Prior to modern antiretroviral therapy (ART) and preventative strategies in the care for pregnancies complicated by HIV infection, an estimated 15,000 HIV-infected children were born to HIV-positive women in the United States through 1993.1 Despite an increasing prevalence of disease and approximately 5,000 women with HIV giving birth in the United States each year, in 2018, only 35 infants were born with perinatal HIV infection in the United States.2 This low rate of perinatal HIV transmission is due to the implementation of multiple preventative measures taken over the last 3 decades, which dramatically decreased the rate of perinatal transmission from 24.5% in 1993 to currently less than 1% in the U.S. and Europe.2,3 The key practice changes responsible for this success include universal prenatal HIV counseling and testing, antiretroviral therapy (ART) for all pregnant people with HIV, scheduled cesarean delivery for people with plasma HIV-RNA >1,000 copies/mL near delivery, appropriate infant antiretroviral (ARV) management, and avoidance of breastfeeding.

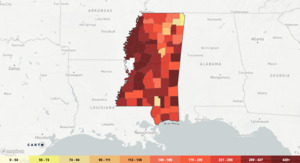

In Mississippi (MS), the prevalence of HIV infection is 402 per 100,000 persons (Figure 1).4 According to the CDC, there were 9,713 people living with HIV in MS in 2020. Four hundredand two people were newly diagnosed with HIV, ranking MS 6th in the nation for new HIV diagnoses among adults.5 Geographically, the prevalence of HIV in MS is slightly lower than the southern region but higher than the average rate in the United States which is 382 per 100,000 persons. Women account for nearly 20% of new HIV diagnoses in the United States, most via heterosexual transmission.5 This statistic remains true for MS with 18% of new diagnoses being female with a significant racial disparity: over 75% of new diagnoses occurred in black patients in the year 2020.5 The overwhelming majority (over 66%) of these diagnoses were made in those aged 13-34, which correlates to the age of the majority of patients with child-bearing potential.5 Perinatal HIV transmission occurs either in utero, intrapartum, or through breastfeeding, with most cases (up to 50%) of vertical transmission occurring intrapartum.6 Therefore, the objective of this review is to highlight optimal preventative treatments and practices to prevent maternal-to-child HIV transmission.

Preconception Counseling

Risk factors for acquiring HIV include condomless sex with a partner with HIV whose HIV-RNA level is detectable or unknown, recent sexually transmitted infection (STI), or injection drug use.2 Health care providers should discuss pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with those whose behaviors or experiences can be associated with HIV, including intimate partner violence, repeated post-exposure prophylaxis courses, or reporting feeling at-risk for HIV acquisition.2 PrEP is a proven prevention strategy as studies have demonstrated women with verified adherence to PrEP through detectible drug levels were protected against 90% of incident transmissions.7

The currently recommended regimen for receptive vaginal exposure to HIV is daily oral combination tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC), a drug that can be continued through pregnancy for those patients who become pregnant while taking the drug.8 Patients who are taking PrEP should be counseled to continue additional protection for the first 20 days after initiation of PrEP and should continue PrEP for 28 days after their last potential HIV exposure.8 Providers should offer routine PrEP follow-up, including testing for HIV every 3 months and counseling on signs and symptoms of acute retroviral syndrome.8 Preplocator.org may be used to locate local PrEP providers to all sex, race, gender, and sexual identity, including those that provide PrEP for uninsured patients.* At the time of this publication, six clinics were identified in the Jackson-Metro area able to provide PrEP at low or no cost to uninsured patients.

Optimal viral suppression, defined as plasma viral loads below the limits of detection at least 3 months apart, is key to ensure both maternal health in pregnancy and the prevention of perinatal HIV transmission.8 In HIV serodiscordant couples, there is effectively no risk of sexual HIV transmission to the person without HIV if the person with HIV is on ART and has achieved sustained viral suppression.8 Options to further reduce the risk of sexual transmission include condomless sex only at the time of ovulation or referral to a Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility specialist for intrauterine insemination (IUI) with washed semen.8 Specifically, for women with HIV+ partners, susceptibility to HIV acquisition is greater during periconception, antepartum, and early postpartum periods through 6 months than in the nonpregnant state.8 The use of PrEP in partners without HIV also effectively reduces the risk of sexual acquisition of HIV, which may be safely continued through the pregnancy.

For women with HIV+ partners, susceptibility to HIV acquisition is greater during periconception, antepartum, and early postpartum periods through 6 months.

Universal prenatal HIV counseling and testing

The current NIH guidelines (December 2021) recommend that clinicians initiate HIV testing with an immunoassay that is capable of detecting HIV-1 antibodies, HIV-2 antibodies, and HIV-1 p24 antigen.8 This test is referred to as an antigen/antibody combination immunoassay. Individuals with a reactive antigen/antibody combination immunoassay should be tested further with an HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody differentiation assay (referred to as supplemental testing). Individuals with a reactive antigen/antibody combination immunoassay and a nonreactive differentiation test should be tested with an FDA–approved plasma HIV-RNA assay to establish a diagnosis of acute HIV infection.8

Any pregnant patient presenting for treatment of a sexually transmitted infection or with signs and symptoms of acute HIV infection (fever, lymphadenopathy, skin rash, myalgia, headaches, oral ulcers, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, elevated transaminase levels) should be tested for HIV infection.8 Any patients with ongoing exposure to HIV should also be routinely tested every 3 months for HIV.8 These high-risk patients should receive a referral for initiation of PrEP if HIV testing is negative. Anyone without third trimester testing that is at increased risk should be tested on arrival to L&D, and the NIH guidelines state that all delivery units should have capability to result an HIV antigen/antibody combination immunoassay within 1 hour. Expedited maternal HIV antibody testing during the immediate postpartum period (or neonatal HIV antibody testing) should be obtained for all pregnant people without HIV testing prior to delivery.8

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) for all pregnant people with HIV

Adherence to ART in pregnancy is perhaps the single most important factor in preventing perinatal transmission of HIV. The Promoting Maternal and Infant Survival Everywhere (PROMISE) study was a large randomized clinical trial published in 2016 which demonstrated the superiority of ART over zidovudine-based prophylaxis for prevention of in-utero transmission.9 The study showed that ART successfully reduced the rate of perinatal transmission through 1 week of life from 1.8% (transmission rate in the zidovudine-based treatment arm) to 0.5% in the ART treatment arm.9 A recently published prospective multicenter French Perinatal Cohort followed >5400 women with HIV-1 who delivered from 2000 to 2014.10 In those women treated with ART at conception with undetectable viral loads near delivery, they observed zero cases of perinatal transmission, irrespective of the ART combination. In women whose ART was initiated in pregnancy with undetectable viral loads at delivery, perinatal transmission was low with a 0.57% mother-to-child transmission rate.10 The group with the highest observed rate of transmission (1.08%) were women treated at conception with a detectable viral load near delivery.10 Unfortunately, an HIV diagnosis may not be made until pregnancy with the initiation of prenatal care, making it impossible to achieve viral suppression at conception. Nevertheless, as this study demonstrates, undetectable viral loads at the time of delivery will confer a low rate of perinatal transmission, even in those patients not on ART at the time of conception.

The Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission recommends that patients with HIV who have achieved sustained viral suppression should continue their established ART regimen in pregnancy unless concerns exist about safety and inferior efficacy during pregnancy.8 Dolutegravir (DTG) was initially reported to have an increased risk of neural tube defects; however, new data shows that DTG does not contribute to neural tube defects more so than other ARTs in women who are HIV+.11,12 Like most other medications, the current safety data regarding antiretroviral drugs is derived from observational data as opposed to clinical trials. The time interval between initial registration of new drugs and the release of pharmacokinetics data and information regarding safety in pregnancy has previously been reported as 6 years.13

In providing HIV care during pregnancy, the patient’s disease status must first be assessed with plans to initiate, continue, or modify ART. The National Perinatal HIV Hotline is accessible to all providers for 24-hour, 7-days-a-week telephone consultation with an expert in perinatal HIV.14 Drug-resistance genotype evaluations or assays should be performed before starting a new ART regimen; however, initiation of ART should begin prior to drug-resistance testing results as earlier viral suppression has been associated with a lower risk of perinatal transmission.8

Most recent guidelines for initiation of ART in pregnancy recommend two nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors plus a third drug from another class.15 Initial pregnancy ART regimens are composed of TDF plus emtricitabine (or lamivudine) in combination with either the integrase inhibitor DTG or with the protease inhibitor darunavir/ritonavir.15 Pharmacokinetic and safety data are not available for the newest HIV drugs available such as doravirine, bictegravir and injectable long-acting cabotegravir/rilpivirine; therefore, they are not recommended to administer in pregnancy.16

The Ryan White HIV/AIDS program has provided funding for medical care, medications, and essential support services to low-income people living with HIV over the last 30 years, which has been a key component of the public health response to HIV in the United States.17 A Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program medical provider can be located on the website at findhivcare.hrsa.gov by entering a zip code to refer pregnant and nonpregnant patients without insurance for initiation and management of ART. In MS, HIV+ patients are treated at the University of MS Medical Center in the High-Risk Maternal-Fetal Medicine clinics, located at the Jackson Medical Mall in Jackson, MS, where they receive both infectious disease consultation and pregnancy/antepartum care.

Scheduled cesarean delivery for people with plasma HIV-RNA >1,000 copies/ml near delivery

The Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of zidovudine (ZDV) in reducing the risk of maternal-infant HIV transmission.18 Zidovudine given antepartum and intrapartum to the mother and to the newborn for 6 weeks reduced the risk of maternal-infant HIV transmission by 66% in pregnant women with HIV disease and no prior treatment with antiretroviral drugs during the pregnancy. This study corresponded to a decrease in mother-to-child transmission from 24.5% in 1993 to 7.6% in 1994.18 Intrapartum IV ZDV has clearly demonstrated its efficacy in reducing the rate of perinatal HIV transmission for women with high viral loads (HIV RNA >1,000 copies/mL), but the benefits for women with a lower viral load (HIV RNA ≤1,000 copies/mL) are less clear.19 MS perinatal HIV clinicians agree the benefits of intrapartum administration outweigh drug-exposure risks with recommendation to administer IV ZDV regardless of HIV viral load status. The recommended intrapartum ZDV regimen is from the original Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076: 2 mg per kilogram of body weight given intravenously over a one-hour period, then 1 mg per kilogram per hour until delivery.18 All hospitals in the state of MS providing labor and delivery services should have ZDV stocked and readily available should a patient with HIV present in active labor.

Patients should continue taking their antepartum ART on schedule during labor and before scheduled cesarean delivery.8 Previously published data derived from a 2001 meta-analysis of laboring pregnant women with HIV who were not on ART at the time of delivery revealed that with each additional hour of ruptured membranes, the risk of perinatal transmission increased by 2%.20 To reduce the rate of perinatal transmission in any HIV+ patient with a known detectable plasma HIV-RNA >1,000 copies/ml near delivery, a scheduled cesarean delivery prior to the onset of labor at 38 weeks gestation is recommended in order to offer the best protection against mother-to-child transmission of HIV.8 However, the protection provided by cesarean delivery is time-dependent, as previously described. The more challenging patient scenario for clinicians is delivery planning after the onset of labor or rupture of membranes. The NIH guidelines recommend individualized care for these patients, and consultation is encouraged using the National Perinatal HIV/AIDS Clinical Consultation Center.8,14

Other considerations for providing intrapartum care for patients with HIV include avoiding the use of a fetal scalp electrode and avoiding artificial rupture of membranes or operative deliveries, especially in those laboring patients with a detectable viral load.21 Delayed cord clamping may be safely performed as usual.21

Avoidance of breastfeeding

While ART does significantly reduce the risk of perinatal transmission of HIV in breastfeeding mothers, it does not eliminate this risk, and breastfeeding is not recommended for individuals with HIV in the United States.8 In HIV-positive patients who choose to breastfeed despite this counseling, risk-reducing strategies include consistent viral suppression with viral load assessments every 2 months and infant ARV prophylaxis to be continued 1-4 weeks after weaning.8 Prompt treatment of maternal mastitis and discarding any milk from the affected breast will also reduce the risk of transmission; accordingly, patients should be instructed to have a slow weaning process to reduce the risk of mastitis.8

Future Directions

The risk reducing strategies discussed in this manuscript have dramatically reduced perinatal transmission in the United States over the last three decades. The greatest prevention strategy of mother-to-child transmission is prevention of maternal HIV infection. Recently published data from a clinic-based PrEP program in Jackson, MS, revealed that only 22% of patients who were prescribed PrEP were continuously on PrEP, and half of those patients prescribed the medication stopped and did not restart.22 A PrEP-to-Need Ratio serves as a comparison for PrEP use vs. the need for PrEP by examining the number of PrEP users to the number of new HIV diagnoses; the state of MS currently has one of the lowest PrEP-to-Need Ratios in the nation.4,22,23 MS primary care providers can improve this number and further prevent HIV transmission in the state by initiating potentially uncomfortable conversations with patients at risk of acquiring HIV infection, especially those with child-bearing potential. MS primary care providers are encouraged to discuss PrEP with patients at risk of HIV and refer to our local PrEP providers, which may be located by accessing Preplocator.org.