Introduction

Body temperature is the result of an organism’s balance between heat generation and its gain or loss within the surrounding environment.1 The average human core temperature ranges between 36.1°-37.2° Celsius (C) (97°-99° Fahrenheit (F)).2 Hypothermia is defined as a decrease in body temperature to below 35° C (95° F). Hypothermia is subdivided into mild, moderate and severe depending on the patient’s core temperature and what symptoms are exhibited.3 Core temperature may be measured through the ear canal, bladder, rectum, mouth, or the esophagus.1 An esophageal thermometer in the lower third portion of the esophagus is the most accurate way of determining core temperature in an intubated patient.3,4 Initial temperatures obtained through the bladder and rectum are reliable as well but may be falsely elevated or delayed during rewarming.4 When the body is exposed to cold temperatures for an extended period of time, the peripheral vasculature constricts in an effort to reduce further heat loss. If the skin temperature decreases below -0.53° C (31° F), frostbite will occur from ice crystals in superficial tissues.5

Epidemiology

Hypothermia may occur in every climate on earth when an individual at risk encounters ambient temperatures below that of the core. Hypothermia is likely underreported as associated deaths are attributed to other pathologies. Recent data in the United States between 2018-2020 compares death rates associated with hypothermia by geographic areas. Data reveals death rates were highest among males residing in rural areas. Accurate environmental hypothermia data for Mississippi is not available but given the largely rural nature of the state, it is anticipated that a higher incidence of and death rate from hypothermia would be expected. The death rate for females was 0.11 per 100,000 in large metro areas and 0.40 per 100,000 in rural areas. The death rate for males was 0.29 per 100,000 in large metro areas and 0.93 per 100,000 in rural areas.6 Any age may be affected by hypothermia, but it is most prevalent between the ages of 30 and 50 years. Based on reported cases, mortality is estimated to be approximately 50% in people who are diagnosed with moderate to severe hypothermia even if they receive hospital care.3 Hypothermia risk factors include the extremes of age, hypoglycemia, alcohol use, general anesthetics, beta blocker use or burns. Hypothermia may also occur secondary to disorders such as stroke, dementia, Parkinson’s, anorexia nervosa, hypoadrenalism and hypopituitarism.3,4

Pathophysiology

Temperature regulation is controlled by the hypothalamus. Peripheral thermoreceptors, especially in the skin, signal the hypothalamus to make adjustments to maintain the core temperature. The body initially attempts to raise its temperature by shivering and conserves heat by peripheral vasoconstriction.3 The renal arteries also constrict resulting in greater volume being shunted to the central organs. The hypothalamus detects this increased volume and decreases its production of antidiuretic hormone causing a phenomenon known as cold diuresis. Initially, metabolism increases due to increased thyroid function along with elevated catecholamines from increased adrenal function.3,4 As hypothermia progresses, metabolic processes slow as will be discussed below.

Signs and Symptoms

Mild hypothermia is defined as a core temperature between 32°- 35° C (89°-95° F). The patient may experience general symptoms such as fatigue, nausea, confusion, and shivering. Although shivering is often the first hallmark of hypothermia, it may not always be present due to depleted energy stores as may be seen in hypoglycemia. On physical exam, the skin may be pale and dry, muscle tone will be increased, tachycardia and increased blood pressures may be noted.3

Moderate hypothermia is classified as a core temperature between 28°-32° C (82°-89° F). Patients present with lethargy or a decline in cognitive function. Paradoxical undressing may occur at this stage and shivering typically ceases. The risk for dysrhythmias increases with atrial fibrillation being the most common but clinicians should be aware that ventricular fibrillation may occur with movement of the patient.3,4

Severe hypothermia is defined as a core temperature below 28° C (82° F).3 Patients will be minimally responsive, if not unresponsive. Hypotension develops as heart rate and cardiac output are decreased. Pulses will be extremely difficult to palpate and should be checked frequently (every 30-60 seconds) as the risk of cardiac arrest substantially increases in this stage.3,4 Although little data is available in this situation, ultrasound should be a useful tool to assess cardiac function and the presence of peripheral pulses in this circumstance. The pupils will likely be fixed and dilated with minimal response to light. Further stiffening of the muscles and joints may mimic rigor mortis.7

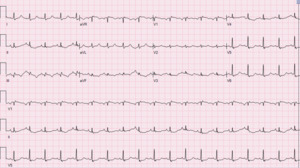

Electrocardiogram (ECG) findings typically found in significant hypothermia include:

-

Shivering Artifact

-

Bradycardia

-

Prolonged intervals (PR, QRS and QT)

-

Varying degrees of AV block

-

Osborn waves (also known as J waves)

-

Atrial fibrillation

-

Ventricular tachycardia

-

ventricular fibrillation

-

Asystole8

The Osborn wave is a positive deflection seen at the J point that is usually present in the precordial leads. The amplitude of the Osborn wave is proportional to the degree of hypothermia.3,8

Management and Treatment

If the patient is unstable on presentation, initial care should focus on the ABCs (airway, breathing and circulation). Every hypothermic patient should then be exposed with removal of all clothing, especially if wet.3 The process of rewarming begins with warm blankets and intravenous (IV) fluids that have been warmed to 38°- 42° C (100.4 – 107.6° F).4 Precautions should be taken to minimize movement of the patient due to the increased risk of dysrhythmias that could precipitate cardiac arrest. If a central venous line is required, the tip of the guidewire and catheter should be placed far from the myocardium to prevent dysrhythmias.3,4,7 In the mildly hypothermic patient, rewarming with external insulation such as warm blankets should be sufficient as shivering will increase heat production by 5-fold compared to baseline. Clinicians should be mindful of replenishing glucose stores if needed, especially in certain populations such as the elderly, diabetic and malnourished. Management of moderate to severely hypothermic patients requires more aggressive measures such as infusion of warm IV fluids, warm humidified oxygen, pleural lavage through bilateral chest tubes, peritoneal lavage, hemodialysis, arteriovenous rewarming, cardiopulmonary bypass or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).3,9 One of the more practical ways to rewarm intubated patients is with oxygen heated to a temperature of 42°- 46° C (107.6 – 114.8° F).9 Rewarming with methods such as warmed fluids, blankets and warmed humidified oxygen will raise body temperatures between 0.1°-3.4° C per hour.4 Whereas cardiopulmonary bypass, the most effective method, can rewarm up to 10° C per hour.3 Cardiopulmonary bypass and ECMO are reserved for patients in cardiac arrest or for the hemodynamically unstable. If available, unstable patients treated with ECMO have better outcomes.3,7 The use of many of these methods will vary depending on their availability, indications for procedures (e.g., a pneumothorax requiring tube thoracostomy) and physicians’ familiarity with them.

The American Heart Association’s (AHA) guidelines regarding basic life support in hypothermia recommends starting cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) if a pulse is not detected. If a shockable rhythm is present, defibrillation should be attempted but may not be effective until the patient is warmed to at least 30° C (86° F). Therefore, if the initial defibrillation attempt is unsuccessful, the AHA recommends ceasing further defibrillation attempts and focusing on compressions until the patient is rewarmed. Bradycardia is often seen in hypothermia, but cardiac pacing is rarely indicated. Medication toxicity should be considered due to reduced drug metabolism and systemic accumulation. The AHA recommends holding IV medications until core temperatures reach 30°C (86° F). A potential scenario is the severely hypothermic patient with hyperglycemia who has inactive insulin on board that upon rewarming resumes function. Administration of additional insulin while the core temperature is below 30° C (86° F) predisposes the patient to hypoglycemia upon rewarming. Once the patient has been rewarmed to this level, medications should be given with caution and increased duration between doses.9

The severely hypothermic patient may appear deceased. Many guidelines, adhering to the dictum “they are not dead until they are warm and dead”, recommend that the patient be rewarmed to a normal body temperature prior to declaring death.9 In many case reports of severe hypothermia, there has been full neurologic recovery in patients that have been resuscitated for prolonged periods of time supporting the theory that hypothermia is neuroprotective.1,4,7 Other sources argue that resuscitation may be guided with lab values such as potassium. When potassium reaches a value greater than 12 mEq/L and the patient persists in asystole, some clinicians argue that resuscitation is futile since hyperkalemia is an indication of irreversible tissue death.3,4 Inability to rewarm a patient should be considered a sign that death has occurred. Once the patient has been rewarmed, there is usually no indication for transfer to a specialized facility unless organ dysfunction has occurred that cannot be treated at the initial facility or hemodynamic instability is present requiring critical care services that are locally unavailable. If organ failure has occurred in a facility without appropriate specialty care, transfer will be necessary.

Frostbite

Frostbite is the most common complication resulting from hypothermia. This occurs when peripheral vessels constrict in an effort to conserve blood flow to the core organs. Frostbite occurs in peripheral tissues such as the fingertips, feet, nose, and ears.1 It typically occurs when the cutaneous temperature decreases below -0.53° C (31° F). At this temperature, ice crystals form within cells causing them to rupture. If frostbite is not treated, gangrene ensues and the tissue may not be salvageable.5 Early symptoms of frostbite include paresthesias and pain in the affected areas. The tissue will initially turn bright red in color followed by mottling and finally, the tissue will appear white. The area will also be insensitive to touch.1,5 First-degree frostbite, also known as frostnip, is the mildest form and is usually reversible since only the skin and subcutaneous tissues are affected. Second-degree frostbite is more extensive and blisters will form within 24 to 48 hours after the tissue is thawed. In this stage, the patient may have prolonged pain for weeks but the tissue will likely heal within a few months. Third- and fourth-degree frostbite, also known as deep frostbite, is much more extensive and involves the skin, subcutaneous tissues, tendons, and muscles. Blisters will be larger in size and insensitive to touch initially. Sensation will return within a few days of rewarming and pain will continue for months. The tissue will become gangrenous and will take at least 6 months to heal with permanent tissue damage.5

Treatment of Frostbite

In first- and second-degree frostbite, removal of wet or restrictive clothing and immersing the affected area in warm water should be sufficient in restoring circulation.1,5 If the fingers are affected, they may also be warmed by placing them under the patient’s armpit for at least 10 minutes. For more advanced frostbite, a warm water bath heated to 37°-39° C (98.6°-102.2° F) should be used to rewarm the affected area. The area should be submerged until color returns and the tissue softens. The use of warm water will be painful and therefore analgesics should be considered. Typically, first line treatment for pain will involve a combination of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs ibuprofen and aspirin. Once rewarming has been achieved, management consists of wound care, elevation if an extremity is involved and debridement of clear blisters. Ibuprofen should be continued due to its anti-prostaglandin and anti-inflammatory effects.10 Wound care should be focused on preventing infection. This may be done by soaking the area daily in a water bath combined with a germicidal agent. Gangrenous tissue should never be removed manually. The water bath should be heated to body temperatures and will also aid in removing any dead tissue. If the tissue is infected, antibiotics should be started. Current recommendations advise against early amputation unless the tissue is infected and unresponsive to antibiotics.5

Conclusion

Hypothermia is a medical emergency that may present in any population in any climate. Mortality in hypothermic patients is high and therefore, the pre-hospital course of management is extremely important. Dysrhythmias are common in hypothermia. Rescuers and hospital staff should be aware that slight irritation to the myocardium caused by movement may easily cause cardiac collapse. There are many ways to rewarm a patient and the decision is dependent on the capabilities of the clinician and facility. Lastly, frostbite is the most common complication of hypothermia. Tissue will be salvageable in mild and moderate frostbite while permanent damage is inevitable with severe cases. Management should be focused on wound care and pain control.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have nothing to disclose.