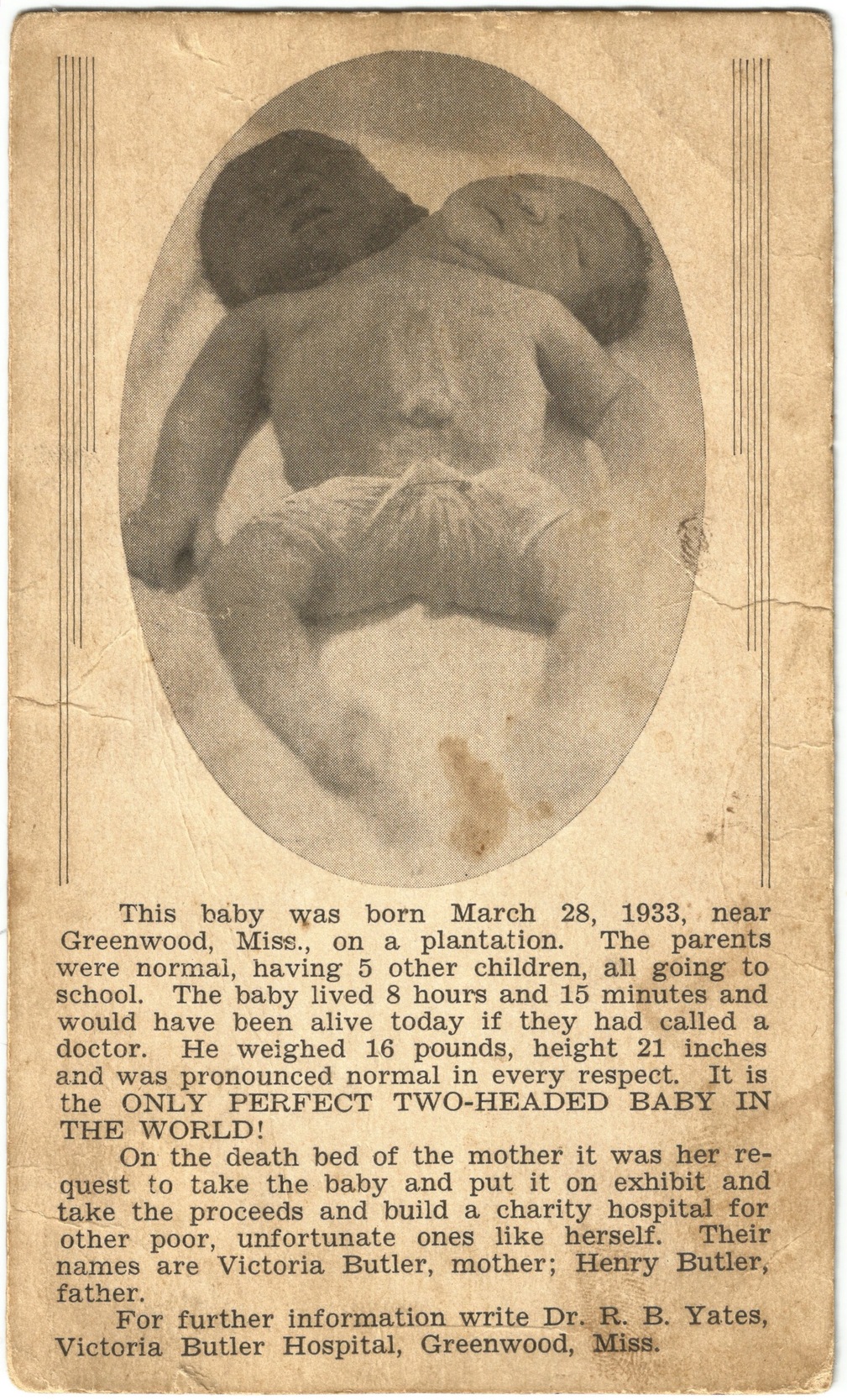

This image, which dates to early 1933, is a photograph of what was called “the only perfect two-headed baby in the world,” and it tells the remarkable story of an early African American hospital in Mississippi. The baby and the mother died soon after birth at home on a plantation outside of Greenwood, and their physician, Riley Barber Yates, MD (1888-1964), claimed that lack of medical care was the cause of their deaths. Clearly, there was a need for a charity hospital to serve Greenwood’s poor black population. The community rallied and built Victoria Butler Hospital, named for the baby’s mother. One of the hospital’s fund-raising efforts was the printing of a promotional card, pictured here. The card states, “This baby was born March 28, 1933, near Greenwood, Miss., on a plantation. The parents were normal, having 5 other children, all going to school. The baby lived 8 hours and 15 minutes and would have been alive today if they had called a doctor. He weighed 16 pounds, height 21 inches and was pronounced normal in every respect. It is the ONLY PERFECT TWO-HEADED BABY IN THE WORLD! On the death bed of the mother it was her request to take the baby and put it on exhibit and take the proceeds and build a charity hospital for other poor, unfortunate ones like herself. Their names are Victoria Butler, mother; Henry Butler, father. For further information write Dr. R. B. Yates, Victoria Butler Hospital, Greenwood, Miss.”[1]

Conjoined twinning is a rare medical phenomenon, occurring in only 1 in 50,000 to 100,000 births; because 60% of these are stillborn or die soon after birth, the true incidence is considered to be only 1 in 200,000 live births.[2] Accounting for only 0.5% of cases is the particularly rare form of conjoined twinning that occurred in Greenwood in 1933: dicephalic parapagus, partial twinning with one torso supporting two heads side by side.[3] There may be extra limbs and organs, and the degree to which they are duplicated varies from case to case and impacts survival chances. For example, two complete hearts may be present, and the extent of conjunction and abnormality of the hearts is the major predictor of survival. Most of the stillborns have cardiopulmonary or intestinal malformations; however, a small number have survived longer and even attained adulthood. Survival prospects appear to be enhanced if no attempt is made to separate the twins except in cases in which one twin is dying.[4] There are two main theories of how conjoined twins are formed. The more widely accepted is the “fission theory,” which asserts that conjoined twins result when a fertilized egg begins to split into identical twins, but its development is interrupted, and it becomes two partially formed humans melded together. Another theory is that conjoined twinning results from the fusion of monoamniotic twins who secondarily unite and blend.3

The Greenwood Commonwealth newspaper announced the creation of the memorial hospital in May of 1933, less than two months after the Butlers died: “The Victoria Butler Hospital named in honor of the poor, humble colored woman who recently gave birth to a well-developed baby, having two perfectly distinct heads on one body — a most wonderful and marvelous freak of nature beyond the understanding of scientific minds. The spirits of mother and baby are in paradise. They are asleep, but the body of the baby is kept here in preservation that people might see this freak of nature.” It continued the story: “Dr. R. B. Yates, who administered to this poor woman in her hours of untold distress of deliverance, was the major character in helping to bring about the construction of a hospital for the poor colored people of this city. Right on the heels of the above incident another poor colored woman who was shot and needed attention that only a hospital could give, was sent to Jackson, Mississippi for medical attention. They were crowded out and could not take her. She was then sent to Vicksburg, Mississippi, and the same was true there. She was brought back to Greenwood and died for the want of hospital attention.”[5]

The Commonwealth reported that in the aftermath of the Butlers’ death on a plantation and the death of the shooting victim who found no hospital care, White and Black leaders “were moved with compassion to change the situation. They set themselves to work to build a hospital for poor, unfortunate and helpless colored people.” Dr. Yates was the primary benefactor, who gave of his own personal means to erect the hospital “on the west side near the south end of Avenue J.” Others who assisted were Greenwood Mayor Clements, Dr. F. H. Smith, and B. B. Provine, Greenwood’s City Commissioner. Provine connected with the Depression-era Reconstruction Finance Corporation (R. F. C.), a federal loan and finance corporation created to help banks, municipal governments, and businesses, in order to “piece out Dr. Yates’ means for construction.” This federal government agency appears to have financed a loan for Dr. Yates to construct an impressive brick hospital, which faced Avenue I just off Broad Street and occupied the block of land back to Avenue J. Dr. Smith and Commissioner Provine also negotiated to have the R. F. C. provide much of the labor related to construction. The hospital had 32 beds divided between two wards, one for the men and one for the women, and included an operating room, laundry, and kitchen.

The furnishings and equipment for this large charity hospital came from several sources. Greenwood surgeon Dr. John Preston Kennedy furnished many of the beds and other equipment. (Dr. Kennedy died later that year, and his bizarre death became the focus of unproven murder charges against the brilliant and likely innocent Dr. Sara Ruth Dean, one of Mississippi’s first female physicians and Ole Miss medical school’s first female graduate.) Five of the beds were provided by Greenwood’s King’s Daughters Hospital. The county health officer, Dr. L. A. Barnett, secured a $600 dry sterilizer. Mrs. Nellie F. Cotter, the executive secretary of the Leflore County Chapter of the American Red Cross, provided all of the comforts, sheets, pillow cases, blankets, quilts, operating gowns and towels for the operating room. She, with Dr. Barnett, were also able to get T. B. huts for the new hospital from the T. B. Society.5 The Victoria Butler Hospital was a major undertaking, substantial in quality and size, and an ambitious vision of hospital care for the local Black population. The entire community of Greenwood, both White and Black, rallied enthusiastically behind Dr. Yates’ noble efforts to create a worthy memorial for Victoria Butler and her twins.

The local Committee of Colored Relief Association, which consisted of seven prominent African American leaders, ministers, and educators in Greenwood, described the hospital endeavor as “Herculean” and printed the following letter of praise in the local newspaper: "The hospital is a living monument to the heroes who put this project over. It is a beautiful hospital, now in its infancy. It is an ‘apple of gold in a picture of silver.’ We colored people are proud of it and of our kind-hearted white friends who have striven so earnestly to carry forward this movement. Therefore we, the colored people of Greenwood, are in hearty cooperation with Dr. Yates and his co-workers and will do all we can to help them carry this project to perfection. We also recommend that everyone of us share our scanty means in aiding this wonderful project. We also predict that someday this hospital will rank second, if not first, among the great hospitals and sanitariums of the country, such as Cook County Hospital, Chicago, Ill., and Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, Md.5

In the midst of the Depression, the hospital depended financially on philanthropy and public donations. Dr. Yates’ and the late Ms. Butler’s dream of using the preserved twins as a fundraising tool for the hospital appears to have been in many ways successful. In December 1933, Greenwood’s Dixie Theatre hosted a benefit for the hospital which featured “the World’s Foremost Lightning Escape Artist, In Person on Stage.” The advertisement noted, “WHITES AND COLORED WELCOME!” Besides the daredevil performance, the theatre featured the “World’s Only 2 Headed Human Baby Boy on Exhibit.”[6] This benefit reveals how the preserved body of the twins was exhibited in a circus sideshow manner in order to raise operating funds for the charity hospital. This freak show exploitation of a medical rarity seems to be well-intentioned and consistent with the entertainment values of that age. Other more traditional and civic-oriented fundraising efforts would be utilized over time to support the appreciated work of the hospital. In May of 1939 the Victoria Butler Hospital Circle of Greenwood, Mississippi, was created to seek funding for the hospital. The circle included three nurses as incorporators: Addie Idel Beaver, Lucille N. Dickerson, and Mable Ruth Buchanan. Over a decade, the hospital achieved its mission to become a critical medical facility in Greenwood caring for African Americans. In January 1940, the Commonwealth reported that after a car accident, a “negro” had been “rushed to the Victoria Butler Hospital in a Williams Funeral Home ambulance” to be treated for major injuries while a White passenger in the same automobile was “brought to Greenwood Leflore Hospital.”[7] A medical system thus evolved in Greenwood at that time which was segregated by race but was nevertheless still largely functional in medical emergencies, even down to the ambulance service.

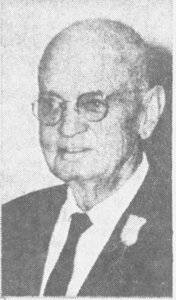

Dr. Riley Barber Yates, MD (1888-1964) was born in Philadelphia, Mississippi. He received his undergraduate degree from Valparaiso University in Indiana and graduated from the University of Tennessee Medical School in Memphis in 1912. He then did additional graduate work at Columbia University in New York City.[8] After several years of practice at Sidon, a small community located south of Greenwood, he began his practice of medicine in Greenwood in 1919. He served as a Captain in the Medical Corps of the 81st Division A. E. F. in World War I, serving in France for nine months “with distinction” and was even wounded in action.[9],8 During World War II, he served as a member of the local Selective Service board. Besides his work founding and operating the Butler Institute (as the Victoria Butler Hospital came to be called), he was much involved in the civic life of his community, including serving as a member of the Greenwood Park Commission.8 He married Lucille McKay Yates, and the couple had a daughter Majorie.[10]

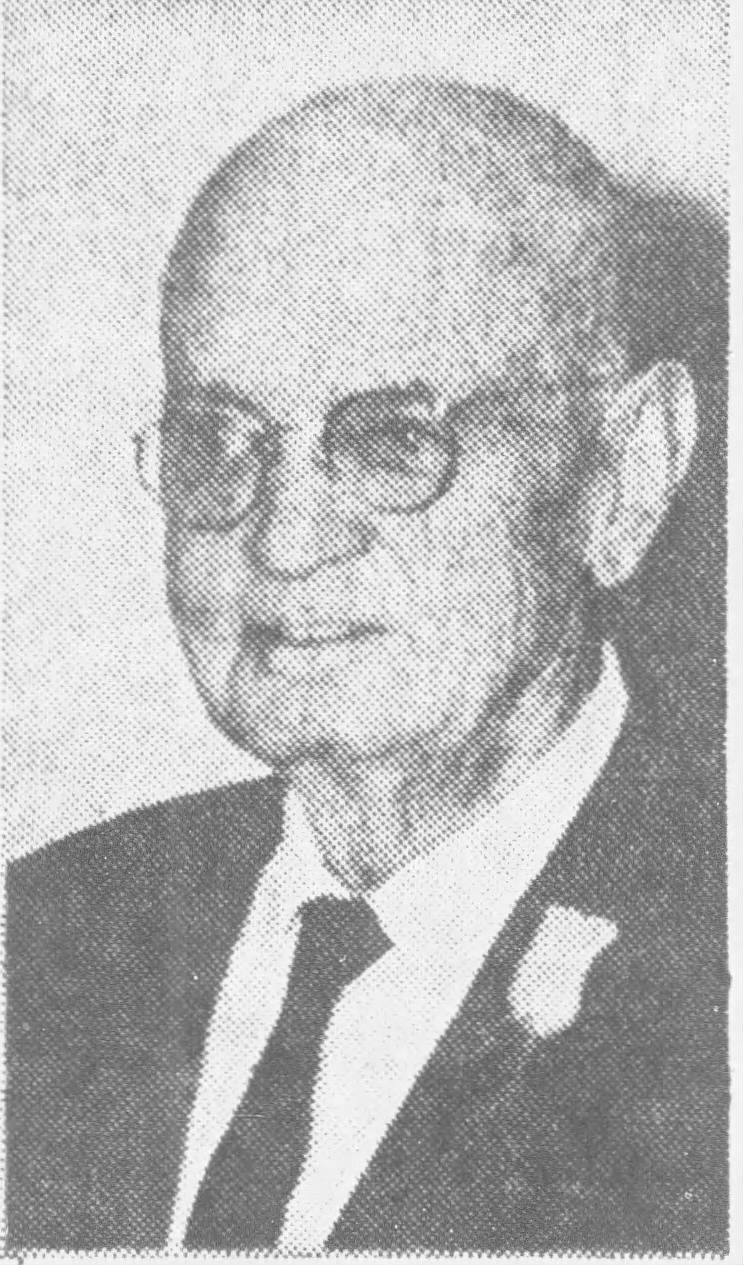

The Commonwealth announced in April 1942, “The Victoria Butler Institute, better known as Dr. R. B. Yates’ Colored Hospital, which was founded in 1933, celebrated the ninth anniversary yesterday. The hospital has enjoyed a steady growth and Idel Beaver, who made the first bed following the opening of the institution, is still on the staff as head nurse. Mable Buchanan, a nurse who has been on the staff for the past eight years, received her training under Idel Beaver, as did her three sisters, Melissa, Gladys and Susan Buchanan, who complete the nurses’ staff. The hospital is capable of bedding 32 patients.”[11] During its period of operation, the Victoria Butler Hospital was the largest and best equipped hospital serving the African American population in Greenwood, but it was not the only or first hospital focused on that mission. In 1910, Fred Monroe Sandifer, Sr., MD (1878-1946), a Tylertown native who had graduated from Tulane School of Medicine in 1901 and located in Greenwood in 1906, had established on Walthall Street the 12-bed Greenwood Colored Hospital (referred to by many as the Sandifer Colored Hospital).[12] Sandifer was a beloved and admired physician and surgeon in Greenwood, and like Yates, he was a leader in the civic development of the city.[13] The arrival of Dr. Sandifer’s son Fred M. Sandifer, Jr., MD (1909-1985), in Greenwood to join his father’s practice in January of 1937 after completing a residency and fellowship in surgery at Charity Hospital in New Orleans was a boost not only for Dr. Sandifer’s practice but also for his important work caring for the Black community in Greenwood. Sandifer’s hospital was a much smaller institution, but it played a significant role in the life of African Americans in Greenwood for decades. It was to Sandifer’s smaller hospital where prominent Black physician Dr. B. T. Williamson of Greenwood was taken for care after he poisoned himself in 1942.[14] It is unclear how the medical staff privileges at the institutions operated, but it appears that Yates and the Sandifers largely performed the medical and surgical management of the patients at their institutions.

As Dr. Yates’ health began to decline and he considered retirement, the owners of the two Black hospitals of Greenwood appear to have connected to discuss the future of their charity institutions. The arrival of young Dr. Fred and his surgical skills encouraged a larger facility for the Sandifers. In 1943, Yates sold his 32-bed hospital to Sandifer, who then closed his smaller hospital on Walthall Street and moved his hospital to the site of Victoria Butler Hospital on I and J Avenues. The local newspaper reported, “Dr. F. M. Sandifer has bought the colored hospital from Dr. R. B. Yates and has closed the hospital on Walthall Street, it was announced here today. The new hospital will be known as the Greenwood Colored Hospital, and is located on 708 Avenue J, corner Avenue I. Neva B. Jackson, R. N., is in charge of the new hospital, it was stated.”[15] Neva Bell Jackson, the Superintendent, was an African American nurse and at Dr. Sandifer’s death in 1946 wrote that he was “a friend not only of his race and of my race . . . [Dr. Sandifer] made heroic effort to save life, though humble and unfortunate that life may be . . . Words fail to express the deep appreciation we feel as a group because of his devotion to his profession, faithfulness to his work, and success of his achievements.”[16] After he sold Sandifer the hospital, Dr. Yates began a four-year step back from medicine, retiring completely in 1947. He died on October 28, 1964, in Greenwood, with his burial in Odd Fellows Cemetery in Greenwood, not far from the grave of Dr. Sandifer.8

Despite the noble work of the Victoria Butler Hospital and Sandifer’s hospital, there remained significant medical needs for African Americans in Greenwood and across the Delta region, especially for more complicated surgical cases. In 1937, civic leaders in Greenwood proposed the “erection of a hospital at Greenwood for the treatment of surgical cases for negroes” in the Delta region. The local newspaper encouraged the “active support of every citizen of this area” for the plan[17]although nothing appears to have materialized. The proposal seems less directed at Greenwood’s needs than the needs of the entire Delta and Greenwood’s central location for caring for African Americans in the region. The proposal also differed from Greenwood’s other Black hospitals in how the hospital was to be financed. Unlike the two Greenwood facilities, which were operated by philanthropic means (largely that of the physician-owners) and such creative fundraising efforts as exhibiting the body of the “two-headed baby,” the financing of the proposed hospital would be patterned after the successful model of Black fraternal hospitals, such as the Afro-American Hospital of Yazoo City, which was established in 1928 by the Afro-American Sons and Daughters and operated by charging a modest membership fee annually to Black members of their organization to utilize the hospital. This proposal sought to create a non-profit hospital corporation with an annual membership fee paid by the plantation owner. The effort was initiated by O. F. Bledsoe, a Leflore County planter, who proposed the erection of a 40-bed hospital at a cost of $100,000, with the cost of constructing and equipping the hospital financed on a voluntary basis by his fellow plantation owners, who would pay one dollar annually for each Black worker on his plantation. This was based on approximately 100,000 Black plantation workers. The site, as well as the utilities, would be provided by the city of Greenwood. “It is the plan to limit treatment to surgical cases, since plantation physicians are entirely competent to handle sickness of the most usual types but in most cases are without necessary hospital facilities,” asserted the Commonwealth. Bledsoe added, “The great need of our plantation negro population is prompt and efficient treatment for surgical cases, at a reasonable cost. Plantation physicians are entirely competent to handle sickness of the usual types. But even where they also practice surgery, there are not available locally the hospital facilities necessary for the proper handling of such cases . . . Competent surgeons would be retained by the hospital management, and service would be on a continuous twenty-four-hour, day and night, basis.”[18] The ambitious proposal was paternalistic in approach, but also a pragmatic vision of the modern concept of employer provided health insurance. Most of these plantations had long provided medical care via a plantation physician, usually without hospital services. The momentum for this hospital may have been absorbed by the Knights and Daughters of Tabor in their successful efforts from 1938-1942 to establish the Taborian Hospital in Mound Bayou, which was operated largely by membership fees but would be Black-owned and operated and dedicated to the same mission as the Greenwood proposal of 1937. Greenwood, along with McComb and Mound Bayou, was also among a few sites in the state considered for a location of a large general VA hospital for Black veterans of World War II.[19] Mound Bayou was chosen as the finalist for this $3,000,000 project.[20]

In February 1946, the commission overseeing the Greenwood Leflore Hospital, which was jointly owned by the City of Greenwood and Leflore County, made plans to expand and enlarge its facilities and decided to purchase for $6,500 the Greenwood Colored Hospital, both the property and all equipment therein.[21] The commission purchased the property but deeded it to the City of Greenwood and Leflore County. After this purchase in 1946, the Board of Governors of the Greenwood Leflore Hospital announced plans for the construction of additions and alterations to the Greenwood Leflore Hospital and the Greenwood Negro Hospital.[22] This purchase and invitation of bids reveal that Dr. Sandifer, before his death in April 1946, and his son “Dr. Fred” (as he was called by his patients) transferred their Greenwood Colored Hospital into the hands of the Board of Governors of the Greenwood Leflore Hospital, with a name change in this post-World War II period to the more modern descriptor of “negro” in place of “colored.” (Despite this change, the local newspaper continued to refer to the hospital as “Colored” as late as 1951.) This property transfer seems to have been the first effort to seek Hill-Burton funding for both hospitals. The elder Dr. Sandifer died soon after the sale, and after his death the Greenwood Negro (or Colored) Hospital appears to have operated under Dr. Fred’s and Neva Jackson’s management until the new Greenwood Leflore Hospital opened in 1952.[23] By 1949, the Board of Governor’s plan evolved from two separate hospitals, one White and one Black, to a single biracial $1,800,000 Hill-Burton hospital, the modern Greenwood Leflore Hospital, owned by the Leflore County Board of Supervisors and the City Council of Greenwood. The building was to be modern in every way with complete air-conditioning and built on a 16-acre plot in west Greenwood. The new hospital would contain 150 beds, “of which 110 will be for whites and 40 for colored.”[24] The new 140-bed Greenwood Leflore Hospital and School of Nursing, a Hill-Burton facility, would be opened on April 1, 1952, with both Black and White patients, although segregated, and Black and White students of nursing finally coming together at the hospital. This opening marked the end of the Greenwood Negro (Colored) Hospital, which was absorbed into the new facility. The end of the segregated status of patients would occur in 1969, as Medicare rules required accommodation on this issue and nurse training transitioned to academic settings.[25]

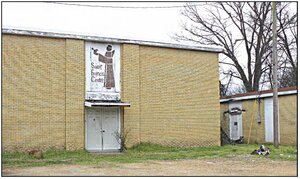

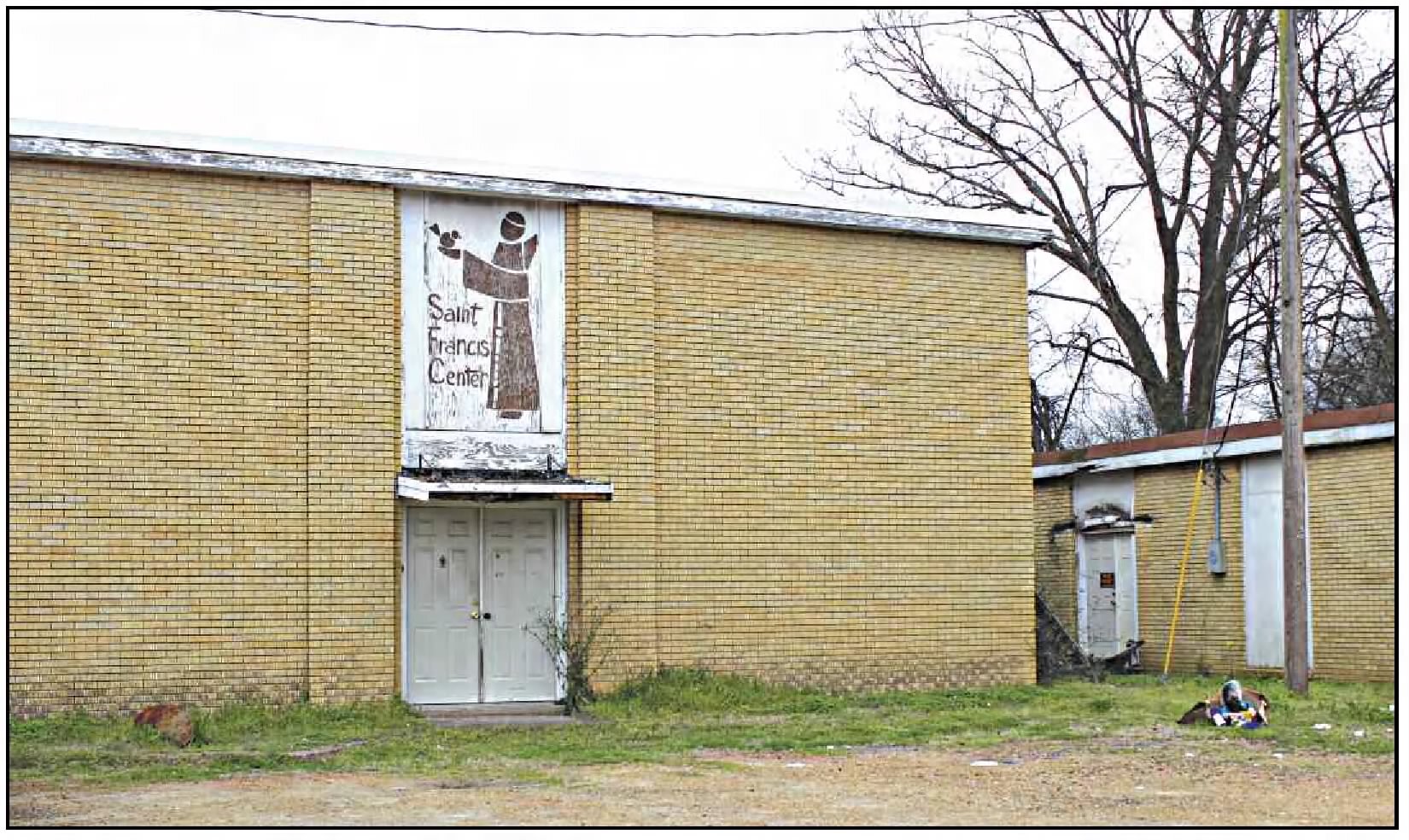

The old hospital’s well-constructed Depression-era structure off Broad Street between Avenue J and Avenue I would become in 1953 the St. Francis Center, a Catholic mission established in 1952 in Greenwood by Kate Foote Jordan and Father Nathaniel Machesky. The mission first started in a small store front on McLaurin Street, and part of its initial work was to visit the sick at Greenwood Colored Hospital. When the hospital closed after Greenwood Leflore opened its new hospital with its 40 Black hospital beds, the building was purchased by the St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church to serve as its St. Francis Center’s headquarters. As the Commonwealth reported, “More space provided room for more programs. Over the years, working with youth became an integral part of the center. Bible School, typing, and tutorial programs were offered along with boys’ and girls’ clubs, roller skating, a teen discotheque, an after-school program for troubled youth,” among other things. The center continued to offer a community health program which included a clinic, home nursing, and home deliveries by a nurse-midwife focused on the needs of the Black community.[26] As a safe haven for the African American community in Greenwood during the civil rights movement, the center was used for civil rights gatherings in the 1960s where protests and boycotts were planned, an African American newspaper was published, and it was once even fire-bombed during that period.[27] In 2019, Debra and Earnest Adams purchased the old hospital building and its grounds, and they continue its tradition of service as a community center offering educational programs for young people.[28] After two years of clean-up, the site opened as the Greenwood Community Center, offering a gym, conference room, and class rooms. The center provided many youth programs, including a virtual learning camp, financial literacy classes, and job placement services. Debra Adams, one of the new owners, commented upon its opening, “It’s like a breath of fresh air to know that we can open up this building and know that people can have a place to come.”[29] This sturdy structure, still standing and erected more than nine decades ago at the request of a dying young mother of dicephalic conjoined twins, continues to better the lives of the poor and unfortunate of Greenwood.

If you have an old or even somewhat recent photograph which would be of interest to Mississippi physicians, please send it to me at drluciuslampton@gmail.com or by snail mail to the Journal. — Lucius M. “Luke” Lampton, MD; JMSMA Editor

Victoria Butler Hospital promotional card, 1933. Lucius Lampton Collection, Magnolia, MS.

Bondeson, J. Dicephalus conjoined twins: a historical review with emphasis on viability*. J Pediatr Surg*. 2001; Sep;36 (9):1435-44. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.26393. PMID: 11528623.

Sahu, SK, Choudhury PR, Saikia M, Das TK, Talukdar KL, Bayan H. Parapagus dicephalus tribrachus tripus conjoined twin: a case report. Int J Sci Stud. 2015;2 (11): 211-213. doi: 10.17354/ijss/2015/86.

Basaran, S, Guzel,R, Keskin, E, Sarpel, T. Parapagus (dicephalus, tetrabrachius, dipus) conjoined twins and their rehabilitation. The Turkish J Pediatr. 2013;55:99-103. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://web.archive.org/web/20160131204838/http://www.turkishjournalpediatrics.org/pediatrics/pdf/pdf_TJP_1160.pdfhttp://www.turkishjournalpediatrics.org/pediatrics/pdf/pdf_TJP_1160.pdf. See also Kaveh, M, Kamrani K, Naseri M, Danaeian M, Asadi F, Davari-Tanha F. Dicephalic parapagus tribrachius conjoined twins in a triplet pregnancy: a case report, J Family Reprod Health. 2014;8(2):83-86. PMID: 24971140; PMCID: PMC4064765.

A Memorial to Victoria Butler. The Greenwood Commonwealth. May 15, 1933:8. Accessed Apr. 20, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/237634859/?terms=victoria butler hospital&match=1

Advertisement, Dixie Theatre. The Greenwood Commonwealth. Dec. 29, 1933:6. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/237677754/?terms=dixie theatre&match=1

Car leaves highway, two persons injured. The Greenwood Commonwealth. Jan. 22, 1940:1. Accessed Apr. 20, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/237707710/?terms=greenwood leflore hospital&match=1

Greenwood physician dies, funeral Friday. Clarion-Ledger. October 30, 1964:12. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/180550802/?terms=Greenwood Physician Dies&match=1

Doctor R. B. Yates moves to Greenwood. The Greenwood Commonwealth. June 25, 1919:4. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/255015471/?terms=Doctor R. B. Yates&match=1

Golden wedding anniversary is celebrated by Dr. and Mrs. Yates at lovely open house*. The Greenwood* Commonwealth. Sept. 6, 1961:3. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/256081106/?terms=Dr. and Mrs. Yates&match=1

Victoria Butler Hospital is now nine years old. The Greenwood Commonwealth. April 27, 1942:2. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/237795858/?terms=victoria hospital&match=1

Dr. F. M. Sandifer succumbs today. The Greenwood Commonwealth. April 15, 1946:1. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/237776875/?terms=Dr. F. M. Sandifer&match=2. See also McLemore, RA*. A History of Mississippi*, Vol. II. U P MS; 1973: 534.

Funeral services Dr. F. M. Sandifer. The Greenwood Commonwealth. April 16, 1946:1. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/237776903/?terms=Funeral Services Dr. F. M. Sandifer&match=1

B. T. Williamson Negro doctor dead by his own hand. The Greenwood Commonwealth. Oct. 6, 1942: 1. Accessed April 29, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/237776046/?article=cd0c4dbb-4df7-4c93-8c9f-0d07b014f38b

Dr. Sandifer buys hospital. The Greenwood Commonwealth. Sept. 1, 1943:1. Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/237796401/?terms=Dr. Sandifer&match=1

A Tribute to Dr. F. M. Sandifer, Sr. The Greenwood Commonwealth. April 24, 1946: 2. Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/237777111/?terms=Greenwood colored hospital&match=1

The negro hospital. The Greenwood Commonwealth. Aug. 21, 1937:4. Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/237711921/?terms=negro hospital&match=1

Plans are perfected here surgical hospital for negroes. The Greenwood Commonwealth. Aug. 3, 1937:1. Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/237710938/?terms=Hospital for Negroes&match=1; see also Beito, DT. Black fraternal hospitals in the Mississippi Delta, 1942-1967. J of Southern History. 1999;65(1): 109-140. The first Black-owned and operated hospital in the state was The Holmes County Colored Hospital, which opened Aug. 8, 1927, in Lexington, its Black "physician in charge, Dr. R. L. Redmond (1882-1952). Financing for the Lexington hospital came from local fundraisers such as barbeques, public donations from White businesses and supporters, but the majority came from dollars and cents donated from small Black community schools in Holmes County. Due to this fragile revenue stream, the Hospital would close in the Great Depression. See also Canvass for supplies for negro hospital. The Lexington Advertiser. July 14, 1927:10. Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/882281014/?terms=negro hospital&match=1; The colored hospital is formally opened. The Lexington Advertiser. Aug. 11, 1927:10. Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/882281111/?terms=colored hospital&match=1

Greenwood may be site for negro hospital. Enterprise-Journal. Aug. 27, 1945:6. Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/252079348/?terms=Greenwood may be site

3,000,000 V.A. hospital for negroes set for Mound Bayou. Enterprise Journal. Aug. 6, 1948:4. Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/252069361/?terms=%243%2C000%2C000 V.A. Hospital&match=1

An ordinance. The Greenwood Commonwealth. Feb. 11, 1946:2. Accessed April 29, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/237775225/?terms=Greenwood colored hospital&match=1

Invitation for bids hospitals, Greenwood, Mississippi. The Greenwood Commonwealth. Mar. 27, 1946:6. Accessed April 29, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/search/?query=invitation for bids&p_province=us-ms&ymd=1946-03-27

Greenwood nurse retires after 29 years of service. The Greenwood Commonwealth. May 1, 1984:3. Accessed April 29, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/255012691/?terms=Greenwood nurse retires&match=1; see also Services held for longtime physician. The Greenwood Commonwealth. May 9, 1985:1. Accessed April 29, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/249369563/?terms=services held &match=1

Greenwood Leflore hospital bids scheduled for January 24. The Greenwood Commonwealth. Dec. 8, 1949:1. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/256080686/?terms=greenwood leflore hospital bids&match=1

Greenwood Leflore Hospital and school of nursing. The Greenwood Commonwealth. March 18, 1954:4. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/253184408/?terms=greenwood leflore &match=2; see also Sturdivant, Jr., JW and Bacon, DR. African-American health care in early 20th century Greenwood, Mississippi: an overview. JMSMA. 2992:63 (1):10-14.

Pax Christi celebrating 50th anniversary. The Greenwood Commonwealth. July 5, 2002:6. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/search/?query=Pax Christi&p_province=us-ms&ymd=2002-07-05

Wilson, P. St. Francis Center: Open doors and helping hands. The Greenwood Commonwealth. March 22, 1990:55. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/237784012/?terms=St. francis center&match=1

St. Francis Center purchased. The Greenwood Commonwealth. Mar. 9, 2019:A1. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/541689726/?terms=st francis center&match=1

Edic, G. Community center will hold open house Friday. The Greenwood Commonwealth. Feb. 25, 2021:A1. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/743139024/?terms=Community center&match=1; see also Sorority gives $500 to Greenwood. The Greenwood Commonwealth. September 30, 2022:A1. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.newspapers.com/image/884329874/?terms=Sorority gives %24500 &match=1