Introduction

The case discusses the diagnosis and management of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) observed in a patient with recent vancomycin exposure as well as explores the need for more structured treatment protocols for the disease. The patient in this case suffers from DRESS manifesting primarily with cutaneous involvement and associated acute kidney injury (AKI).

Case

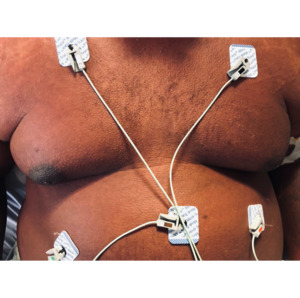

The patient is a 41-year-old African American man who initially presented to the emergency department with a worsening generalized maculopapular, intensely pruritic, erythematous, dry rash with a duration of one day prior to arrival. The rash involved the patient’s abdomen, chest, lower back and bilateral arms and groin. The rash was reported to have begun centrally on the chest and spread in a centripetal fashion. Images of the rash upon initial presentation are pictured below.

Additional complaints included nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, throbbing posterior headache, low urine output, diminished appetite, cephaledema and anasarca. The subject also had been experiencing chronic diarrhea without blood or mucus for the past month. Physical exam at time of initial presentation also revealed lymphadenopathy involving the patient’s chest. The patient had no prior episodes of similar events. Pertinent medical history involves osteochondroma of the right distal tibia and ankle two years prior with a recent case of post-surgical osteomyelitis following an ankle reconstructive surgery two months prior to the emergence of the aforementioned symptoms. A five-week course of Vancomycin and Rocephin were administered via PICC line for treatment of a complication of osteomyelitis following the patient’s most recent ankle surgery. Five out of six weeks of planned antibiotic treatment were administered when therapy was interrupted over concern for the emergence of the rash on the patient’s chest.

Upon initial presentation in the Emergency Department, vital signs were within normal limits. CBC and CMP were unremarkable with the exception of elevated monocytes (1.1 x 103 cells/mcL) and eosinophils (1.0 x 103 cells/mcL). Sodium and chloride were low at 133 mmol/L and 99 mmol/L, respectively. Renal function demonstrated an elevated creatinine of 1.50 mg/dL and decreased eGFR of 66 mL/min/1.73m2. Albumin was found to be low at 3.3 g/dL and ALT was mildly elevated at 64 units/L. AST was within normal limits. A chest x-ray was performed which showed clear lungs and no acute chest findings. Benadryl and fluids were administered in the Emergency Department, and the patient was discharged home with loratadine.

The patient returned to the emergency department two days later with a complaint of unresolved/worsening symptoms, chiefly involving worsening pruritis and generalized rash that had spread further distally. The patient stated that ibuprofen, acetaminophen, loratadine and diphenhydramine taken at home failed to relieve symptoms. Physical examination revealed the rash had increased in surface area to involve more of the patient’s abdomen, and now the lower back and bilateral groin. Clear fluid was observed in the external auditory meatus bilaterally. Tachycardia was noted with a heart rate of 125 bpm and regular rhythm. Additional vital measurements were unremarkable, and the patient was apyretic. Abdominal ultrasound was performed over complaints of mild abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea which showed no sonographic abnormalities of the pancreas, biliary duct, gallbladder, and spleen. The aorta and IVC were unremarkable. Confirmatory CT yielded no significant findings. Urinalysis was ordered to evaluate for proteinuria secondary to nephrotic syndrome or interstitial nephritis, which demonstrated only trace protein without other abnormalities. CMP now demonstrated leukocytosis with WBC count of 17,000 cells/mcL and platelets of 369 x 103/mcL. Further elevations in neutrophils (11.0 x 103 cells/mcL), monocytes (2.1 x 103 cells/mcL) and eosinophils (1.7 x 103 cells/mcL) were observed in comparison to the day prior. ESR was elevated at 19. An antinuclear antibody screen was performed once during this time and was found to be negative. Coagulation studies revealed elevated PT of 16.8 and INR of 1.38, which were suspected to be caused by the acute inflammatory process as was the leukocytosis. PTT was within normal range at 30.40. CMP demonstrated worsening renal function compared to measurements collected two days prior with elevated BUN of 11, creatinine of 1.89 up from 1.50, and albumin of 2.9 down from 3.3. ALT remained unchanged and elevated at 64. Lactic acid was noted to be elevated at 3.0 and alpha-1-glycoprotein was also elevated at 0.6 g/dL, suspected to be due to the acute inflammatory process. Total serum protein was low at 5.3 g/dL. The patient was subsequently admitted to the hospital under care of Internal Medicine.

Initially, DRESS, secondary amyloidosis, and a cutaneous manifestation of T-cell lymphoma (i.e., Sézary syndrome) were in the differential, with eosinophilia trending upward suggestive of DRESS. A punch biopsy of the patient’s right dorsal forearm over a prominent area of the rash was obtained and sent to pathology. The patient was started on hydroxyzine and prednisone for pruritic relief. Lactated ringers were continued. The patient adamantly rejected the administration of intravenous antibiotics over concern of allergic reaction. A repeat CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was significant for prominent bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy without axillary, hilar, or mediastinal involvement. The lungs were clear and there were no pericardial or pleural effusions identified. Transesophageal echocardiography was performed over concern of bacteremia, which showed normal systolic function and no evidence of vegetation. Eosinophilia continued to trend upward with a high of 6.3 x 103 cells/mcL. After two days of observation, WBCs trended down to 16.8 from a high of 25.6 the day prior. Eosinophils decreased to 2.7 x 103 cells/mcL. ALT continued to decline to 149 from a high of 217. Renal function improved with a BUN of 13 and creatinine of 1.31 (creatinine was expected to increase due to prednisone therapy). Hyponatremia improved and remained stable with a sodium level of 136 from a low of 129. The patient was subsequently discharged and instructed to remain on prednisone and to return in three days for laboratory assessment of liver and kidney function.

On follow-up appointment, physical exam yielded no significant findings. The rash had decreased in severity by this point in time but was still evident in the original pattern of distribution. Improvement of the rash was noted on bilateral extremities as well. Pruritis and cephaledema were also improved. Vitals signs were stable, and tachycardia was no longer present. Urinalysis and laboratory tests showed no significant findings and demonstrated an improvement in both renal and liver function. WBCs had decreased to 11,100 cells/mcL. Eosinophils remained stable at 1.1 x 103 cells/mcL. Renal function demonstrated a creatinine of 1.35 mg/dL. ALT and AST were elevated but improved at 104 and 49 units/L, respectively. Hyponatremia was evident but remained in acceptable range at 133 mmol/L. The subject was discharged with instructions to return to the hospital if symptoms returned.

Approximately three weeks later, the patient was found to be positive for Clostridium difficile during a GI consultation for an ongoing one-month history of continuous diarrhea, prior to the onset of symptomology discussed in this case. GI found potassium, BUN and creatinine to be highly elevated, and the patient was instructed to return to the Emergency Department for evaluation. The patient had no new complaints on arrival. Physical examination was unremarkable, and the patient’s rash was no longer evident. The patient was subsequently admitted again for evaluation of acute kidney injury (AKI). Hypertension was now present with a blood pressure of 167/103. CMP revealed a potassium level of 5.0. Urinary protein was found to be 30. IV fluids were administered. Renal ultrasonography revealed minimally increased bilateral renal cortical echogenicity without evidence of hydronephrosis, suspicious masses or other significant findings and was otherwise unremarkable. Hyperkalemia improved with a value of 5.1 down from a high of 6.4 after amiloride was removed and Lokelma 5g PO BID was added. The patient was placed on amlodipine 5mg, which significantly reduced blood pressure to 122/77 compared to the day of admission five days prior. C-ANCA was elevated at 2.3. Over the course of hospital admission, WBCs reached a high of 12.2 x 103 cells/mcL, BUN of 49, and creatinine peaked at 7.58. The diagnosis of AKI was made according to AKIN classification and RIFLE criteria. Eosinophils remained at 0.1 during the course of admission. WBCs continued to trend downward to 10.6 x 103 cells/mcL.

By the fifth day of admission, laboratory values showed a consistent improvement in kidney function in a linear fashion, with creatinine of 2.67 and BUN of 29. A CT-guided core renal biopsy was performed for further evaluation of renal involvement. Fidaxomicin 200mg BID PO was started for C. difficile. The patient was instructed to follow-up on an outpatient capacity for continued monitoring of AKI and was discharged the following day.

Pathology of the renal biopsy specimen demonstrated no significant reaction to IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, C1q, kappa, lambda, or fibrin on immunofluorescence. These findings were supported by electron microscopy. There was notable focal mild interstitial fibrosis in trichome-stained sections. There was diffuse interstitial inflammatory infiltration involving the majority of biopsy tissue. The inflammatory infiltration was associated with interstitial edema and tubular injury. The inflammatory cells are lymphocytic predominant but also contain a large number of plasma cells and scattered eosinophils. The tubular epithelial cells showed reactive changes with no intranuclear inclusions. Pathology made the diagnosis of acute tubulointerstitial nephritis.

Discussion

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) is a rare but potentially lethal adverse drug reaction that presents with an extensive cutaneous rash as well as eosinophilia, lymphadenopathy, variable visceral manifestations, and lymphocytosis. The incidence of DRESS syndrome is approximately 10% of cases end in death.1 Early recognition of DRESS, cessation of the culprit drug, and supportive care are critical in ensuring the best possible outcome for the patient. The time between administration of the offending drug and the emergence of symptoms can range from 2 to 8 weeks, and the duration of the disease is often drawn out by recurrent flare-ups following the initial resolution of symptoms. Numerous drugs have been associated with DRESS, but allopurinol, antibiotics, and aromatic anticonvulsants are responsible for the majority of cases. One review of electronic health records dating from 1980 to 2016 demonstrated that Vancomycin alone accounted for 39% of DRESS cases.2 Management, regardless of disease severity, includes maintaining adequate support of electrolytes, fluids, and nutrition with close monitoring of labs, imaging, and clinical status. Cases that are considered mild with little or no visceral organ involvement generally only require topical emollients or corticosteroids to manage the cutaneous symptoms in addition to the supportive care previously mentioned. More severe presentations, like the patient detailed in this case report, require treatment with high-dose oral or intravenous corticosteroids. Cyclosporine can also be utilized for patients with contraindication to corticosteroids or in those cases that are resistant to treatment with high dose corticosteroids.3

DRESS syndrome is associated with systemic symptoms that include fever of 101.3 F and higher, hematologic irregularities, lymphadenopathy, and a wide range of other abnormalities associated with cutaneous and visceral organ involvement. Eosinophilia and leukocytosis are the two most commonly encountered hematologic manifestations of DRESS, but patients can also develop neutrophilia, lymphocytosis, monocytosis, and atypical lymphocytes.4 Lymphadenopathy in DRESS occurs in the majority of cases and can be seen simultaneously in different regions of the body. Organ involvement with DRESS varies and can include any visceral organ in the body with the liver being the most common. As many as 90% of patients experience single organ involvement, whereas the involvement of 2 organs is less common and seen in 35% of patient presentations.4 Seen even more seldom in DRESS is the involvement of 3 or more organs like in our patient mentioned above. According to the literature, approximately 20% of DRESS cases present in this fashion.4

The cutaneous manifestations of DRESS are often the first abnormalities noticed and can be quite profound. Edema of the face and head is said to be the hallmark of the disease by some and was indeed significant in our patient. Usually, patients also experience a symmetric maculopapular rash that can progress into diffuse erythema. Images 1-6 of our patient demonstrate how the rash’s appearance can vary depending on time since onset and location on the body. Pruritus frequently, but not always, accompanies the rash. Although some cases can fail to present with the typical cutaneous symptoms, this is rarely seen with an estimated incidence of less than 3%.4 The mucosa can also be involved in DRESS but not to the extent seen in toxic epidermal necrolysis or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Liver and kidney involvement are two of the more commonly seen visceral organ manifestations in cases of DRESS syndrome. Liver injury in DRESS is not limited to one modality and can present as cholestatic, hepatocellular, or both. A cholestatic pattern of injury is the most common and is present in 37% of cases involving liver injury.5 A hepatocellular pattern of injury, which our patient experienced, is the least common and seen in approximately 19% of patients with hepatic involvement.5 Transaminase elevation is generally mild and of short duration but can reach levels as high as tenfold the normal ranges. Although acute liver failure is rarely encountered, liver transplantation can be required in severe cases. Fortunately, the patient in this case did not experience any long-term hepatic dysfunction, and his transaminases quickly corrected to normal values.

As with other organ involvement, the degree of renal injury in DRESS varies and can be as mild as proteinuria or as severe as renal failure. Acute interstitial nephritis was present in this case and is seen in anywhere from 10% to 30% of DRESS cases. Thankfully, less than 10% of patients progress to acute renal failure with only 3% needing either short or long-term dialysis.6

A urine protein to creatine ratio may have aided in the workup of renal pathology associated with our case of DRESS syndrome, however, quantitative urinalysis measurements were not captured during hospitalization. A single urinalysis collected early in the course of illness demonstrated a white blood cell count of 0-5 per hpf. This could explain why a differential of white blood cells on urinalysis was not collected. This may have revealed the presence of eosinophils on urinalysis, thus aiding in the diagnosis of interstitial nephritis.

Another case report investigating allopurinol-induced DRESS syndrome found eosinophilic tubulointerstitial nephritis and necrotizing vasculitis of the intralobular arteries without systemic markers of vasculitis. While our subject’s histology did not exhibit necrotizing features, our renal biopsy also demonstrated new tubulointerstitial nephritis with eosinophilic infiltration, similar to this case of AKI observed in a patient experiencing DRESS syndrome related to allopurinol use.7

The RIFLE (Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss of kidney function, and End-stage kidney disease) criteria are commonly used to define and stratify the severity of AKI. Metrics of classification are based on a decline in renal function. Compared to values obtained on first hospital admission, our patient met the following criteria: rise in serum creatinine >3 times the initial value, >75% decline in eGFR, and anuria persisting greater than 12 hours. Creatinine was 1.50 mg/dL on initial presentation with acute elevation to 1.89 within 24 hours, eventually reaching a peak of 7.58 mg/dL over the course of hospitalization. This demonstrates a rise in serum creatinine >5 times the value recorded at the initial presentation. Additionally, eGFR at the time of initial presentation was 66 mL/min/1.73m2, and fell to a nidus of 9 mL/min/1.73m2, reflecting an 86% decrease in eGFR. While urine output was not recorded until later in the course of hospitalization, the patient complained of an extended episode of anuria during the time of acutely rising creatinine, which persisted for greater than 24 hours. This warranted a RIFLE classification of “renal failure”.

Similarly, the Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) classification system is used for staging of Acute Kidney Injury (AKI). According to AKIN criteria, the patient must meet one of the following criteria over a 48-hour period to qualify as AKI:

-

Absolute increase in serum creatinine ≥0.3 mg/dL.

-

Increase in serum creatinine >1.5 x above baseline

-

Oliguria (urine output <0.5 mL/kg/hr for >6 hours)

Creatinine increased 0.39 mg/dL (from 1.50 to 1.89) within a 48-hour period.

AKI severity is determined based on metrics of serum creatinine and urine output. Our patient met the criteria for an increase in serum creatinine >4.0 mg/dL with an acute increase >0.5 mg/dL as described above (creatinine was 1.50 mg/dL on initial presentation with acute elevation to 1.89 within 24 hours, eventually reaching a peak of 7.58 mg/dL). Criteria for urine output was also met, as the patient experienced anuria for >12 hours. According to these findings, our patient was stratified as AKIN Stage 3.

Although not present in the patient discussed in this case, pulmonary and cardiac involvement also commonly occurs with DRESS syndrome. Shortness of breath and dry cough occur in up to 30% of patients due to pulmonary conditions such as pleuritis, acute interstitial pneumonitis, and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia.4 Patients can also develop acute respiratory distress syndrome which further increases their risk of mortality. Chest imaging via radiographs and CT’s is useful in demonstrating infiltrates and effusions in affected patients and can be used as a trending tool. As many as 21% of patients suffering from DRESS also experience cardiac involvement which can be seen in the acute phase as either hypersensitivity myocarditis or its more progressed and severe form, acute necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis.7 While any cardiac involvement in DRESS syndrome is associated with a poor prognosis, acute necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis is the worst manifestation with symptoms that include acute heart failure and cardiogenic shock and a median survival time of 3 to 4 days.8 Hypersensitivity myocarditis, also known as acute eosinophilic myocarditis, is milder in presentation and can be asymptomatic or have non-specific symptoms such as chest pain, dyspnea, hypotension, and tachycardia.

Involvement of other organ systems is seen more sparingly in DRESS. The nervous system, for example, is not commonly affected, but its manifestations can be as serious as encephalitis or aseptic meningitis. Gastrointestinal tract involvement is also uncommon in DRESS syndrome but presented in this case as persistent colitis with positive C-ANCA titers that led to a workup for autoimmune colitis, specifically ulcerative colitis. Other gastrointestinal manifestations can include bleeding, cholecystitis, esophagitis, gastritis, pancreatitis, and perforation.9 Other organs that have not been previously mentioned are rarely involved in DRESS syndrome, however, healthcare providers must be careful not to overlook such presentations during patients’ initial admission or throughout their follow-up.

In conclusion, being able to quickly recognize DRESS and discontinue the causative drug, evaluate patients for all possible manifestations, and initiate treatment in a timely manner is imperative for clinicians to reduce patient mortality and morbidity. Cases in which cessation of the offending pharmacological agent and initiation of treatment are delayed have a higher likelihood of significant organ damage and/or death. Providers also have the capacity to play a crucial role in the prevention of DRESS syndrome by limiting the prescribing of high-risk medications which include allopurinol, aromatic antiepileptic drugs, sulfonamides, vancomycin, antituberculosis drugs, minocycline, mexiletine, and nevirapine.4 After experiencing DRESS, patients should be counseled on the absolute avoidance of the causative drug as well as other drugs that have cross-sensitivity or cross-reactivity. Providers should also encourage patients to instruct their family members to avoid drugs that have caused DRESS as there is a higher likelihood that direct family members share the same drug sensitivity. As we continue to learn and understand more about the genetic component of DRESS, screening for human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles that are known to be associated with severe drug reactions has shown potential in helping to reduce the incidence of DRESS syndrome.10 Hopefully, technology can grant us better insight into the workings of DRESS and how best to avoid it altogether.

Informed Consent

The patient provided informed consent for the publication of this case report and the capture and use of images contained within.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have nothing to disclose.