This month, I offer a poem, the third in a series, by Adele Ne Jame, a first-generation Lebanese American who has lived in Hawai’i since 1969. She has written extensively about Hawai’i and Lebanon in her poetry collections, including Field Work, The South Wind, Poems, Land and Spirit, and in her new manuscript, First Night at the Beirut Commodore and Other Poems. She has taught poetry at the university level in Hawai’i since 1986, and she has served as the Poet-in-Residence at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her work has been published in journals such as the Georgetown Review, Ploughshares, Atlanta Review, Nimrod, the Denver Quarterly, Poetry Kanto, and the Notre Dame Review. Her many awards include a National Endowment for the Arts in Poetry, a Pablo Neruda Poetry Prize, a Robinson Jeffers Tor House Prize and an Eliot Cades Award for Literature. Her poems have been exhibited as broadsides at the Sharjah/ Dubai International Biennial, UAE and at the Arab American National Museum, Dearborn, Michigan. She and her artist daughter, Melissa Chimera, served as the 2022 Mikhail Series Lecturers at the University of Toledo.

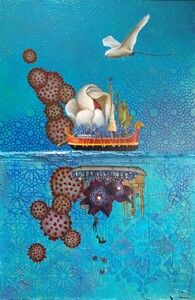

The accompanying image is Melissa Chimera’s The Promise (2020, mixed media on wood), which, according to the artist, “critiques the disjoined experiences of those with and without aid during the health and mass migration crises of recent years. Resting above the water and below a koa’e kea bird, a ship filled with medical professionals tends to a patient while those below face a precarious fate.” The poem was first published in Vita Poetica, Autumn 2023.

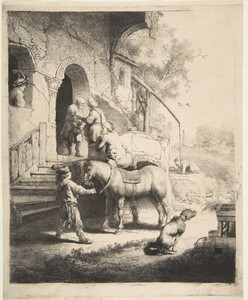

The poem below, “Rembrandt’s Good Samaritan, Then and Now,” considers two etchings, Beggar Seated on a Bank (1630) and The Good Samaritan (1633), by Dutch Baroque painter and printmaker Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669). A prolific master in three media, Rembrandt produced about three hundred paintings, three hundred etchings, and two thousand drawings. He was one of the greatest visual artists in the history of art, and arguably, the greatest etcher that ever lived. Perhaps, most importantly, Rembrandt was an expert story teller, able to craft a narrative in works on canvas and on paper. Here, inspired by the narratives of two etchings, the poet comments on the artist’s life, marked by suffering and loss; his artistic innovation; and his message of compassion and humility that is particularly relevant to today’s healthcare professionals. Rembrandt “suffered / the loss of three children,” who died shortly after birth, and he lost his beloved wife Saskia to tuberculosis after just nine years of marriage. While Rembrandt gained financial success through his artwork, he “died poor,” and like Mozart, was buried “in an unmarked grave.” Yet, he was “the master who harnessed the forces of light and dark,” perfecting the technique of chiaroscuro, and “who plunged so deeply into the mysterious” that post-impressionist painter Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) “thought him a magician.” (In his letters Van Gogh wrote that he would give up ten years of his life to sit in front of Rembrandt’s painting The Jewish Bride [1665-69] for two weeks, eating only a stale crust of bread.) The son of a miller, Rembrandt was born into humble beginnings and thus was sensitive to suffering, tolerated diversity, and deeply empathized with the human condition. He was a social outsider who associated with lowborn people, “happy in the company of workers and street people,” and “wiped his dirty brushes on his clothes / not caring a whit what others might think.” As an artist, he was a nonconformist, a revolutionary who flaunted the rules of the Academy in favor of a psychological realism. For example, Renaissance-era dignified portraits aspired to record the sitter’s social status, but in Rembrandt’s self-portraits, there is no idealization or vanity: In the self-portrait Beggar Seated on a Bank the artist is “hunched in rags” with “scruffy hair,” a man who “thought himself ugly—and preferred it to the beautiful.”

In the etching The Good Samaritan, a reproduction of his painting by the same name (1630), Rembrandt adds to the foreground a dog defecating, a note of everyday reality born of the artist’s “love of nature” which “gave us beauty / despite his dead birds / or dogs doing what dogs do.” (“Dead birds” are the subject of two of Rembrandt’s paintings from 1639, The Bittern Hunter and Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl). Rembrandt’s sense of humility and self-effacement are evident in his interpretation of the final scene in Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37). In summarizing the parable, the speaker of the poem explains that “a ransacked traveler,” attacked by robbers is ignored by passersby, including a priest, until a Samaritan, an enemy of his people, takes pity on him, “then sets him on his own animal / and leads them to an inn.” The next day, the Samaritan “pays the innkeeper / and promises to return.” Typical of his depiction of biblical characters, the figures in the etching are not distant or abstract but down-to-earth people feeling genuine emotions, and by including the defecating dog in the foreground in the biblical scene, “the artist melds the earthly and the spiritual.” In his imagining of this scene, Rembrandt reveals “the faces of all those outside the inn” but not that of the Samaritan. Instead, “his back is turned to us,” and he thus becomes “the embodiment of the injunction: Do not let your left hand know / what your right hand is doing.” In evoking these words Jesus uttered during the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 6:3-4), the speaker underscores Rembrandt’s message: it is in his humble anonymity that the compassionate Samaritan’s “radiance burns white hot.” As the poem’s title indicates, the message of the Good Samaritan is as relevant “now” as “then.” In his last public speech, a presidential inaugural address of the Classical Association of Oxford, delivered in May 1919, the iconic physician Sir William Osler (1849-1919), evoked the Hippocratic ideal of “philanthropia and philotechnia” (love of humanity and love of science) when he advised medical professionals of the importance of empathy and compassion in treating patients: “The practice of medicine is a calling in which your heart will be exercised equally with your head.” Osler argued that it was a “reasonable ambition” that respect for science be compatible with “a sense of brotherhood reaching the standard of the Good Samaritan.” Noted for his charitable life, Osler once remarked, “There was no discrimination in the charity of the Good Samaritan, who stopped not to ask the stripped and wounded man by the wayside whether it was by his own fault the ill had come; nor of his religion; nor had he the wherewithal to pay for his board.” In stressing the need to “cultivate equally well hearts and heads,” Osler warned against medicine turning into assembly-line work. Today, when physicians have become “providers” and patients “consumers,” Osler’s message and the lesson of The Good Samaritan endure.

The editorial assistance of Cathy Chance Harvey, PhD, of Tylertown, in the preparation of this poem is gratefully acknowledged. Physicians and poets are invited to submit poems for publication in the Journal either by email at drluciuslampton@gmail.com or regular mail to the Journal, attention: Dr. Lampton.—Ed.

Rembrandt’s Good Samaritan, Then and Now

Of all his self-portraits, perhaps

we most love Beggar Seated on a Bank,

hunched in rags, scruffy hair,

broad nose, the mad glint in the eye.

Some say he is groaning in misery,

a palm extended out to us, who knows

whether for alms or recognition.

Though the artist thought himself ugly—

and preferred it to the beautiful,

his love of nature gave us beauty

despite his dead birds

or dogs doing what dogs do

as in the Good Samaritan.

There we see all—

a man who stops to help a stranger,

a ransacked traveler, beaten

by robbers and left for dead.

Others, so the story goes, including

a priest, saw but turned a blind eye

hurrying off to the other side of the street—

so that we catch our breath in shame.

But the Samaritan rushes to

douse his open wounds

then sets him on his own animal

and leads them to an inn.

When the Samaritan pays the innkeeper

and promises to return,

the artist melds the earthly (the dog

in the foreground) and the spiritual.

Some say the artist saw the parables

as an account of moments in his own life,

this master who harnessed the forces of

light and dark, who plunged

so deeply into the mysterious

that Van Gogh thought him

a magician. This man who suffered

the loss of three children and his Saskia,

who wiped his dirty brushes on his clothes

not caring a whit what others might think

was happy in the company of

workers and street people.

All his life a spendthrift,

finally, he died poor and

was buried in an unmarked grave—

Still we have the gift of his heart-work,

like deep music that moves

through rivers

opening and opening —

and the marvel of this etching

revealing the faces of all those outside

the inn, but not so the Samaritan.

His back is turned to us thus becoming

the embodiment of the injunction:

Do not let your left hand know

what your right hand is doing.

Though he remains anonymous,

his radiance burns white hot.

—Adele Ne Jame

Honolulu, Hawai’i