Delirium, Day Sixteen after Surgery, Walking with Whitman

The surgeon looks into the cave of your eyes—

after sitting, his head in his hands,

outside your hospital room, they tell you,

for twenty minutes— thinking who knows what.

He leans in close, says quietly, I’ve been praying

all night for you— the light pouring in

through the tall windows from the Palo Alto hills,

a stark winter light, and my mother has been

praying for you. His voice is mesmerizing,

this healer you have come to adore,

his Persian accent, melodious cadence—

such music, you think,

though your throat tightens, black birds balancing

on a wire in the wind,

while a heavy stone of fear lodges deep in your body,

the morphine haze notwithstanding.

Still, though, you revel in the streaming light,

the stark winter light—

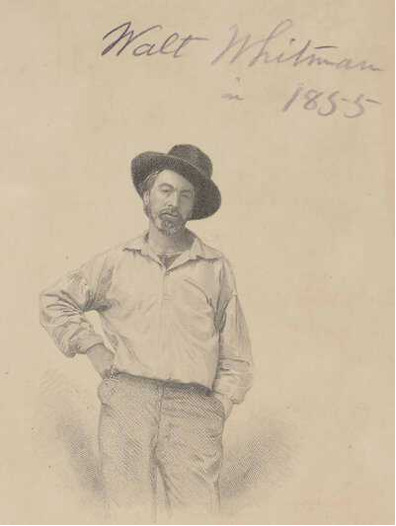

a Whitman light you would call it:

every atom of it belonging to you,

to all before and after you.

I don’t know what more to do for you,

your failing star of a surgeon says,

as if he might shake some life force

from the shoulders of his night vigil

into your room this fleeting January day.

Then all too soon a new routine begins:

every hour for fourteen hours

each day, his nurses force you from your bed,

a pillow girded around your middle,

IVs in tow, they command you

to circle the unit, this gleaming new epilepsy unit,

three times around it—every hour, they say,

no matter each step an intractable razor of pain.

Every room you pass, you see a child

propped up in bed, tall cone-head bandages

with tubes cascading down, their eyes glazed.

Then suddenly in a delirium of unaccountable

love, your friend Walt appears,

smart in his billowing white shirt—

He is walking with you—and the crowds he loved too,

those frantically rushing into their lives,

those multitudes from everywhere

on the ferry-boat who, like him,

saw the marvelous light pouring down

from the sky’s ocean, saw the East River’s

flood-tide, the ebb-tide. They congregate

around you so that you are no longer alone,

those beyond death, those before and after you—

across time, the stranger and the beloved.

Then all at once you hear the tide-song rising,

not unlike the song you were born hearing,

your mother’s lullaby—in Arabic she would sing

babbori rayeh, reyeh—babbori rayeh:

my boat is going, going, my boat is going—

or perhaps it’s the persistent nudge of a fugue,

not unlike Pachelbel’s in minor chords,

haunting but fresh,

that deep register repeating, rising—

O how it swells from their heart halls—

surrounding us all, consoling us all,

that mellifluous song

you always knew, one day, you would hear.

—Adele Ne Jame

Honolulu, Hawai’i