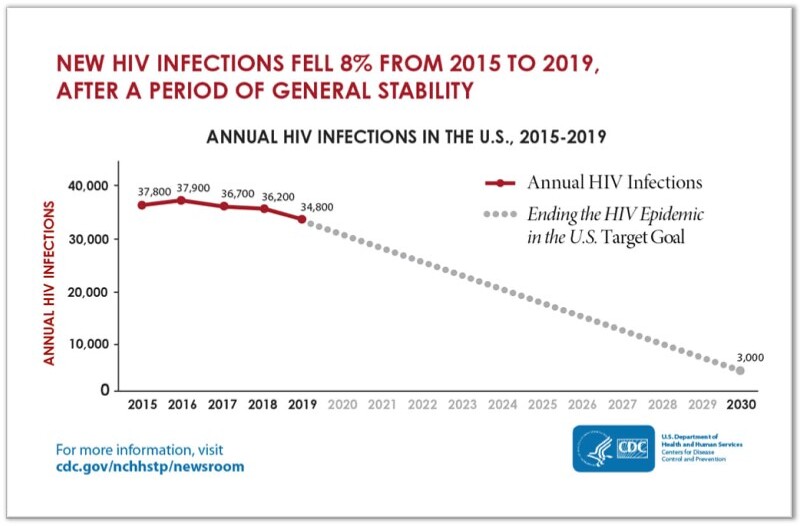

“The United States of America will be a place where HIV infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with HIV has high quality care and lives free from stigma and discrimination”. This is the vision of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) laid out in their HIV national Strategic Plan to end the HIV epidemic in the US by 2030. To realize this vision, the DHHS launched “Ending the HIV Epidemic: A plan for America”, an initiative recruiting multiple stakeholders and providing specific targets, one of which is to reduce new HIV transmissions in the US by 90% by 2030 (see diagram 1).1,2

Although decreasing rates of new infections between 2015 and 2019 reflect progress, an aggressive approach to meet the target is needed and multiple interventions must be harnessed.3 These include non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic tools, and PrEP is an essential one of the latter.

PrEP refers to the use of antiretroviral medications before HIV exposure to prevent acquisition in HIV-negative individuals at risk.4 It has its evidence base in iPrEx, a landmark trial in 2010, in which about 2500 men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women were randomized to either the antiretroviral drug Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate plus Emtricitabine (also known as TDF/FTC or Truvada) or placebo. The authors reported a 44% reduction in HIV incidence in the intervention group compared to the placebo group. While that result is reassuring, further analysis revealed that within the intervention group, patients with a detectable study-drug level experienced a relative reduction in HIV risk of 92% compared to those without a detectable level. This suggested that participants who were adherent to PrEP received substantial protection from HIV infection.5 This study paved the way for Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of TDF/FTC for HIV prevention in 2012, and other trials have since followed including Partners PrEP, ANRS IPERGAY, and the Bangkok Tenofovir Study, which validate PrEP in various at-risk groups.

But despite being available for more than 10 years and recommended by the US Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), PrEP is underutilized. Only 18% of the estimated 1.2 million people who are eligible for PrEP receive it. The demographics of this missed opportunity mirrors the uneven effects of the epidemic on persons of certain sexual orientations, gender identities, racial minorities, and geographic locations.1 For example, in 2018, more than half of new HIV infections occurred in the Southern United States and yet only 30% of PrEP users are in this region.1,5 A formal comparison of PrEP use to the HIV epidemic impact in a geographical area, using the “PrEP to need ratio”, revealed inequitable PrEP uptake in the South when compared to other regions.6 Multiple reasons have been suggested for this disparity including lack of access to PrEP providers, low rates of health insurance, low health literacy, multifaceted stigma, and low HIV risk perception.

Superimposed on these factors, a dilemma affecting healthcare providers exists, known as the “purview paradox”. Providers who are most familiar with PrEP, such as specialists in care of the people living with HIV, may not have a significant proportion of HIV-negative patients in their practice, while Primary Care Providers who regularly care for HIV-negative patientsx may not have the training to provide PrEP. Education of potential PrEP providers has been cited as a way of addressing this barrier.7

A simple starting point for a provider, in any setting, is to ensure that his or her patient has been screened for HIV according to the USPSTF recommendations that everyone between the ages of 15 and 65 get tested. This screening can be done with an HIV antigen-antibody test to detect chronic infection. If an acute HIV infection is suspected based on symptoms and exposure within the preceding four weeks, or if the patient has taken PrEP in the recent past, then an HIV Ribonucleic Acid Viral Load (HIV RNA VL) should be checked as well.8 For a high-risk exposure occurring within the past 72 hours, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is more appropriate, followed by reassessment for PrEP upon completion of PEP.

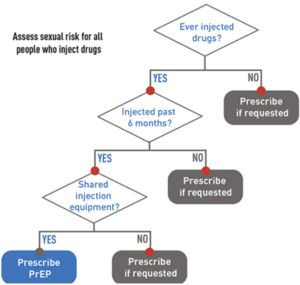

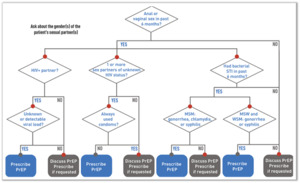

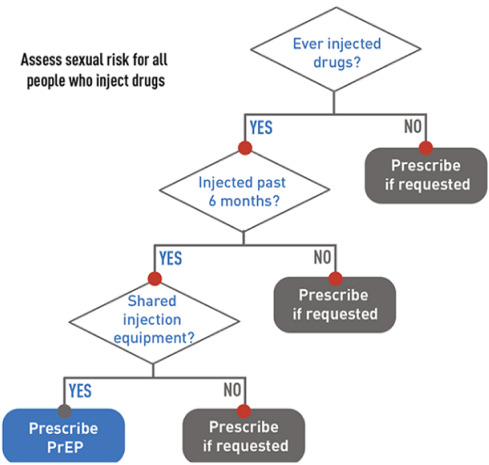

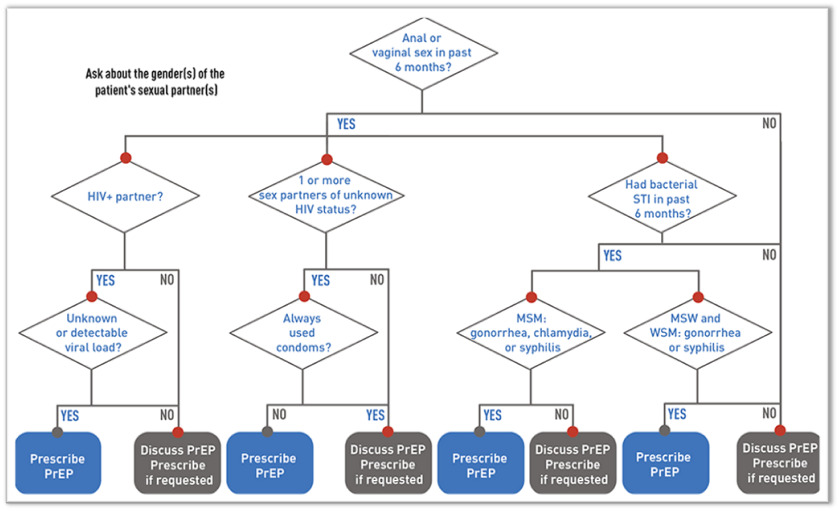

If HIV infection (acute or chronic) can be reliably excluded, the clinician should then determine, by probing further into the history, if the patient is PrEP-eligible (see diagram 2 and 3).8 Generally, it should be offered to all sexually active adults and adolescents at substantial risk of HIV acquisition and certain persons who inject drugs (PWID).

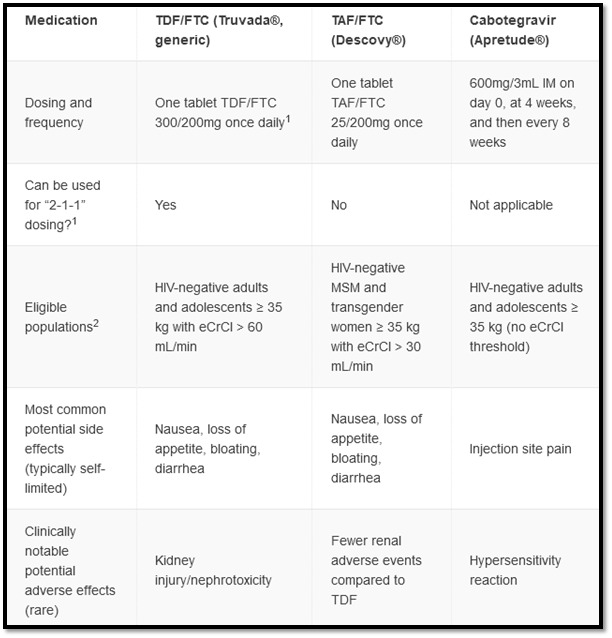

For patients in whom PrEP is indicated, additional laboratory testing is required. This includes testing for other Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs), renal function, lipid profile, and hepatitis B. Additionally, if an injectable form of PrEP is being considered, an HIV RNA VL should be part of the initial workup if not already done as part of screening. Candidates for PrEP have multiple available options which vary by route of administration and dosing schedule. Assuming they belong to a population in which that option has shown benefit, the optimal PrEP regimen is one that is most acceptable to that person and congruent with their sexual behavior, medication adherence, ability to anticipate sexual activity, and adverse effect profile (see diagram 4).9,10

Daily oral TDF/FTC is a recommended PrEP regimen for all populations at risk including PWID. This regimen is the most commonly prescribed for PrEP.8 Daily oral Tenofovir alafenamide plus Emtricitabine (also known as TAF/FTC or Descovy) is approved for men and transgender women and is preferred where creatinine clearance is between 30 and 60 mL/min or with an established diagnosis of osteopenia or osteoporosis. A non-daily TDF/FTC dosing option, a “2-1-1” regimen (also referred to as “event driven” or “on-demand”) exists for cis-gender MSM. Although not FDA-approved, this non-daily approach is supported by international clinical trials and is described in clinical guidelines.8,9 It synchronizes dosing with sexual intercourse events. Patients take two pills in the 2-24 hours preceding sex as an initial dose, then take one pill 24 hours after the initial dose and one pill 48 hours after the initial dose.

Cabotegravir (Apretude) is an FDA-approved, injectable PrEP option which may be appropriate for patients with significant renal disease, patients who have difficulty adhering to oral PrEP schedules, or those who prefer injections to oral dosing.8 Cabotegravir dosing includes an optional oral lead-in for the first month to assess tolerability. Whether the oral lead-in is chosen or not, the first two injections are one month apart and then are given every two months thereafter.

After the initial patient encounter and PrEP prescription, HIV testing should be repeated every three months for oral PrEP prescriptions or every two months for those on an injectable regimen. Subsequent visits involve screening for HIV, STIs, substance use disorders; assessing for adverse effects of medications; and re-assessing risk and the continued need for PrEP.4

The cost of PrEP therapy has been estimated to range between $360 to $16,800 per year for oral PrEP or $25,850 per year for injectable PrEP, not including the cost of labs and provider visits.11 Considering the USPSTF grade-A rating given to PrEP, most state-funded Medicaid plans and other health insurers cover PrEP therapy (at least one of the options) for little or no charge.12,13 For those with co-pays, options for covering additional costs include the Patient Advocate Foundation (https://copays.org/funds/hiv-aids-and-prevention) and co-pay assistance from the manufacturer (https://www.gileadadvancingaccess.com/copay-coupon-card). If the candidate is uninsured, obtaining medication can be facilitated by the manufacturer (https://www.gileadadvancingaccess.com/financial-support/uninsured), depending on his or her income, or via the Ready Set PrEP program, (https://readysetprep.hiv.gov) independent of income.14 For uninsured persons, clinic visits and labs can be provided with a sliding scale fee at certain health centers (https://findahealthcenter.hrsa.gov). Some states provide PrEP assistance that eliminates or reduces the costs of lab tests and clinic visits for uninsured patients, although Mississippi is not included in this list. This coverage gap may be an area that policymakers in Mississippi can explore, since cost can be a strong predictor of PrEP preferences, and efforts to scale up the use of PrEP are unlikely to succeed unless cost barriers can be sufficiently addressed.15

This article is intended to introduce and demystify PrEP and recruit a broad swath of clinicians to offer this service as many generalists and specialists encounter persons at risk. If you have identified a candidate and would like to refer him or her for PrEP, clinics at which PrEP is prescribed are available statewide (https://preplocator.org/). For providers considering incorporating this important mode of HIV prevention into their practice, a useful resource is the CDC PrEP Clinical Practice Guideline8 which outlines the frequency and specifics of follow up visits and testing once PrEP has been initiated.

According to an editorial co-authored by Dr. Anthony Fauci, the HIV epidemic in the USA could be ended quickly by expanding access to treatment to all persons with HIV, and PrEP to all those at high risk.16 This simple statement is a call to action to all providers to consider whether PrEP is indicated in each patient and participate in achieving this goal.