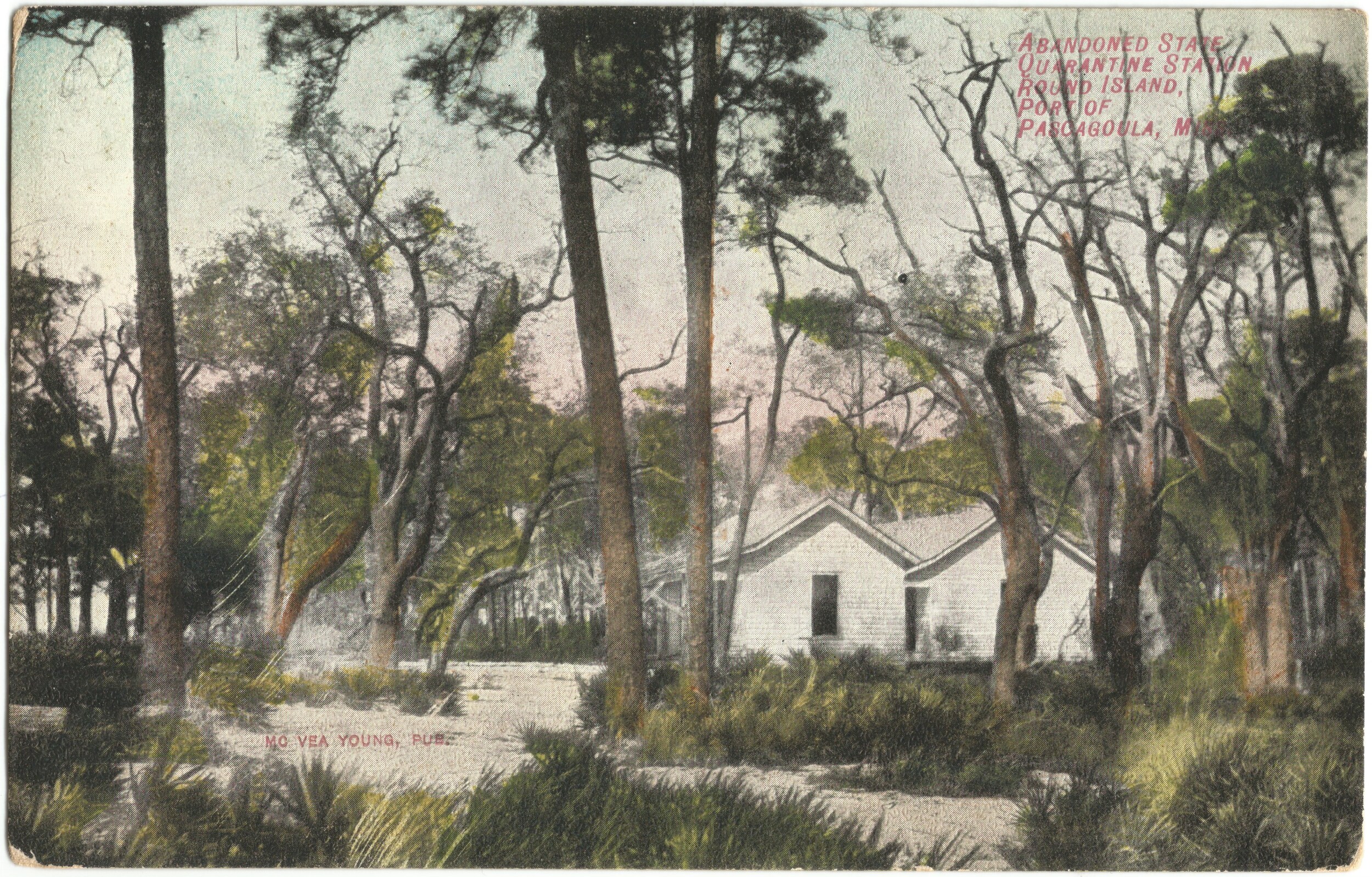

ABANDONED STATE QUARANTINE STATION, ROUND ISLAND, PORT OF PASCAGOULA, MISSISSIPPI— This image, which dates to 1908, is a postcard of the abandoned state quarantine station which was located at Round Island, a barrier island in the Mississippi Sound off the Port of Pascagoula. Published by McVea Young, it is postmarked from Scranton on October 28, 1908, three years after the final yellow fever epidemic of 1905. The station was operated by the state of Mississippi and local authorities from the 1850s until 1905, and then abandoned. Its first use as a quarantine station appears to have been during the yellow fever outbreak of 1858, and other Mississippi barrier islands, including Ship and Cat islands, also served in this manner to limit spread of disease, usually with a focus on yellow fever. In 1879, Ship Island was the site of the United States’ first National Quarantine Station, erected to protect port cities in both Louisiana and Mississippi. At quarantine stations, all incoming ships would be docked and inspected. Usually, ballast was dumped overboard, and a chemical combination of mercury and sulfur gas was sprayed on the decks to theoretically kill disease. Once cleared, a ship would receive a signed document stating that it was safe to enter the port. Ship Island even had a marine hospital to treat ill sailors. The Ship Island quarantine station would close in 1916.1

Yellow fever, also termed Yellow Jack, the Saffron Scourge, fievre jaune, Bronze John, and Black Vomit (the Spanish name is vómito negro), is the deadliest arthropod virus ever to emerge in the Americas. Both the molecular taxonomic research of viral strains and the annals of history reveal an African origin. Most authorities assert it was introduced to the new world by Aedes aegypti infested slave ships voyaging from West Africa, with its first recognition in the Americas occurring in Yucatan, Mexico, in 1648. Research suggests, however, that the disease was present in the Americas as early as 1498. Over the next two and a half centuries, yellow fever erupted with regularity in American and European port cities, causing hundreds of thousands of deaths and earning the virus deserved recognition as one of the worst plagues the world had ever seen. Two of the most significant North American epidemics occurred in Philadelphia in 1793 and in the Mississippi Valley in 1878. American epidemics were the result of the introduction of the mosquito vector and infected humans along routes of trade, especially sea and river ports and rail lines, with particular virulence associated with the Gulf region where its primary vector A. aegypti resided. Early attempts at control focused on quarantine and sanitary measures; yellow fever vaccination began in the 1930s. The devastation associated with American epidemics was an important impetus in the nation’s early public health and sanitation movements for the creation of city, state, and national boards of health. Yellow fever in the Mississippi area typically spread from the Caribbean, usually Cuba, then to New Orleans, then up and down shipping ports on the Gulf and along the Mississippi and along railroad lines. Yellow fever season usually began in New Orleans in June and would persist until the first frost, usually in November, which would eliminate the virus’s vector.2

Round Island, discovered in 1699, is an uninhabited island located 4 miles south into the Mississippi Sound from Pascagoula in Jackson County. While most of the island is covered in slash pine forest with a marshy interior, live oaks, a sand beach, and palm growth can be seen in the image as well. The island is a coastal preserve and the winter home and nesting grounds of many migratory birds, including a number of endangered species, such as ospreys and Great Blue Herons. In 1884, the island was 230 acres, but recurring hurricanes and natural erosion have impacted its size, with only 25 acres left following Hurricane Katrina. Current environmental restoration efforts hope to enlarge the island’s size to 70 acres. Besides the quarantine station, the island possessed a lighthouse on its southern tip as early as 1833. The original wooden structure was replaced with a brick lighthouse in 1859, which stood until 1998 when toppled by a hurricane. The island is also remembered as being used as a staging area by Venezuelan adventurer Narciso Lopez for a filibustering expedition in 1849 to liberate Cuba. Three ships and as many as 600 men gathered there, but U. S. President Zachary Taylor took steps against Lopez by blockading the island, seizing his ships, and encouraging his volunteers to return home.

Most of Mississippi’s ports from the 1850s-1905 had quarantine stations. Local boards of health usually required captains of vessels and shippers to report to the quarantine station prior to being allowed to enter the local port. Quarantine, derived from the Italian word “quaranta,” meaning forty, is a centuries-old word meaning the period, originally forty days, that an arriving vessel suspected of carrying contagious disease was ordered to lie off port in strict isolation. It has been used to manage outbreaks of infectious disease since the 13th century. The term applies to any period of isolation, restriction, or segregation imposed on travel or passage to prevent the spread of communicable disease.3 Historically, quarantine played an important role in Mississippi medicine, especially in the treatment of yellow fever and smallpox in the nineteenth century. Among the first laws passed by the Territorial Legislature in March of 1799 was one entitled “A Law Concerning Aliens and Contagious Disease,” which was directed to limit the spread of smallpox and other infectious disease. Early state law gave communities the authority to declare quarantine, and by the end of the nineteenth century this power would be vested in the Board of Health. The brilliant antebellum Mississippi physician, John Wesley Monette (of the village of Washington), first advocated in 1837 the use of quarantine for the control of yellow fever, which would become the region’s major public health weapon against the spread of this malignant and often fatal disease. In 1876, the Legislature passed law which created a Board of Health for the Coast counties (Jackson, Hancock, and Harrison) and empowered the board to prescribe rules and regulations for the enforcement of “quarantine and other sanitary measures” which they deemed “necessary and expedient.” The other image is the frontispiece to the 1898 regulations of the Mississippi Board of Health, which mentions quarantine and sanitation.4

The warlike aspect of quarantine can be seen in a revealing letter written at the pinnacle of the worst yellow fever epidemic in Mississippi’s history. Kentucky railroad builder C. L. Hardeman was facing “shotgun” quarantine stations along railroad lines, placed there by local governments to prevent disease spread. In October 1878, writing from Red Lick station in Jefferson County, Hardeman stated, “The mails have been and are entirely cut off from me— no train coming nearer than 15 miles so that I know but little of what is going on in the world. I have been literally cut off and confined to camp in the pine woods with the fever within 6 or 8 miles on three sides of me. My health has been as good as usual through the summer and I have laid the track and built the bridges on about 10 miles of road since I have been surrounded. My work is over now, I am ready to join my folks in Louisville as soon as I can get through the Quarantine officers. The guards have been doubled to keep me from getting away for fear I shall scatter the fever. Whenever the fever gets in my camp I intend to arm the men and capture the guards and go out. I shall respect their laws only so long as I am in no danger.”5 Written in the crucible of the epidemic, Hardeman’s letter reveals not only the panic of individuals and communities during quarantine but also the difficulties of non-voluntary enforcement and public resistance. With our recent pandemic, public discourse on use of quarantine has again returned to our politics. Quarantine remains one of the most useful and successful public health measures to battle propagation of disease.

If you have an old or even somewhat recent photograph which would be of interest to Mississippi physicians, please send it to me at drluciuslampton@gmail.com or by snail mail to the Journal. — Lucius M. “Luke” Lampton, MD; JMSMA Editor