Introduction

Awake craniotomy allows the removal of brain lesions to minimize the damage to the brain’s eloquent area. The eloquent area of the brain is a term that refers to the functional areas that control speech, motor, and sensory functions. Other benefits of awake craniotomy include prolonging patients’ survival, reducing the postoperative neurological dysfunction, reducing the duration of hospital stay, lowering the cost of healthcare, and decreasing incidence of postoperative complications including pain, nausea, and vomiting.1 Anesthetic management of awake craniotomy depends on the patient’s condition, pathology, the experience of the surgeon, and the duration of surgery.2 These procedures are very challenging, and the outcome depends on the teamwork of the neurosurgeon, anesthesiologist, neurologist, and ancillary team. This article will discuss ten facts about awake craniotomy.

-

In ancient history, the concept of awake craniotomy existed even before the idea of anesthesia. In the past, early medical professionals performed awake brain procedures to relieve the evil air to treat seizures and other brain conditions by trephination of the skull. The first awake craniotomy for seizures was documented in the 17th century. During the 19th century, electrical brain mapping was introduced to localize functional areas for epilepsy surgery and brain tumor patients.3

-

The word awake craniotomy is misleading for the patients and the general population because patients may not be fully awake during the surgical procedure. Patients will be asleep during the parts of intense surgical stimulus. Anesthesiologists will titrate the anesthetic medications to sedate the patients and make them comfortable. Once the brain cortex is exposed, the patient will be entirely awake for brain mapping of speech and motor areas to properly localize the pathological site and functional cortex.1

-

There are four indications for awake craniotomy. The first one is functional surgery in patients with epilepsy for excision of seizure focus with electrocorticography (ECoG) mapping of the seizure focus, and Parkinson’s disease patients for placement of deep brain stimulation (DBS) leads in the targeted areas of the brain. The second category is excision of brain tumors near the functional cortex like the speech and motor cortex. The third indication is resection of intracranial vascular lesions (Arteriovenous malformations-AVMs) that supply the functional cortex of the brain. The fourth category is minimal intracranial surgical procedures like stereotactic biopsy, brain endoscopy, ventriculostomy, and small brain lesion resections with no functional goal.4

-

The outcome of awake craniotomy depends on the patient selection with preoperative assessment by a neurosurgeon and anesthesiologist. The absolute contraindications are patient refusal, patient inability to lay still for the length of surgery, and inability to cooperate secondary to altered mental status or developmental delay. Relative contraindications are younger age, cardiorespiratory disease (including heart failure, sleep apnea, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), arthritis, learning difficulties, anxiety, and language barrier. Providing complete information to patients by explaining risks, benefits, and alternatives, neuropsychologist involvement improves the procedure’s success.

-

In the multidisciplinary approach, anesthesiologists and surgeons discuss the surgical plan and type of anesthesia, positioning of the patient, type of monitoring, and expected duration of surgery. The operating room table ensures that patients can comfortably lie in one position for an extended period. The anesthesiologist and neuropsychologist’s access to the patient is essential in a quiet room.

-

Anesthesia aims are to adequately anesthetize the patient, maintain stable intracranial pressure, and rapid return of consciousness to provide optimal surgical conditions. There are two ways of anesthesia for awake craniotomy. These include the asleep, awake, asleep (AAA) method and monitored anesthesia care (MAC). In the AAA method, the patient receives general anesthesia with an airway device such as an endotracheal tube or laryngeal mask airway; as the surgeon reaches the cerebral cortex, the patient will be awakened, and the airway device removed to facilitate the patient’s communication for brain mapping. After the resection of the brain lesion, the patient will be reanesthetized with or without an airway device. The advantages of this technique are controlling the ventilation, avoiding hypercapnia and airway obstruction. Disadvantages are the variability of patient response to general anesthesia, coughing, and straining. In the MAC method, the patient is sedated with propofol, remifentanil, or dexmedetomidine infusions to maintain spontaneous respiration. Then, 10-15 minutes before awakening, all medications are stopped. After mapping and resection of the brain lesion, the patient will be re-sedated until the completion of the surgery.4,5

-

Regional analgesia for awake craniotomy has a significant role in reducing sedation and providing patient comfort and hemodynamic stability. A scalp block is performed under sedation to block the nerves (i.e. supratrochlear, supraorbital, zygomaticotemporal, auriculotemporal, greater auricular nerve, greater and lesser occipital nerves) to provide anesthesia and analgesia. Local anesthetic infiltration or ring block by the surgeon also provides analgesia during awake craniotomy. Local anesthetic with ropivacaine or bupivacaine and with epinephrine 1:200,000 provides a longer duration of anesthesia and analgesia.

-

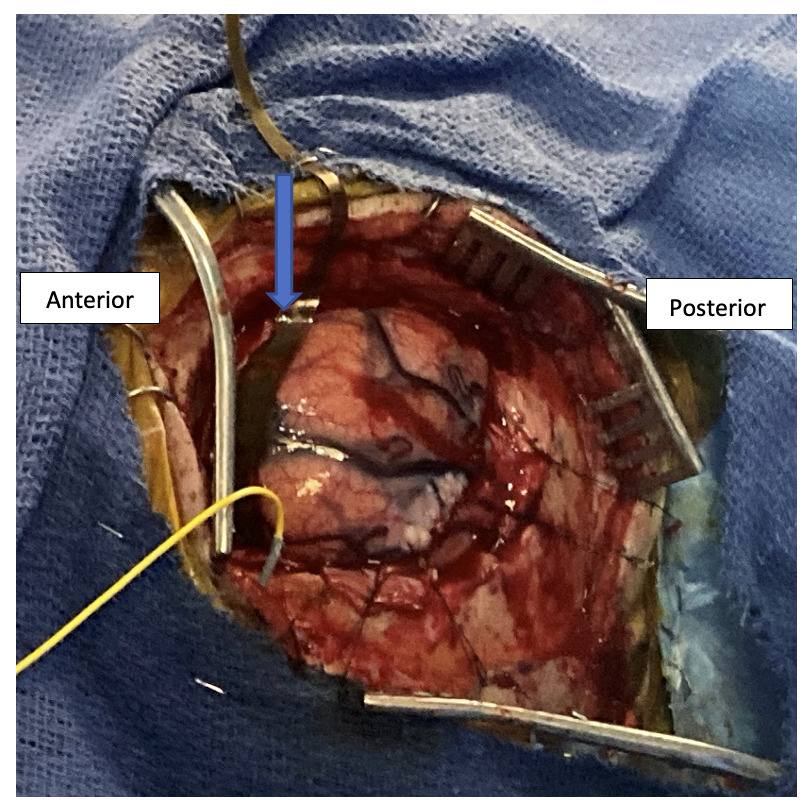

During brain mapping, team members in the operating room should be aware about the awake patient and traffic in and out of the operating room should be reduced. When the patient is awake, either an anesthesiologist or neuropsychologist communicates with the patient to localize sensory, motor, speech, and language (Broca’s and Wernicke’s area) concerning the pathological site. The surgeon communicates any changes with electrode placement in motor, speech, and language function with stimulation. A surgeon only performs resection of brain lesions after functional brain mapping is completed (Figure 1).

-

Common complications during awake craniotomy are pain from scalp pin sites, incision, discomfort related to the position, agitation, nausea, and vomiting. Major complications include airway obstruction and conversion to general anesthesia, seizures (focal/general), pulmonary aspiration, hemodynamic instability (tachycardia/bradycardia, hypotension/hypertension), local anesthetic toxicity, venous air embolism, cerebral edema and neurological deficits. Anesthesiologists should be ready to monitor and treat these conditions immediately and effectively.6–8

-

After the surgery, the patient will be transferred to intensive care unit (ICU) or postanesthesia care unit (PACU) for neurological monitoring and to observe for complications like hematoma, altered mental status, seizures and neurological deficits. Postoperatively, patients receive analgesia as nonopioid medications or oral opioids as needed.

Conclusion: An awake craniotomy is a multidisciplinary approach to improving the functional outcome of patients with intracranial lesions. Many institutions offer the awake craniotomy procedure for a broader range of indications worldwide. In the future, functional brain mapping by intraoperative MRI and new technologies will improve awake craniotomy procedures and become an appropriate choice for many intracranial surgeries (tumors, AV malformations, and functional brain surgery).