, the CC appropriated $100.71

The CC financial report of October 1 was divided into two funds: corporate and school. The corporate fund was divided into receipts ($129,309.82) and disbursements ($134,866.05), yielding a deficit ($5556.23) for the fiscal year. Under disbursements was $2173.39 (1.7% of total disbursements and 1.6% of total receipts) disbursed under the heading of “Paupers.” Subheadings included: “Donations to hospitals – 1560.00; Sidewalks in front of property – 143.64; Insurance on colored King’s Daughters – 52.50; Medicines – 133.45; Burials – 199.00; Transportation of paupers – 84.80.”72 At that time, the CC monthly allowances were $100 for the white KDH and $30 for the CKDH.73 Not enough detail is given to stratify the exact CC contribution to indigent care, but a closer look realizes that these amounts include indigent care at both the white KDH and the CKDH to a degree. It is unclear if sidewalk funding, medicines, burials, and transportation include one or both hospitals.

Another event occurred in 1911 that would have future ramifications. Paul Gaston Gamble, M.D., arrived in Greenville and joined his brother in practice. He had completed his education and training at Vanderbilt, University of Texas Medical Department in Galveston, Tulane, Touro Infirmary in New Orleans (where he also trained under Rudolph Matas), and the New York Post-Graduate Medical School and Hospital. Paul Gamble would also remain in Greenville for the remainder of his life and was included in the family tradition of leadership in organized medicine in the state, serving as President of the Mississippi State Medical Association (MSMA), 1947-1948. In 1915, they formed the Gamble Brothers Clinic (GBC).47,63,64 The GBC would eventually become a multi-specialty clinic, evolve through name changes (Gamble Brothers and Montgomery Clinic, Gamble Brothers and Archer Clinic), and play a major role in the longevity of the CKDH.

Over the next two decades, a number of nurses assumed the leadership role of superintendent, with some residing at the facility. In 1913, Mary Hayes was at the helm, and the KDC4 advertised for “Colored Patrons of the Delta section. Competent Graduate and non graduate (sic) Nurses in charge at all hours.”74 (FIGURE 8) The CKD were continuing to improve the object of their mission which had remained consistent since the turn of the century. However, there were detractors to their efforts. In 1914, one such experience became public. At the November 4 CC meeting, a complaint had been lodged against the CKD for “indifferent management” of the CKDH. Drs. Smythe and O. W. Stone, health officers of the city and county, respectively, were tasked with recommending necessary management changes. Compliance with their forthcoming recommendations was mandatory under penalty of monthly allowance withdrawal.71 The details of changes that were implemented, if any, were not found in the historical record. Whatever they were, progress was not impeded, and the CKDH continued its mission. In 1916, Bertha Jones was the live-in superintendent.75

An important factor influencing quality of care at the CKDH was the association with Hugh Gamble, and through him, the American College of Surgeons (ACS). Gamble was an Original Fellow of the ACS in 1913. Additionally, he was a member of several other prominent professional societies, was MSMA President in 1929-1930 (starting a family tradition of leadership in organized medicine in the state), and was in the Founders Group of the American Board of Surgery in 1937. He was clearly dedicated to lifelong learning and quality care, and these professional relationships and influences undoubtedly impacted the quality of care of his patients at both the white KDH and the CKDH. He published 41 clinical articles in professional journals between 1910 and 1953.64 A review of all 41 published articles revealed that the reports and analyses of his clinical experiences utilized patient data, results, and outcomes from both hospitals, usually combined.76 He presented his work at national and regional professional venues and helped generate new information.

Prior to 1908, there is documentation for both white and black physicians treating patients at the CKD Home. After the CKDH opened, it is possible that black physicians treated patients there, but their presence is not documented in the historical record. An explanation for their absence that has been postulated is the amount of indigent care and the inability of the black physicians’ practices to absorb the costs.47,77

Much of the development of the physical structure of the CKDH occurred between 1911 and 1925. Following the first appearance of the CKDH on the 1911 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map for Greenville, there were subsequent appearances in 1915 and 1925. Compared to 1911, there was an out-building behind the hospital and a right rear addition, possibly a sun porch, by 1915.78 (FIGURE 9)

The year 1920 brought changes in the lives of many and to society as a whole – Prohibition began, the Spanish influenza pandemic ended, and American women obtained the right to vote. In February 1920, conditions at the CKDH reached a low when quality issues again surfaced. The CC appointed two councilmen to work with a committee appointed by the BOS to “investigate the condition of the Colored Kings Daughters in reference to management and financial conditions.”79 This committee appears to be an oversight committee. The BOS appointed a non-physician, George F. Archer, to represent them in a conference “with the City and the Red Cross authorities to investigate the condition of the Colored Kings Daughters Hospital in Greenville.”80 In July, the CC added Drs. Payne, Smythe, and Hirsch to the committee with the charge to “take charge of the books and superintend and collect the accounts.”79 In August, a petition was brought before the BOS by prominent citizen Joseph Weinberg and others regarding the “un-sanitary and financial condition of the colored Kings Daughters Hospital.” There was a deficit of $877.20 at the CKDH, and the BOS and CC each paid half to help turn the situation around. Also, the monthly allowance was temporarily increased to $150 with the CC and BOS each paying half. In August, Drs. Gamble and Cameron Montgomery were appointed to join the committee appointed by the CC and the BOS “to take charge of the books, superintend and collect the accounts of the colored Kings Daughters.”81 This is the first time Gamble is documented in association with the CKDH, although he had likely been treating patients there. In September, Drs. A. J. Ware and D. C. Montgomery were appointed by the CC to the “committee for the supervision of the Colored Kings Daughters.”79 There was no discussion recorded that reflected closing the hospital. Rather, the necessary means were found and allocated to continue. Things appear to have improved, and in April 1922, the state pledged an appropriation for the CKDH “provided the Colored Kings Daughters will contract the said property to seven trustees, for a period, so long as the State will make said appropriation.” The BOS appointed two of the trustees, Ware and Lizzie Green, a practical nurse in her mid-30’s who did private duty nursing, for four-year terms. The BOS believed that “the change is for the best for the colored people of Washington County.”81,82 After a strong start in the 1910’s with the CKD in control, it seems things began to decline somewhat in the 1920’s. Financial issues and management appear to be major causal factors. It may be that the CKD experienced a decline in membership, activity, and leadership for a variety of reasons. Those who played major roles in establishing the CKDH may have died, relocated, or moved on to different phases of their lives, and a succession plan may not have been well-prepared. It appears that, at this point, local government and prominent white physicians, recognizing the importance of and need for the CKDH, took the necessary steps to continue its viability.

On August 13, 1923, the BOS reaffirmed their ownership of the property on which the CKDH stood, stating that it “is to the interest of Washington County and said colored Kings Daughters Hospital that said property be conveyed to Trustees to control same.” This juncture was the first time the facility was officially referred to as the “colored Kings Daughters Hospital.” The BOS named C. C. Dean, President of the BOS; J. Allen Hunt, Mayor of Greenville; and A. J. Ware, Health Officer of Washington County, as Trustees to hold the title to the property to be used “only as a hospital for negroes.” The Trustees had full power to control the property and could mortgage it to obtain funds for repairs and improvements but could not convey it to anyone. If the property were to cease being used as the CKDH, it would revert back to the county. The next day the Trustees used the title as collateral to repay a $4000 debt to H. N. Alexander & Sons for repairs and improvements to the CKDH.83 A payment plan of $200/month for 20 months was instituted and paid in full on June 1, 1925.84

By 1925, an entire wing had been added.85,86 (FIGURE 10) This appears to be the final structure of the physical plant. A fire reportedly occurred on February 25, 1916, from a room heater. The extent of the damage is unknown, but the repairs and/or replacements involved may well explain the 1925 appearance.85,87

The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, which occurred in April, was one of the worst flooding disasters in United States history. Its impact on Greenville has been well chronicled by scholars and researchers, including Greenville historian Princella Nowell as well as author John M. Barry in his book Rising Tide.88,89 The white KDH received flood waters in its basement and lobby. This did not interfere with the rest of the hospital, and it continued to function relatively well throughout the ordeal.13 Not surprisingly, information in the historical record on the CKDH during the disaster is scant. It is known that water did invade the facility and required post-flood cleanup, involving the Washington County Health Dept.90 It is not known how the patients were evacuated, where they went, or impact on the staff. By July 4, the water in Greenville had been drained, and a celebratory parade was held.88 (FIGURE 11)

The information on the death of James Gooden provides insight regarding the CKDH in the aftermath of the flood. In his book, Barry details Gooden’s shooting by policeman James Mosely and subsequent death on July 7, 1927. Mosely and his partner, Pat Simmons, had been tasked with gathering a work crew and came upon Gooden on his porch. Mosely ordered Gooden onto the truck, but Gooden refused, having worked all night. Mosely repeated the order at gunpoint, Gooden grabbed the gun and was shot by Mosely. Further, Barry states that “blacks” carried Gooden to the “hospital” where “In an effort to save his life, two white doctors amputated his arm.” Gooden died. Barry references his account of Gooden’s care to the CC minutes from September 6, 1927.89 After a detailed search of the records held at the Greenville City Clerk’s office in 2023, the City Clerk confirmed that CC minutes between 1922 and 1930 are lost, whereabouts unknown, and that CC minutes would not be located elsewhere. Nonetheless, the account in the newspaper on July 8, 1927, provides different details. Mosley stated that he and Simmons were gathering labor for the Red Cross. Gooden refused to come when requested from his front yard so Mosley attempted to escort him to the car. Gooden grabbed for Mosley’s gun and attempted to get away, and Mosley fired two shots. Gooden sustained an abdominal gunshot wound (GSW), with the entrance wound just below the navel, around 5 PM. Simmons took Gooden to the CKDH, and Gamble was called. Gooden died around 8 PM.91 It is not known if Gooden was operated on by Gamble and if so, what operation took place, or if Gooden was in extremis on arrival, precluding operative intervention. As Gooden was a black laborer and Mosley (Mosely) was a white policeman, the incident worsened the already heightened racial tensions. The policeman was arrested, charged with murder, and never indicted.89,91

The newspaper account revealed that the CKDH was open and operable about 2½ months after the levee broke at Mound Bayou on April 21. Once the water drained, the CKDH would have been cleaned and reopened, attesting to the need for the CKDH. The details of Gooden’s penetrating trauma – arm, abdomen, or both – and its treatment remain a mystery. Whatever the truth about the altercation between Mosley (Mosely) and Gooden, the latter account of Gooden being treated at the CKDH under Gamble appears most accurate.

The 1927 Flood would change the course and trajectory of the CKDH and flip the concept of “ownership and control.”

Transitional and Middle Years: 1928-1937

Following the post-flood cleanup and reopening, white citizens of Greenville requested a change in operation and management of the CKDH away from KDC4. The issue was brought before the BOS, and although their mission would remain the same, KDC4 agreed to a committee which would operate the hospital. The committee was composed of representatives appointed by the CC (Greenville Mayor E. G. Ham), BOS (Dr. H. P. Rankin, Director of the Washington County Health Dept.), and KDC4 (E. D. Davis, owner of Davis Drug Co., member of the BOS, and planter). The committee was created on March 5, 1928. Rankin served about a month and was replaced by J. A. Lake who resigned in October. That position was vacant for nearly five years until August 1933 when F. A. England was appointed. His tenure was short before being replaced by F. G. Millette.92–96

The committee was known as the Board of Control (usually) or the Colored King’s Daughters Committee (occasionally). Specifically, the Board of Control was to manage “both the realty and equipment . . . with full power in said Board of control to manage said hospital in such manner as they may deem fit and proper for the best interest of the colored people of Greenville and Washington County. To this end said Board of control may prescribe rules for the admission of patients and the conduct of the same while in the hospital; fix, and collect charges to be made for all services rendered by said hospital, employ necessary help for the conduct of the business of said hospital and prescribe rules for the goverment (sic) of the help so employed, fix the pay of any and all employees and do any and all things necessary to the conduct of said Hospital.”96

On February 1, 1929, it had been nearly two years since the 1927 Flood. A report on the CKDH from March 22, 1928, to February 1, 1929, was prepared by Davis and Ham of the Board of Control and submitted to the BOS on March 4. A total of 480 patients had been admitted, of which 101 were charity patients (21%). Deposits were $10,959.10, and disbursements were $10,671.94, leaving a balance of $287.16. The following improvements were made: “spent approximately $2500 in repairing and painting Main Hospital Buildings, bricked buildings from ground up, painted inside and out, and rebuilt servant’s house, spent about $250 in repairing the three furnaces which were badly damaged by flood, and had never been put in condition, All beds have been re-enameled and conditioned, supplied with new mattresses, making them practically new, and shades hung to all windows, Have bought two dozen blankets, 150 sheets, 150 pillow slips, necessary towels, dishes, kitchen range, and cooking utensils, also covered flooring of operating room, and kitchen with inlaid Linoleum, Plumbing was found to be in a very bad condition, and same has been entirely gone over and necessary repairs made, Have installed Frigidaire, and equipment, Efficient nurses have been engaged, and salaries of all employees increased, and paid, as we thought advisable.” The BOS was grateful and commended the Board of Control for the “careful and painstaking manner in which they have reconstructed the financial policy and the general rehabilitation of the Home” and for their “untiring efforts for the general good they have performed for the community for which they receive no enumeration (sic) whatever.”96

As previously mentioned, the CKDH required cleanup after the flood and appeared to be functional by July 7, 1927. The details of the cleanup and reopening are unknown, and it is possible that the CKDH operated in a limited capacity following the cleanup. The magnitude of the 1928-1929 renovations detailed above suggest that major repairs/renovations were not undertaken in the immediate post-flood period. The completion of the renovations before the stock market crash in October and the onset of The Great Depression was serendipitous. Importantly, the work appears to have been funded from the local government without controversy, underscoring the importance of the CKDH to the city and county. This is even more significant with the realization of the near certainty that no insurance coverage was involved. Private flood insurance was available in the early 20th century, but the 1927 Flood effectively ended that industry. The National Flood Insurance Program would not begin until 1968. It is all but certain that the CKDH did not have the benefit of private flood insurance.97–99 Amazingly, the CKDH survived the disaster.

Into this newly rehabilitated facility came some of the earliest black professional nurses in the state. Present since at least 1928, Anne M. Fridge is first seen listed in a city directory in 1929.50,85,100 The listing has a “(c)” after her name, signifying “colored” and states she is “supt. Kings Daughters Hospital (c).” Her residence is listed at the 1406 Alexander St. address of the CKDH.100 In the 1930 U. S. Census, an interesting snapshot of the CKDH is revealed. On April 15, 1930, the inhabitants of the “Negro Kings Daughters Hospital” are listed as:

Rent was $5/month.101 It appears that all were residents of the facility, likely in both the main building and the outbuildings. Annie Fridge had received her training at Grady Hospital in Atlanta according to her colleagues.85 In the 1920’s, Fridge would have been at the Training School for Colored Nurses at Grady Hospital in Atlanta.102,103 Fridge was a native Mississippian according to the 1930 U. S. Census information, but her pathway to Atlanta and then Greenville is unknown.101 She remained in her position until at least 1931.104 She subsequently married and left the area.105

Lela Jones (Graves) was the night shift supervisor opposite Fridge.50,85 She received her nursing training at Matty Hersee Hospital in Meridian. She was recruited by A. J. Ware and arrived at the CKDH in 1928. She stayed two years and then left because of the impact of night duty on her social life.50 Gertha McMullen (Bridges) came to the CKDH in 1929 and would stay until it closed in 1953. She also received her nursing training at Matty Hersee Hospital.85 In 1931, McMullen took over as Supt. following the departure of Fridge.106 She would either remain in the position, or there was a short period of vacancy in the position until the arrival of Oris Hemphill (Doolittle) in 1934. Hemphill had received her nursing training at Matty Hersee Hospital and followed this training with post-graduate work in Memphis and CHNO. The CKDH was her first job, and she married Greenville policeman Robert Doolittle in 1937. She remained at the CKDH until transitioning to the new Washington County General Hospital (WCGH) in 1953.107–109

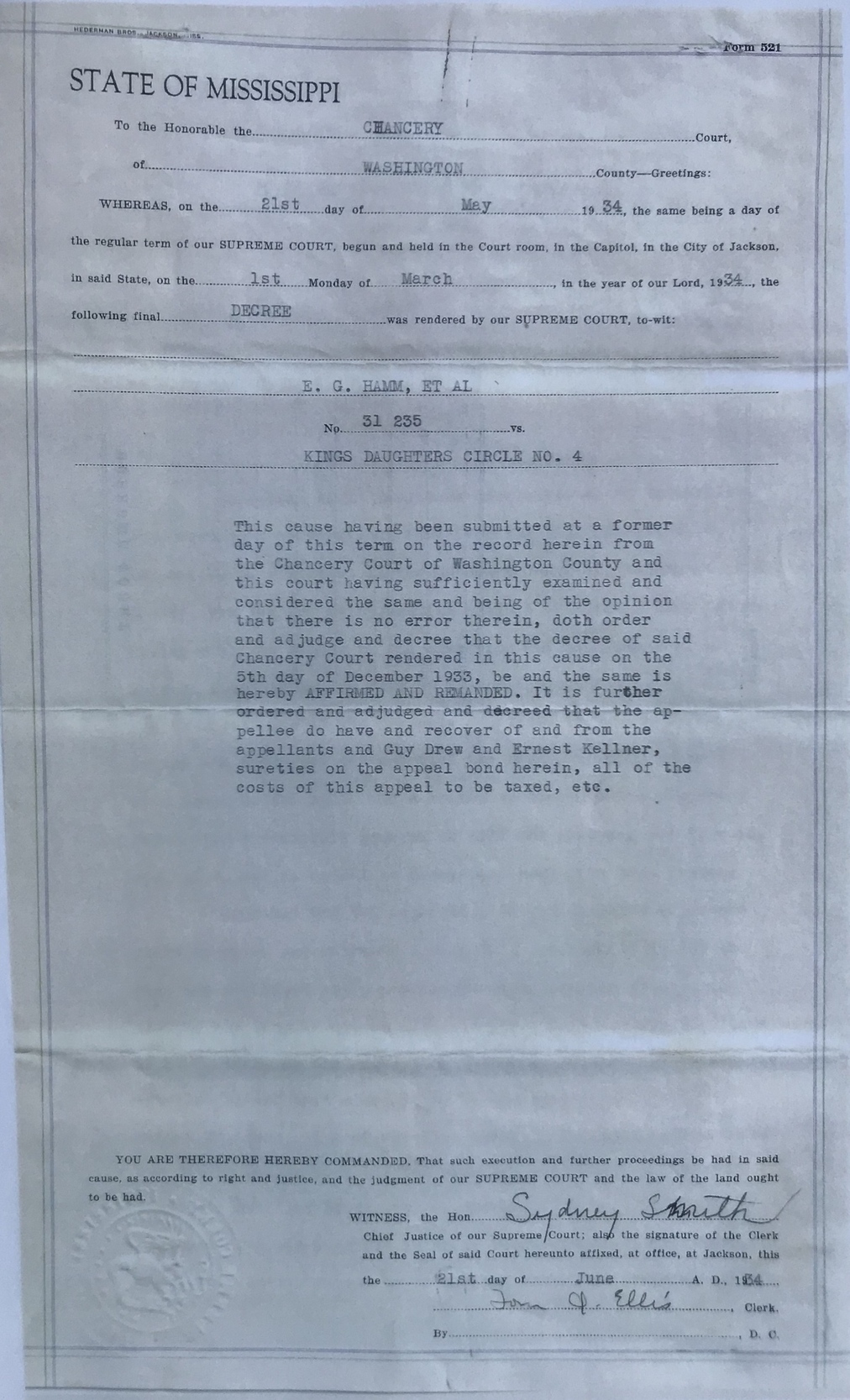

The Board of Control operated the CKDH until June 1933. At that time, dissatisfied with the management of the CKDH, KDC4 discharged their representative, E. D. Davis. KDC4 was planning to move in a different direction and organized a leasing agreement with Drs. Ware and Gamble to operate the CKDH.92 The BOS filed suit against KDC4 claiming title to the property, but the suit was dismissed.92,93,95,110,111 F. G. Millette was then appointed by the BOS as their representative to operate and manage the CKDH over the protest of KDC4.92,93,112 When KDC4 demanded that Ham and Millette discontinue, they refused. Millette stated that they would continue unless enjoined by a court. Thereafter, KDC4 obtained an injunction on December 4, 1933, against Ham and Millette from operating the CKDH as their acts and conduct constituted a “continuing trespass.” Gamble and Ware were sureties for the $500 bond for KDC4. Ham and Millette then filed a demurrer and a motion to dissolve the injunction which was overruled the next day in Chancery Court of Washington County. Ham and Millette appealed to the Mississippi Supreme Court. The appeal was heard in Jackson on March 5, 1934, and the Chancery Court’s decree in favor of KDC4 was affirmed and remanded. (FIGURE 12) Ham and Millette surrendered possession and management of the CKDH. Both sides, through their attorneys, H. P. Farish for KDC4 and Ernest Kellner for Ham and Millette, agreed to a final decree on March 20, 1935. In this final decree, Ham and Millette were enjoined from operating the CKDH, and the cash balance of $289.77 and all property were turned over to KDC4. The petition of Greenville and Washington County to intervene in the cause was denied.92,93

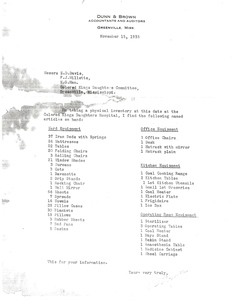

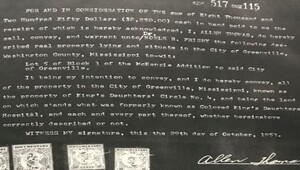

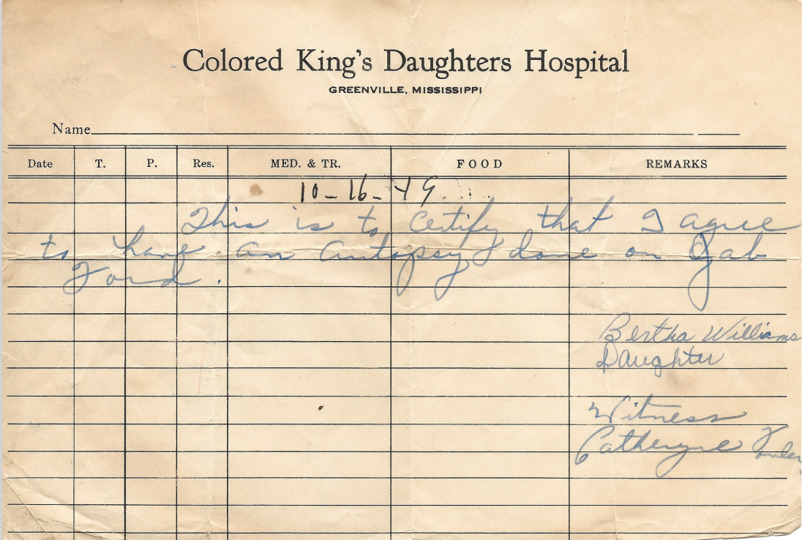

This experiment in hospital administration by politicians and businessmen with no medical background was over for the CKDH. It is not known how active the BOS appointees to the Board of Control – Rankin, Lake, and England – had been prior to Millette. Ham and Davis, throughout their tenure operating the CKDH, had a great interest in the venture – planning weekly menus, stocking the dietary department, soliciting material donations, and keeping relatively detailed records.94,112 (FIGURE 13) It is unknown whether Ham and Davis received any financial compensation for their services to the CKDH, either directly or indirectly.

After the Supreme Court decision, KDC4 appears to have faded significantly in the historical record from their level of activity in years past. As previously mentioned, by 1931, no “colored Circles” were known by the Mississippi Branch of the IOKDS.14 The reason for KDC4’s demise is unknown, and it is difficult to trace. Throughout the historical record, except for the very early years where individual names were published, the group is referred to collectively as the “Colored King’s Daughters” initially and later as “King’s Daughters Circle No. 4”. The lack of individual names makes meaningful identification essentially non-feasible.

In 1935, Alabama beat Stanford in the Rose Bowl, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act into law, Hoover Dam was completed, and Senator Huey P. Long of Louisiana was shot and subsequently died. Moving forward after the state Supreme Court decision, Gamble and the resources of the GBC would be the primary driving force behind the CKDH.

With Gamble and his colleagues in operational control of the CKDH, it is important to consider hospital standardization and regulation, or lack thereof, with regard to the CKDH. Hospital standardization and approval was pioneered by the ACS. After several years of organization, preparation, and development of standards (1911-1918), the ACS initiated its Hospital Standardization Program in April 1918. The first printed list of approvals appeared in 1921. Listings were by state and published nearly annually until 1953. Following World War II, the ACS desired to divest itself of the program for financial reasons. A Board of Commissioners was developed from representatives of the ACS, American College of Physicians, American Medical Association, American Hospital Association, and the Canadian Medical Association, and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals (JCAH) was formed. The program was officially handed over to the JCAH on December 6, 1952.113 JCAH later became the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) and continues today as The Joint Commission.

In 1922, the first facility approved by the ACS Hospital Standardization Program in Mississippi was Matty Hersee Hospital in Meridian. The number of approved hospitals listed steadily increased. The most listings was 27 in 1933, 1934, 1935, and 1940 – 1941. The white KDH first appeared on the list in 1925 and was on every list published through 1952. Their listing read “Kings Daughters Hospital, (white) Greenville” or “King’s Daughters’ Hospital (White)” until 1936 when it became listed as “King’s Daughters’ Hospital.” This clearly implied the existence of a facility for black patients through 1935 – an unlisted “King’s Daughters Hospital, (colored)” – in Greenville. And that was the case. Among the Mississippi listings, the white KDH was the only hospital with the racial designation. There was no other facility listed with the designation “colored” or “black.”114,115 The CKDH does not appear to have met the minimum standard of the ACS approval program published in 1924, nor any other black hospital in the state during those years, as none were listed. This absence is readily attributed to size, support services lacking, and strict racial boundaries. It is unlikely that applications from those hospitals were even made to the program.

On the state level, there was simply no significant regulatory or accrediting agency or program until 1936. In 1936, the Mississippi State Hospital Association (H. A. Gamble, President), in conjunction with MSMA, sponsored, supported, and was instrumental in obtaining the passage of Senate Bill No. 223 in the regular session of the state legislature. The bill addressed 3 issues: (1) funding care of the indigent sick (2) maintenance of higher standards of hospitals and hospitalization, including nursing practice (3) development of a plan of hospital insurance applicable to rural conditions. This legislation would be administered through the formation of a State Hospital Commission.116 It has been suggested that the Commission was simply inert.7 Regardless, there was no national or state regulation of the CKDH. Quality of care was a direct reflection and result of the physicians and staff who worked there and the charitable efforts that helped support and sustain it.

In 1933, the CKDH was listed in a comprehensive reference book of American and Canadian hospitals. It was noted to have 40 beds, owned by the IOKDS, and as of calendar year 1931, had admitted 425 patients with an average daily census of 12. Superintendent was Anna May Fridge.104 Ownership was incorrect and was clearly inferred from the name. The 1937 edition of the same publication gave more detailed information. “A. J. Ware, M.D. and H. A Gamble, M.D.” were listed under “Ownership and control”. It had 60 beds and for the year ended August 31, 1936, had admitted 750 patients with a daily average census of 50. There were 12 births, and total hospital days was 18,250. The nursing service director was Oris Hemphill, RN, who had arrived in 1934. Also noteworthy was financial data: “Current value grounds, buildings, and equipment, $5000. Endowment, $12,000. Income from city and state, $12,720.”117

It is worthwhile to look at the information for Mississippi in 1937 in this publication. There were 76 hospitals listed. “Colored admitted” was listed in the descriptive information of 41 of these. One, a Veterans’ Administration facility, stated “colored not admitted.” There were 3 that carried the designation “colored” in their name, and all 3 were located in the Delta: Clarksdale (Afro-American Colored Hospital, 12 beds); Greenwood (Greenwood Colored Hospital, 12 beds); and Greenville (CKDH, 60 beds).117 The Afro-American Sons and Daughters Hospital was not listed but was fully operational during this time.6 There was one hospital for Native Americans (“Indians”) and 15 government hospitals – 12 state and 3 federal.117

It is not completely surprising that links to renowned individuals have been associated with the CKDH. It is of interest to explore these linkages to delineate fact and myth. (FIGURE 14) The friendship between Gamble and Dr. Will Mayo has been well-documented. The two surgeons would visit during stops in Greenville while Mayo was traveling up or down the Mississippi River between Minnesota and the Gulf of Mexico aboard his yacht, the North Star.64 It has been postulated that Mayo visited the CKDH in addition to the white KDH because of a 1931 entry in the North Star’s logbook which reads, “The men called on Dr. Gamble and visited hospitals and clinics.”118 The Mayo visits to Greenville occurred between 1927 and 1931. These visits were typically documented in the local newspaper as well as by Mayo once he returned to Rochester, MN.119–121 The lawsuit and subsequent leasing arrangement had not yet placed Gamble in a position of oversight and leadership at the CKDH, but he was treating patients there. The major renovations at the CKDH had been completed in 1928-1929. Although not documented, it is possible (and speculative) that Mayo may have visited the CKDH briefly during a Gamble-led tour of Greenville. This most likely would have been after completion of the 1928-1929 renovations.

Another association that has received attention is the perception of the CKDH by famed Civil War historian, author, and Greenville native Shelby Foote. During the summer of 1936, the 19-year-old Foote returned to Greenville following his freshman year at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill. His 1.9 GPA may have had an impact on the young man’s state of mind that summer. His friend and fellow UNC student, future physician and author Walker Percy, returned home to Greenville as well. Percy worked at the GBC that summer under pathologist E. T. White while Foote worked at U. S. Gypsum Company and helped out at the Percy’s 3343-acre Trail Lake Plantation. He developed friendships among the plantation workers and witnessed a friend’s stabbing, which required hospitalization but was apparently not life-threatening. The following day Foote made his first visit to the CKDH to bring his friend cigarettes. His expectations are unknown, but his impression was that it was crowded with few doctors and nurses, and he interpreted this as lacking in medical attention. Foote biographer C. Stuart Chapman states that Foote remembered the episode as one of the “experiences about race that hit me hard. I couldn’t believe what I saw. That was one of the first shocks I had in terms of what was done to blacks.” Foote’s one-time experience is certainly open to his interpretation. Another interpretation could be the naïve view of a young man unfamiliar with healthcare perhaps debating apathy, indifference, and his future within himself. His unfamiliarity with illness and healthcare, or perhaps immature insensitivity, was illustrated that summer when Foote tended to laugh at the expressive aphasia of Will Percy, Walker’s uncle, following a stroke.122,123

Another consideration for Foote being “viscerally disgusted” during his brief visit to the CKDH may have been due to the smell within the hospital. Unfamiliar odors can readily elicit a visceral response. This issue surfaced during the course of research for this article from individuals who had either worked there or had family members hospitalized there. It was never characterized or described as unsanitary, unclean, or non-hygienic. Rather, it was described as “normal hospital smell but exaggerated” and possibly a strong disinfectant smell. It was also attributed to patient conditions such as burns.124,125 This would tend to reinforce the reality of limited resources and “doing the best with what they had,” and would not suggest purposeful neglect.

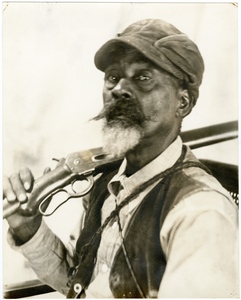

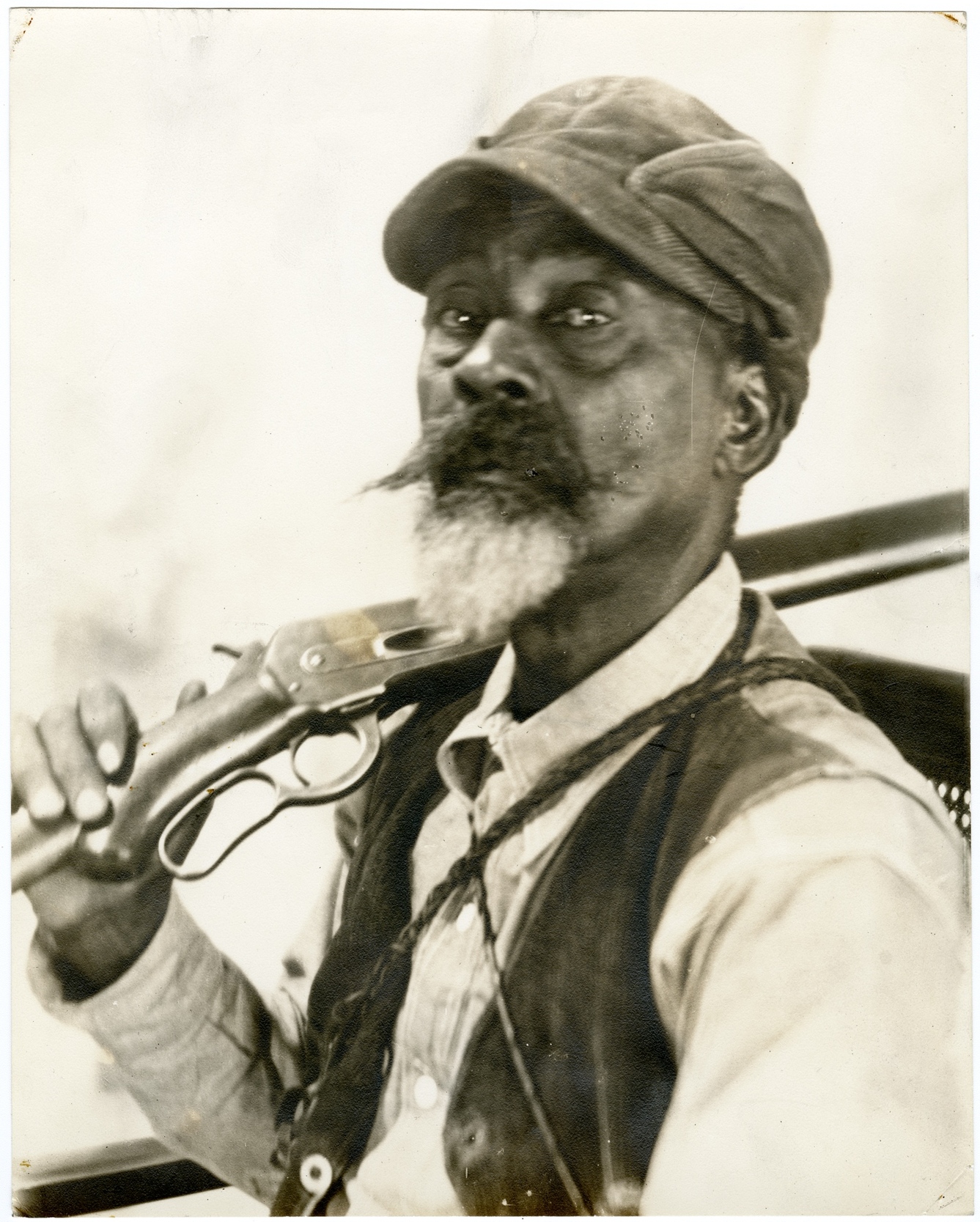

One of Greenville’s most well-known historical figures is Holt Collier. Born into slavery about 1846, Collier was a Confederate veteran and a renowned hunting guide who led hunts with President Theodore Roosevelt, including the famous “Teddy Bear” hunt of 1902 in the Mississippi Delta. His story is detailed in the excellent 2002 biography by Minor Buchanan, Holt Collier: His Life, His Roosevelt Hunts, and The Origin of the Teddy Bear. Collier and his wife, Frances, purchased property at 304 N. Broadway in Greenville in 1908 and built the house he would live in for the rest of his life. By 1919, he was completely retired from hunting and adjusted to being somewhat of a local celebrity. As he aged, Collier was characterized as losing his eyesight and finally becoming feeble. It would seem intuitive and likely that had Collier required hospitalization or surgery during his later years, he would have been in the CKDH. He would have been its most famous patient. A brief biography of Collier written shortly after his death states that he was “in the hospital where he spent the last week or ten days of his life.”126 The “hospital” was the Sarah Williams Nursing Home (SWNH) which was located at 507 N. Broadway, just a few blocks from Collier’s home.

Sarah Williams was born around 1893 in Mississippi, and by 1913, she was working as a nurse for Dr. J. H. Miller at Miller’s Infirmary. She also gave the address of the facility as her home address.127 These proprietary hospitals were not uncommon for black physicians to operate given the limitations imposed by race.77 (FIGURE 15) It is important to remember that the Miller Infirmary would have been in direct economic competition with the CKDH at that time. Miller was the brother of Yazoo City physician and surgeon L. T. Miller. Their relationship and association have been chronicled previously.6 Williams continued working there until at least 1916.128 She may have received nursing training at the AAS&D Hospital in Yazoo City or Jane Terrell Hospital in Memphis.129–131 By 1929, she was widowed and living at 507 N. Broadway. This location was the permanent address of the SWNH. At the time, she was 37 years old and living with and renting from Mary Calhoun at the N. Broadway address in the 1930 census. Both women are listed as “practical nurses,” “working,” and “single.”132,133 A next door neighbor was 12-year-old Fannie Murray, a future SWNH nurse.134A few doors away was Opal Kage, age 22, who was a “hospital nurse”, and may also have worked at the CKDH, the SWNH, or both.133 This information illustrates the impact of these two hospitals on the surrounding areas and neighborhoods for employment opportunities. It is unknown exactly when the SWNH opened, but likely it was around 1930. In 1931, Mary V. Calhoun is listed in the city directory as superintendent of the SWNH at the N. Broadway address.106 Calhoun had previously worked at the CKDH.51

The SWNH followed a similar dynamic to that of the CKDH and the GBC with a mutually beneficial leasing arrangement. The facility was a renovated four-room house operated by nurse Sarah Williams in conjunction with a group of white physicians – Drs. A. G. Payne, Jerome B. Hirsch, Sr., Otis H. Beck, (and later) George W. Eubanks, and Jerome B. Hirsch, Jr. Black physicians – Drs. S. N. Sisson, Charles E. Holmes, and Leonadis DeLaine – also treated patients there during its early years. Care available there included surgical procedures and deliveries. In addition to having local celebrity Collier as a patient, Dr. T. R. M. Howard, during his time in Mound Bayou (1942-1953), was reported to have operated at the SWNH on occasion.50,85,126,135–138 These physicians, generally speaking, were in economic competition with GBC physicians, and it is probable and reasonable that the SWNH evolved as a result of the business arrangement between Gamble and the CKDH which enabled monopolization of the CKDH, primarily the single small OR for which there was a high demand.

Like the white KDH and the CKDH, the SWNH received an allowance from the BOS, albeit a smaller amount.139,140 The physicians utilizing the SWNH had relationships with local industry to care for their workers. The SWNH also generated revenue from “Government patients”.50 These were workers and their families who were employed on Works Progress Administration (WPA) projects in Greenville from 1933 to 1940. These projects included construction of a National Guard armory, an elementary school, and the U. S. Highway 82 bridge across the Mississippi River between Greenville and Lake Village, AR; improvements to the high school athletic field, Mississippi River levee, and the water works and sewage disposal; and completion of gravel roads throughout the county.141 Once the WPA funding ended, it created a financial hardship for the SWNH and contributed to its eventual closing.50

Beck was listed as a director or superintendent in the 1936 city directory.142 In 1938, Bessie Bell lived next door to the SWNH and served as superintendent.143 In 1940, Beck’s wife, Ethel, functioned as the director.144 In 1946, Carrie Johnson was superintendent and also resided at the facility.145 Not surprisingly, there was some crossover between the nursing staffs of the CKDH and the SWNH (Lela Jones Graves and Mary Calhoun, among others).The 17-bed hospital would keep functioning until its services were no longer needed as its funding sources faded, and its story became history. It likely closed after the CKDH. Once these facilities were closed, the nursing staffs had employment opportunities at the new WCGH or the private offices of the physicians with whom they had formed professional relationships with at the CKDH and the SWNH (Gertha Bridges, Oris Doolittle, Fannie Mae Murray, and Lillie Mae Shanklin, among others).51,71,85,134,135,146

Holt Collier died on August 1, 1936, at age 90, at the SWNH in Greenville after being moved from his home when he was no longer able to stay there.136,147 He was pronounced by Otis Beck, and cause of death on the death certificate was listed as myocardial insufficiency with bronchopneumonia contributing.136,147,148 Nothing has been found in the historical record to indicate that he was ever hospitalized at the CKDH.

Zenith and Evolution to Progress: 1938-1953

Throughout its lifetime, the nursing staff of the CKDH was primarily populated with “practical nurses.” These individuals were employed as aides and assistants at the CKDH and learned their practical nursing skill set on-the-job from the RN’s and the physicians treating patients there. This was known to be a good source of employment and opportunity for black women in the surrounding neighborhoods. Twelve-hour shifts (7AM-7PM and 7PM-7AM) were typical with a half- day off per week and a full day off per month.50,51,85,105,124,125,149 Information on many of the CKDH nursing staff is unavailable in the historical record. However, research for this project has yielded the names of some of those individuals: Mary Calhoun, Addie Williams, Bertha Holmes, Alberta Finch, Rosalie Parker, Mary Britton, Dolly Charles, Pattie Ware, Effie Lowe Patton, Leary Evans, Mary Hilliard, Mary Dillingham, Mariah Johnson, and Lillie Mae Shanklin.50,51,85,105,124,149

Another perspective on the CKDH from direct experience is that of retired pathologist, Benella Oltremari, M.D. Oltremari attended nursing school at the white KDH School of Nursing from 1947-1950 and received her R.N. diploma. Following graduation, she was recruited by Gamble to be a surgical first assistant as an employee of the GBC. Her tenure was from June 1950 to July 1951. She lived halfway between the white KDH and the CKDH, had a telephone installed in her room, walked to the hospitals when called, and either worked or was on call 24/7. At the CKDH, Oltremari and the CKDH surgical nurse frequently closed the incision at the end of operations while the surgeon would proceed to the white KDH. That skill set had been taught to them by the surgeons over time. Oltremari recalled the small size of the facility, the strong “hospital smell”, how busy it was, and how many of the staff were trained on the job.125 Oltremari subsequently returned to college at Delta State University and completed medical school and residency training at the University of Mississippi Medical Center before returning to Greenville for the remainder of her career.

By its later years, the CKDH had evolved to become primarily a charity surgical hospital. Yet, throughout its lifespan, it provided care for a wide variety of conditions. The CKDH, with limited resources and additional specialty expertise added over time, successfully handled obstetrics; neonatal care and premature babies; pediatrics (including caustic esophageal stricture, tetanus, and abandoned baby); infectious diseases such as malaria, typhoid fever, meningitis outbreak, and widespread syphilis; palliative care for advanced cancer; mass casualty event (tornado); and a wide range of treatment for surgical conditions. These included blunt trauma (falls, motor vehicle accidents [MVAs]) and penetrating trauma (stabbings, GSWs), burns, abdominal surgery, amputation, breast cancer, orthopedics, ophthalmology, gynecology, head and neck surgery, and emergency neurosurgery. Successful repair of a cardiac stab wound and successful repair of a hip fracture in a 102-year-old as well as the city’s first pneumonectomy were done at the CKDH. An online search and review of “colored kings daughters hospital” in Greenville newspapers between 1905 and 1953 prominently demonstrates the large amount of trauma patients treated at the CKDH.50,85,105,108,124,146,150–158

The separation of healthcare by race in Greenville was not limited to African-Americans. Two court cases about school segregation, one well-known and one lesser-known, in the 1920’s are demonstrative of this reality. Chinese began arriving in the Mississippi Delta around 1875, became successful merchants, and grew into a sizable group as they assimilated into life in the Delta. By 1952, the population of Chinese Americans in Greenville was the second largest in the South.123,159–161 The first case, Gong Lum v. Rice, arose in 1924 when grocery store owner Jeu Gong Lum’s two daughters were not allowed to attend Rosedale Consolidated High School and were directed to the colored school as they were not white. Gong Lum sued, and the Circuit Court of Bolivar County ruled in favor of the girls. The case was appealed to the Mississippi Supreme Court where the lower court’s ruling was overturned. Gong Lum appealed to the U. S. Supreme Court which upheld the Mississippi Supreme Court in 1927. U. S. Supreme Court Justice (and former U. S. President) William Howard Taft delivered the opinion. He wrote “Most of the cases cited, it is true, over the establishment of separate schools as between white pupils and black pupils, but we cannot think that the question is any different, or that any different result can be reached, assuming the cases above cited to be rightly decided, where the issue is as between white pupils and the pupils of the yellow races. The decision is within the discretion of the state in regulating its public schools and does not conflict with the Fourteenth Amendment.”161–163

The second case, Bond v. Tij Fung, arose when Joe Tin Lun was denied admission to Dublin Consolidated High School near Rosedale. He was advised to attend the nearest colored school. The legal process began, and the Coahoma County Circuit Court agreed with the Luns. The school superintendent appealed to the Mississippi Supreme Court which considered the issue previously settled based on Gong Lum v. Rice. Therefore, they ruled in favor of the school in 1927. Associate Justice James G. McGowen wrote, “We have fully gone into that phase of this case in the recent case of Rice v. Gong Lum, where we held that, under section 207 of the Constitution of 1890, it is provided there shall be separate schools for the white and colored races; that the term “white race” is used in said section of the Constitution as limited to the Caucasian race, and the term “colored race” is used in contradistinction to “white race,” and involves all other races.”161,162,164

It is not surprising then that the Chinese population in Greenville and vicinity received care at the CKDH, given the strong precedent in education. Only two races were considered – white and non-white, or colored (all colors).156,165–168 Greenville native and prolific author David L. Cohn (1894-1960) and Greenville Pulitzer Prize winner William Hodding Carter, Jr. (1907-1972) both write about the complexity and vicissitudes of race and healthcare during this era. Cohn relates the story of a young American-born Chinese man who was prominent among the Chinese population presenting to the white KDH with severe symptoms and signs of appendicitis. He was denied admission due to its white-only policy. Ironically, the hospital had accepted monetary contributions from the Chinese as the young man’s father had previously donated $500 to the white KDH. The young man then went to the CKDH and was operated on by a white surgeon.169 Carter examined the social segregation issues faced by both the “Chinese-Chinese” and the “Negro-Chinese” and the CKDH as their primary hospital facility.160 Additionally, the CKDH was also the only hospital facility available to patients of Hispanic origin, primarily from Mexico.170