In 2009, I was recruited to organize and direct a burn unit to manage burn patients in Mississippi. At that time, there was no organized burn care in the state. The only burn unit in Mississippi, a private practice, had closed three years previously, and patients with burns were haphazardly managed with significant numbers of patients being sent out of the state for care.1

Approximately 150 patients a year were being sent to the Joseph M. Still burn unit in Augusta, Georgia. The director of that unit Dr. Fred Mullins,initially opened a clinic in Brandon, Mississippi, to help coordinate follow-up care for the Mississippi patients discharged from the Augusta unit. The number of patients grew substantially enough to lead Dr. Mullins to organize an extension of the Augusta practice in Mississippi, and I took the administrative and medical management roles for that extension.

At the time of my recruitment to burn care, I was in a hospital-based practice specializing in reconstructive plastic surgery with specific interest in hand surgery. That practice was rolled into the burn unit practice.

Dr. Mullins supported a statewide outreach to emergency rooms and trauma organizations to encourage referrals to the new burn center. A central call center was expanded to facilitate such referrals by giving providers promptly-answered phone access to transfer coordinators and accepting surgeons.

The Mississippi burn practice was organized as a “Burn and Reconstructive Center” to emphasize the availability of both acute burn care and secondary burn reconstruction within the capacities of plastic surgery practice.

The practice grew rapidly, exceeding the initial prediction of burn patients and case numbers. I continued to see patients for non-burn reconstructive problems, including hand trauma cases. The number of non-burn cases began to significantly contribute to the growth of the practice, and we included the promotion of such cases, including hand trauma, in outreach programs directed at referral sources throughout the state.2,3

The diversity of the practice and the contribution of non-burn cases led to the successful growth of the practice. Dr. Mullins used this mixed-practice model in multiple other extensions of the Augusta practice.4 In Mississippi, non-burn reconstruction achieved a volume equal to burn-related cases, and the practice became the highest volume center for hand trauma management in the state.3

This report will outline the growth of hand trauma within the Mississippi burn practice, describe illustrative cases, and discuss how the lessons learned from the hand trauma experience could be used to better organize statewide hand trauma management in the future.

Material and Methods

Monthly case conference lists were analyzed to identify the total number of surgical cases and subsets of acute burn cases, secondary burn cases, non-burn reconstruction cases, and hand cases.

A single year (2016-2017) was reviewed through billing records to identify all hand cases and to classify them as elective or emergency.5 This percentage of emergency care was considered typical and applied to the other 10 years to create estimates of emergency cases for each year.

No patient records were used in this review.

Results

For the purposes of this review, 2009-2010, the first year of this practice, was designated as year 1. Each subsequent year was numbered consecutively through 2019-2020, which was year 11.

Burn admissions increased dramatically after year 1 and leveled off between 580 and 630 patients a year during years 9 through 11 (Table 1).

Total cases increased throughout the period of study (Table 2).

Analysis of case categories (Table 3) showed that the greatest percentage of increase occurred for non-burn hand cases. This subset of non-burn reconstructive cases showed a 1156 % increase when year 11 was compared to year 1.

Analysis of year 8 (2010-2017) yielded a breakdown of elective and emergency cases for that year. Emergency cases totaled 377 (47%) of 805 hand cases and included injuries and infections treated at the time of the injury. They were referred from emergency rooms to the practice either as inpatient admissions, direct admission to surgery, or immediate clinic evaluation prior to surgery. These cases constitute the hand trauma population in this review.5

The 47% incidence of emergency trauma cases found in year 8 was extrapolated to the other year to calculate an estimate for hand trauma cases for an 11-year period (Table 5).

The increase in hand trauma cases was a substantial trend by year 4, and hand trauma cases exceeded 500 for each of the years 9-11.

Illustrative cases

Case 1

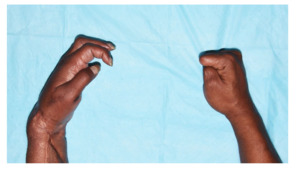

This 39-year-old man suffered a sharp amputation of his right thumb from a sheet metal edge. The amputation was just distal to the metacarpophalangeal joint. Replantation included bone fixation, tendon repairs, nerve and artery repairs, and dorsal vein repairs. Postoperatively, venous congestion was treated with leeches and anticoagulation for 4 days.6 The thumb survived (Figure 1). Subsequent healing included regaining of protective sensation and motion sufficient to pinch and grip. (Figure 2)

Case 2

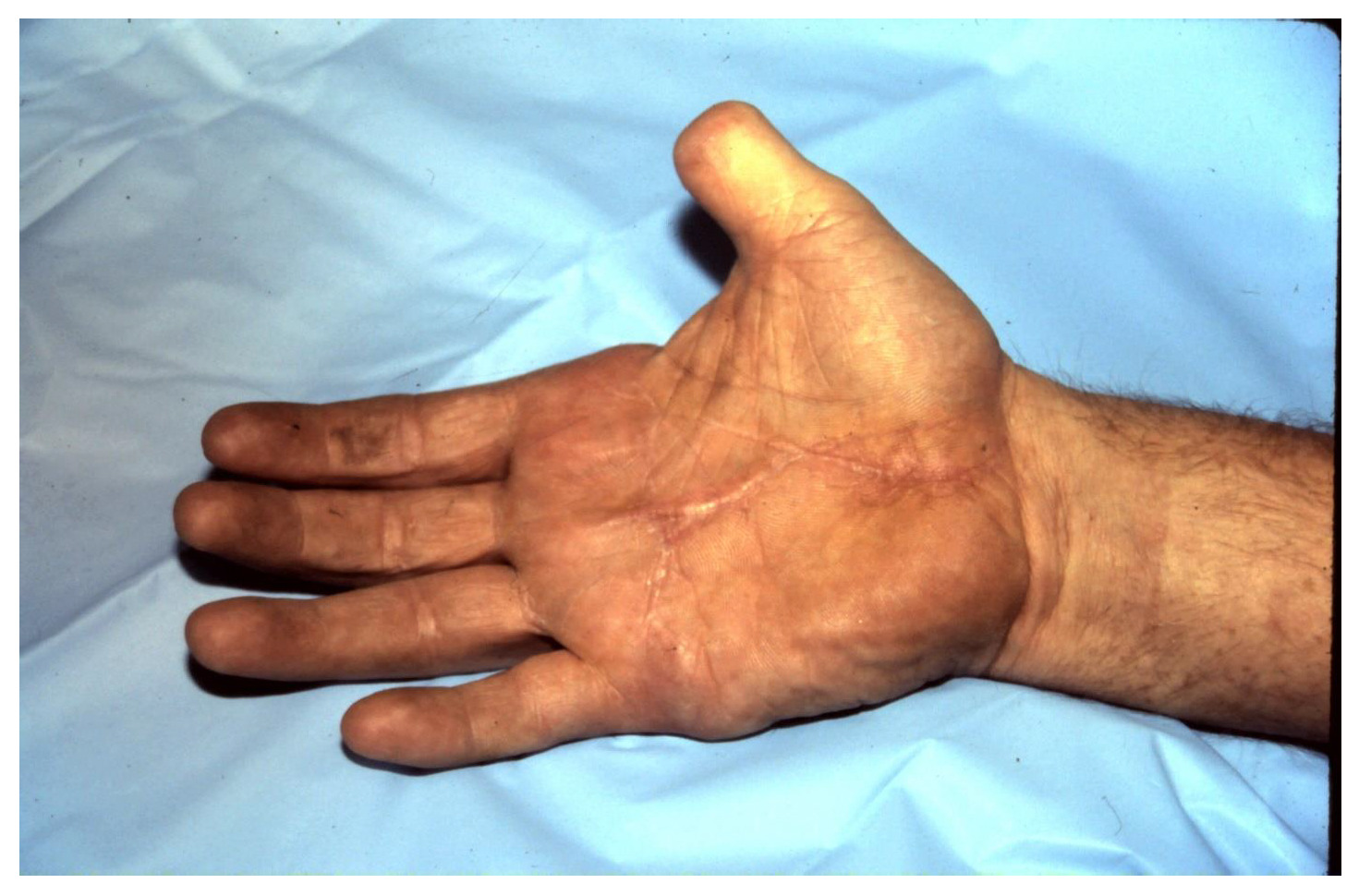

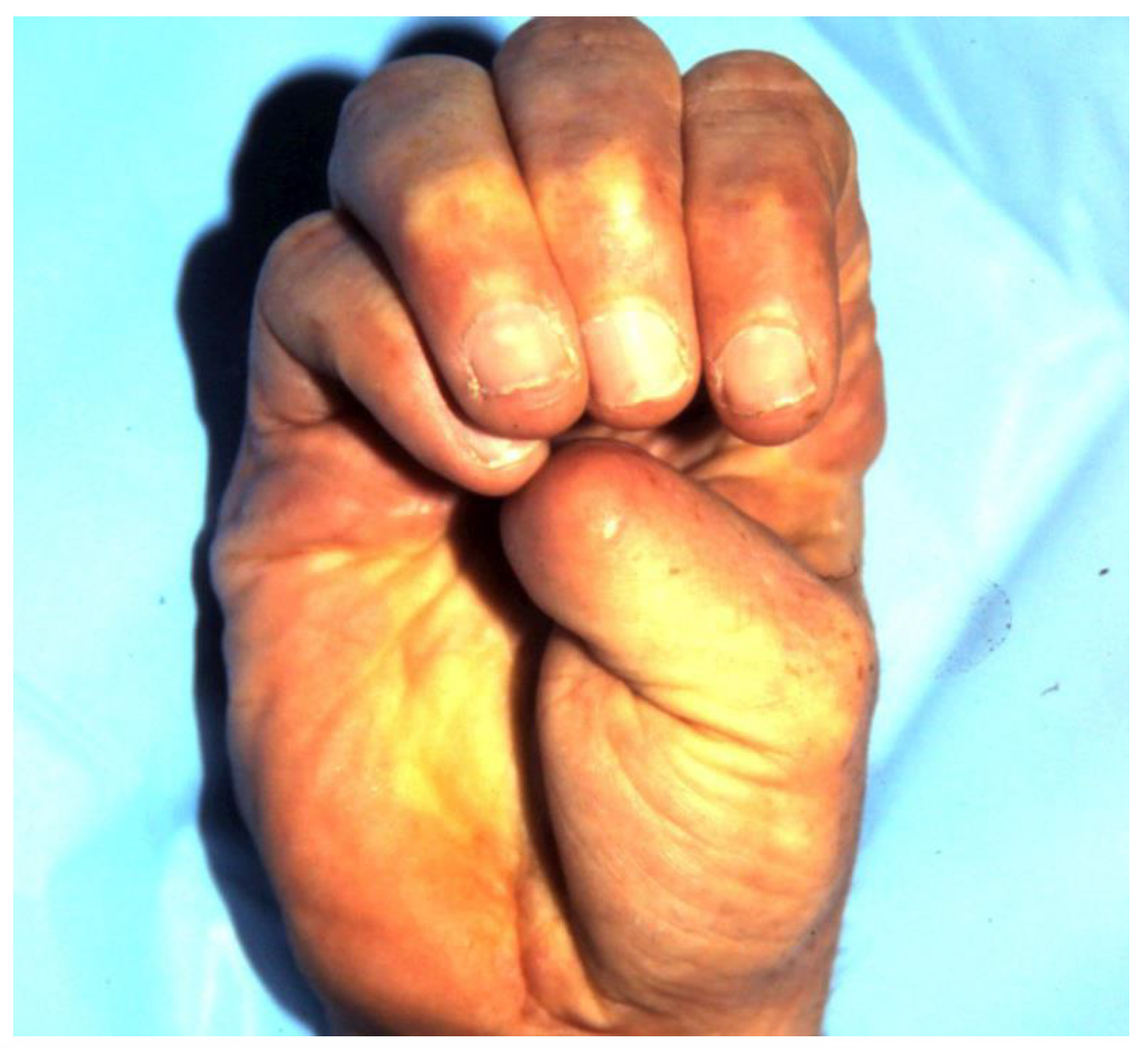

A 67-year-old man sustained injuries to all four fingers of his left hand (Figure 3). Surgery included replantation of the index with vein graft reconstruction of dorsal veins; replantation of the middle finger with skin preservation for venous drainage; flexor tendon and neurovascular bundle repairs of the ring; and distal phalangeal fracture fixation of the little (Figure 4). The patient regained sensation and sufficient motion for grip (Figure 5).

Case 3

A 36-year-old man accidentally amputated his right hand at the distal metacarpal level with a saw (Figure 6). Following replantation and secondary flexor tenolysis, he returned to work with functional grip and pinch. (Figure 7)

Case 4

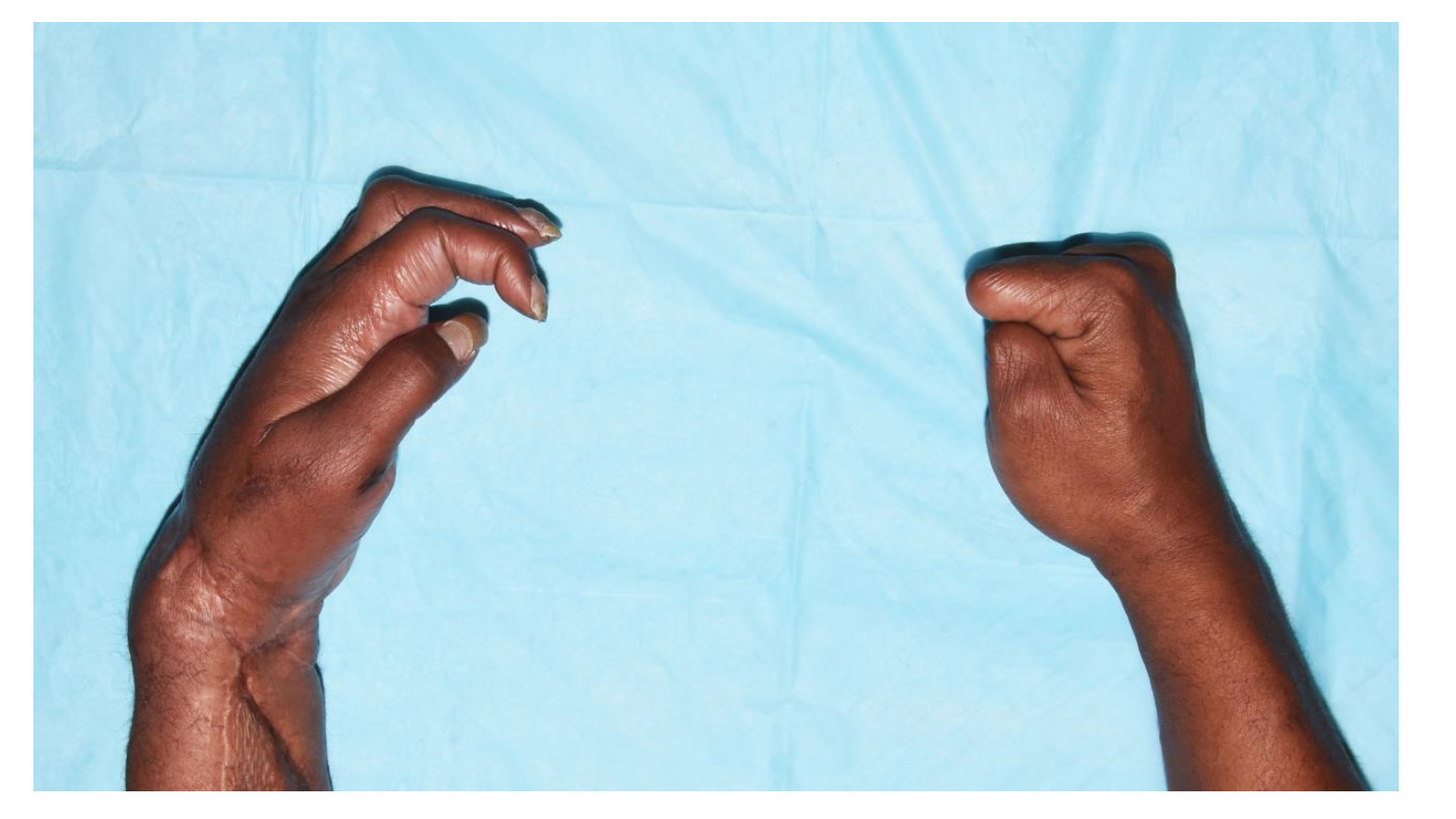

Both hands of this 33-year-old man were crushed in an industrial press. The left hand was disarticulated at the wrist, with avulsion of all extensor tendons and avulsion of radial and ulnar arteries; flexor tendons and median and ulnar nerves were in continuity (Figure 8). Surgical treatment included extensor debridement, forearm fasciotomies, wrist stabilization, vein graft repair of dorsal veins, and vein graft repairs of the radial and ulnar arteries (Figure 9). The patient later underwent two-stage extensor tendon reconstruction.

All fingers of the right hand were crushed and avulsed at proximal phalangeal levels (Figure 10). Local tissues were used to complete and close the amputation.

Six months later, the patient has sufficient function of both hands to sustain activities of daily living (Figure 10).

Discussion

Management of hand burns is a necessary part of any burn unit. Acute care, secondary reconstruction, and innovative procedures must all be available to maximize recovery of hand function, and all surgical options must be supported by specialized hand therapy.7–11

The organization of the Mississippi burn unit practice prioritized hand management skills and resources, and these assets, along with the referral center and outreach efforts, were readily adapted to the recruitment of emergency hand referrals for non-burn trauma.

The illustrative cases show how plastic surgery skills and concepts can deliver comprehensive care to hand injuries. These cases require management of skin injuries, tendon injuries, nerve injuries, and fractures. Devascularization and amputations require microvascular restoration of circulation, or optimal amputation closures if parts are not replantable.12 Secondary procedures, especially tenolysis, are commonly necessary to optimize results from initial salvage.13,14

Nationwide, access to comprehensive hand trauma care is known to be limited. Specific states report that less than 30% of their hospitals have full-time emergency specialist hand coverage.15,16 Within this limited landscape, availability of microsurgery is even more limited, with one Level I trauma center recently reporting that their team had attempted 101 replantations over 17 years, an average of 6 per year, with an overall failure rate of 71%.17,18

Similar data are not available for Mississippi, but a recent report by the state’s Level I trauma center is suggestive of the disconnect between the state’s trauma network and delivery of hand cases to the trauma center. The trauma center performed only 40% as many cases as this reports private practice (located 11 miles from the trauma center). Furthermore, the trauma center reported that 85-99% of its cases came from its own ER indicating that injuries outside the center were going elsewhere. Only one replantation was reported in these intervals.19

The impact on resident and fellow training at the trauma center includes loss of experience in microvascular replantation as well in the secondary procedures associated with successful replantations.13,14,20

With the state’s trauma center doing a limited number of cases based on presentations to its own emergency room, referrals for hand trauma began to come to the burn center’s practice in increasing numbers. By year 11, an estimated 543 hand trauma cases were managed in the private practice. Some of the factors that contributed to this magnitude of practice include:

-

a direct, accessible referral referring system connecting referring providers to transport and receiving services21;

-

surgical staff expertise capable of a complete range of hand surgery procedures, from microsurgery to amputations;

-

efficient operating room and anesthesia staff able to provide comprehensive emergency care and efficient operating room utilization;

-

specialized hand therapists who provided on-site care and coordinated remote care for patients referred from distant sites;

-

and an efficient, daily clinic capable of seeing large numbers of follow-up patients.

These elements could be assembled into a statewide referral system that could direct hand trauma patients to a designated center for comprehensive emergency care. As it is, hand trauma, like burn care, is managed largely outside of the state’s trauma center. Creation of a hand trauma center could build on the experience of this practice to simplify referrals and concentrate expertise. Managing the greater number of the state’s hand trauma patients in a center integrated with residency and fellowship programs would enhance training experience, potentially contributing to the development of more thoroughly trained surgeons and therapists who could raise the level of hand injury care throughout the state. The example of this practice illustrates the magnitude of hand trauma in Mississippi and provides a model for its efficient, comprehensive management. Institutional and administrative initiatives could build on this example to create a system and a center capable of providing uniform access to quality care for hand injury patients throughout the state.