INTRODUCTION

Increasing the number of individuals getting vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 in rural areas remains a challenge due to multiple factors including education, vaccine literacy and hesitancy, and access to vaccination sites.1 During the early Fall of 2021, the COVID-19 transmission risk level for most counties in Mississippi was considered very high, based on the reported number of COVID cases and the test positivity in the area.2 In September and October of 2021, investigators in the Risks Underlying Rural Areas Longitudinal (RURAL) Study core for the State of Mississippi used existing community partnerships with local advisory boards, community organizations, and state organizations to promote SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations in two rural counties in Mississippi (Panola and Oktibbeha Counties). These counties were sites of ongoing community engagement for the Mississippi State Core of the RURAL Study.

We describe the methods used to further engage and promote COVID-19 awareness in these communities, and address hesitancy and misinformation by leveraging trust and establishing community-based partnerships. We report the outcome of these efforts in carrying out COVID-19 pop-up clinics in these rural communities.

METHODS

The Mississippi Core of the RURAL Study is responsible for community engagement, forming community advisory boards, and promoting the RURAL Study among residents of Oktibbeha and Panola Counties. Local Mississippi RURAL investigators partnered with Community Advisory Board (CAB) members to identify geographic sites that need more vaccinations and assessed the willingness of the facilities to serve as a site for ‘pop-up’ vaccination clinics. CAB members concentrated on sites that could be accessible to rural residents within the county and ensured that rural residents would trust the personnel at the pop-up clinics. From 2018 to 2021, the Core engaged the communities by conducting focus groups centered on listening and understanding community concerns and interests from the health standpoint, meeting with county stakeholders to form Community Advisory Boards centered around health education, and promoting the RURAL study. In 2021, the Core also engaged the community by promoting public health at face-to-face community events including February Go Red Heart Health Events and Juneteenth events, meeting with community organizations and partners with a message of health, collaborating with nurses and physicians on promoting health initiatives in the community, and speaking at local churches and with church organizations on the RURAL study. Throughout 2021, The Mississippi Core team promoted health awareness and education by creating a Facebook page and hosting health education webinars concentrated on American Heart Association (AHA) focused themes throughout the year. RURAL investigators partnered with the Mississippi State Medical Association and the Mississippi Department of Health to assist in health education and promotion in these RURAL counties.

The Mississippi Core of RURAL Study team partnered with community organizations and state healthcare organizations to increase the number of residents vaccinated in these rural areas. The Mississippi State Medical Association and the Mississippi Department of Health helped to identify physicians and nurses to administer COVID-19 vaccinations in these rural areas. Working with local physicians on the CAB and local county hospitals that serve as the site for the RURAL study recruitment, investigators with local CAB members secured staffing, vaccines, and equipment and scheduled dates and times for popup vaccination clinics at four sites in Panola County and five sites in Oktibbeha County.

Pop-up clinics were promoted locally by physicians, church organizations, and community members and through RURAL investigators using both social media and news media. Facebook short talks were prepared, posted, and boosted across the counties promoting important educational information about COVID-19 vaccination before the pop-up clinic vaccination dates. The Mississippi Core Principal Investigator partnered with local physicians and pastors to promote virtual messages in the county through Facebook so that both information and familiarity may help with hesitancy among residents in the community. Investigators evaluated: 1) the success in setting up the vaccination popup clinics with staff and equipment at the intended sites on the day and at the time announced; 2) the number of persons vaccinated at each clinic; and 3) sex, age range, and race of those receiving vaccinations.

RESULTS

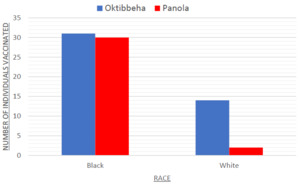

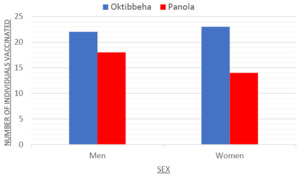

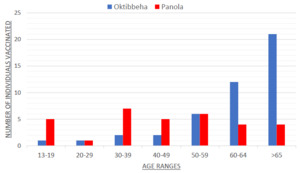

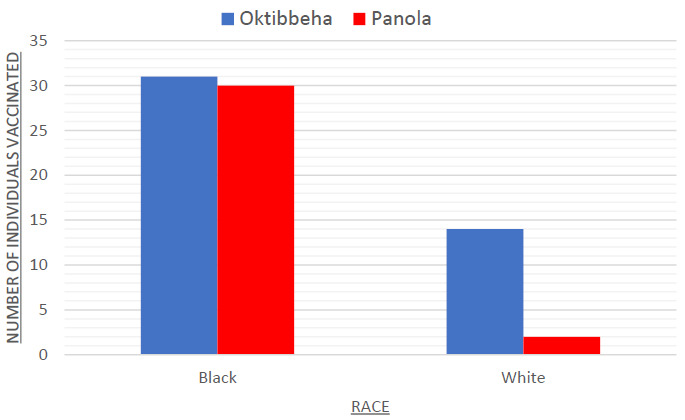

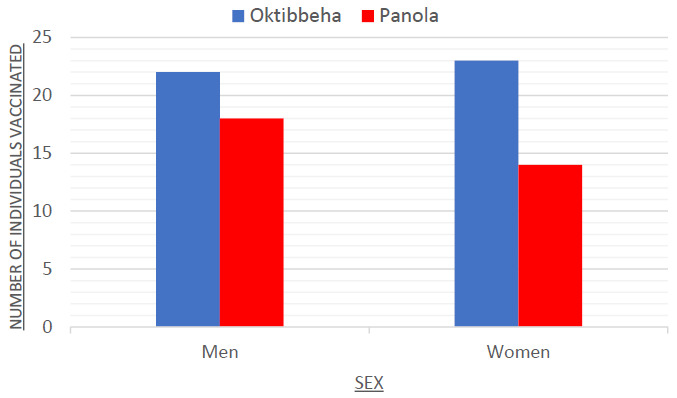

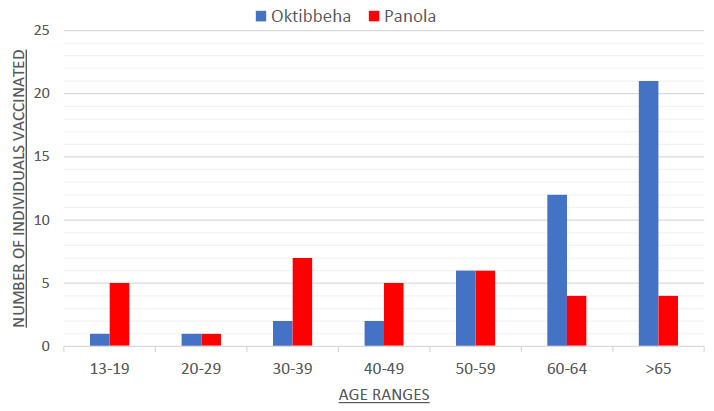

All nine COVID-19 popup vaccination clinics were successfully set up with appropriate staff and equipment available. A total of 77 individuals received vaccinations (32 in Panola County and 45 in Oktibbeha County). More men than women received vaccinations in Panola County, and all age ranges (12-19, 20-29, 30-39,40-49, 50-59, 60-69, ≥ 70 years) were represented. The majority of those receiving vaccinations in Panola County were Non-Hispanic Black residents. In Oktibbeha County, more men than women received vaccinations, and older age ranges (> 50 years) predominated. In Oktibbeha County, there was a more even balance of Non-Hispanic Black and White vaccine recipients. Panola County vaccination recipients were mostly first-time vaccinations whereas Oktibbeha County vaccinations were mostly booster doses. (Figures 1-3)

DISCUSSION

Existing cohort study infrastructure and human resources offered a unique opportunity to leverage community collaborations to promote vaccinations during a national pandemic. Promotion and encouragement are important for getting more rural communities immunized, however, vaccination rates are linked to public trust in the efficacy of the vaccine.3 One recent study finding supported two key components to gaining public trust 1) localizing information through education, and 2) modeling a system that pre-figures sincerity.4 The MS RURAL Core team built trust and a community-based infrastructure in the MS rural communities before organizing COVID-19 pop-up clinics in the two counties. At the suggestion of the community advisory board, COVID-19 awareness was incorporated into health education webinars throughout the year to more effectively reach rural communities.5 The use of webinars and other remote technology was a useful alternative to reaching rural communities in person due to the pandemic. State and public health organizations in the rural areas also participated in meetings hosted by the MS Core and in health promotion efforts in the counties.

An important aspect of the CAB that contributed to the success of the pop-up clinics was the diversity of the CABs. The board membership was balanced by age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Further, the CAB was comprised of individuals from different professional disciplines. Board members included physicians, nurses, pastors, civic leaders, community activists, community educators, and local county hospital representatives. Several members of the CAB were also members of community-based organizations which helped gain trust throughout the counties.6 By initiating a Community-Based Participatory infrastructure, the MS State Core was able to form partnerships with state and county organizations interested in reaching rural areas with known gaps in getting COVID-19 vaccinations. The concept of the vaccination pop-up clinics was supported by CAB members, and it was from their suggestions that we developed our strategy for implementation.

One unexpected result of initiating the COVID-19 pop-up clinic was the increased awareness among community members and the interest among community leaders and county stakeholders to initiate follow-up activities to get more residents vaccinated in their community. One effort was to increase vaccinations among those living in low-income housing complexes in Oktibbeha County. Also, a church not included in the list of churches in Oktibbeha County hosted its own vaccination pop-up clinic after church service with 50 congregation members getting immunized. The RURAL Study was promoted during this vaccination pop-up clinic while using the same group of local staffers to carry out the clinic.

CONCLUSION

In rural communities, it is often difficult to promote and distribute information about health and vaccine safety. By leaning on community leaders that are integral in these communities, we were able to expedite the process through leaders that citizens already trust. This process could serve as a valuable blueprint for future endeavors in which public trust is needed to distribute public health information and encourage citizens to engage in health protocols.

Implications

The findings from the current study suggest that cohort studies could leverage established trust and existing infrastructure in underserved communities to promote health initiatives that are marked by high rates of hesitancy such as COVID-19 vaccinations. By using health ministries, local physicians, and state health organizations we were able to address significant barriers that contribute to vaccine hesitancy in the community. Social media platforms (such as Facebook and Twitter), infographics, and face-to-face interactions were key mechanisms used to communicate health education, address misinformation, and address community questions that allowed for successful vaccination pop-up clinics in rural communities that had a history of vaccine hesitancy.

Abbreviations

CAB, community advisory board

RURAL, Risk Underlying Rural Areas Longitudinal Study