Introduction

During the first three waves of COVID-19, pediatric complications, including hospitalizations and mortality, were rare.1 When emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations among children increased during the Delta wave, however, this trend changed.2 High transmissibility has been implicated in higher rates of pediatric complications during the Delta wave.3 The emergence of a highly transmissible coronavirus variant, Omicron, underlines the urgent need to understand the impact of COVID-19 on Mississippi’s children better. Data on ED visits can be used to build baseline knowledge of trends and outcomes among children suffering from COVID-19.

Purpose

We had two main objectives. Our first objective was to examine the trend in pediatric COVID-19 ED visits and measure the length and height of each wave. Our second objective was to compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of pediatric ED visits with and without a COVID-19 diagnosis. In the latter analysis, we also sought to evaluate the predictors for emergency care among COVID-19 pediatric patients.

Methods

To investigate the epidemiology of pediatric COVID-19 ED visits, we analyzed Mississippi’s ED data. We obtained this population-level data set from the Mississippi Inpatient/Outpatient Discharge Data System. This data system compiles hospital-level data from all non-federal hospitals in the state. In Mississippi, such data are collected quarterly and released approximately three months after the end of each quarter. Included in the ED data set are variables for demographics, residence, clinical diagnoses, performed procedures, hospital charges, and outcomes of care (e.g., discharge status).

This was a retrospective analysis of Mississippi’s pediatric ED visits related to COVID-19 that occurred between 04/01/2020 and 09/30/2021. We used the latest available data; therefore, our study period ends in September 2021. In our study, we included patients between the ages of 0-18. We performed two types of statistical analyses: trend analysis and comparative analysis. To construct a trendline of pediatric COVID-19 ED visits, we compiled a data set of all pediatric patients including both Mississippi residents and non-residents. For the comparative analysis of patient characteristics, however, we restricted the data to state residents only. This restriction was needed because one of our main outcomes of interest was the in-state geographic distribution of such visits. To select COVID-19 cases, we used the following International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes: U07.1 (COVID-19), J12.82 (pneumonia due to coronavirus disease), and M35.81(multisystem inflammatory syndrome). Included in the study were patients with a primary COVID-19 diagnosis only. To evaluate the comorbidity status of the population studied, we applied the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index developed by the Agency for Healthcare Utilization and Research.4 For analyses of geographic variations, we categorized residence status by using the National Center for Health Statistics’ urban/rural classification scheme.5

We performed descriptive and inferential statistical analyses with SAS 9.4. Since hospital data fluctuate, we used the seven-day simple moving average to generate a smooth trendline for daily COVID-19 ED visits among children. Furthermore, we compartmentalized the trendline into waves and baseline intervals to gauge the surges in pediatric COVID-19 ED visits. We used the following approach to identify the length of each wave. We stratified the trendline into time series of seven days. If the seven-day moving average increased/decreased by at least 20% compared to the previous seven-day period, we marked the beginning and end of each wave.

The variability in waves was assessed by using the interquartile range and boxplots charts. Demographic and clinical characteristics between COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients were compared with chi-square tests. We also performed comparative subgroup analyses of the comorbidity burden between different demographic groups within the COVID-19 cohort. Finally, we applied a multivariable logistic regression model to predict demographic risk factors for COVID-19 ED visits. The covariates included in the model were age, gender, race, residence, and payer as a proxy for socioeconomic status. We conducted analysis on racial distribution, but not on ethnicity due to a small number of children with Hispanic ethnicity in our study population.

Results

From the beginning of April 2020 through the end of September 2021, there were 9,261 pediatric ED visits with a primary COVID-19 diagnosis in Mississippi. This number represents 94.0% of all COVID-19 ED visits (i.e., visits with a primary and secondary diagnosis for this disease). Of the total 9,261 COVID-19-related visits, 8,954 (96.7%) were among state residents. The majority (59.7%) of such visits occurred during the Delta wave, while 19.4% were recorded during the third and 7.2% were recorded during the second wave. The rest of the pediatric ED visits (13.7%) occurred in the periods between the waves.

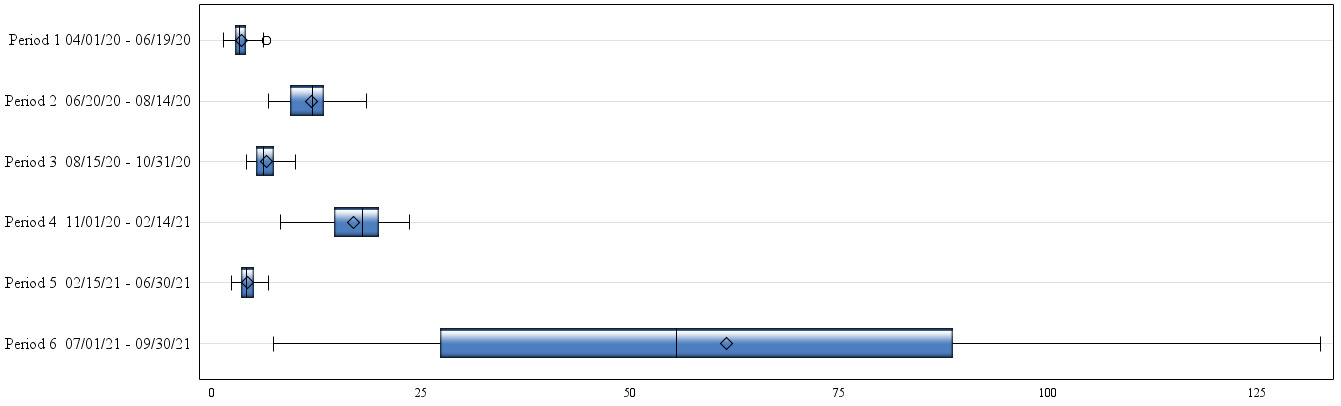

The first COVID-19 wave among the pediatric population was not clearly visible, but all consecutive waves were well defined. The second wave of COVID-19 ED pediatric visits peaked in mid-July 2020; the third wave crested at the end of November 2020; and the fourth wave (Delta) reached its highest point in mid-August 2020 (Figure 1A). The second wave lasted for nearly two months (55 days), while the third wave was taller and longer, persisting for over three months (105 days). The third wave also demonstrated two dips in its course: these depressions in the trendline occurred around Thanksgiving and Christmas when there was less health care utilization in general. Like the third wave, the duration of the fourth wave (Delta) was about three months (92 days). However, the Delta surges was much higher than the previous two COVID-19 surges, reaching 133 pediatric emergency visits per day at its peak. By contrast, the maximum number of visits was 18 per day during the second wave and 24 during the third wave.

The measures of central tendency and variability of the time series is visualized in Figure 1B with boxplots. In this graph, boxes contain 50% of the data (e.g., the interquartile range between 25th and 75th percentiles), while whiskers denote the minimum and maximum data points. Inside the box, the horizontal line represents the median and the diamond-shaped figure pinpoints the mean value of the time series. According to this analysis, the median daily number for pediatric COVID-19 ED visits and interquartile range (IQR) were 12.0 (9.4 to 13.4) during the second wave; 17.9 (14.6 to 20.0) during the third wave; and 55.6 (27.3 to 88.7) during Delta. Between the waves, the median daily number of pediatric COVID-19 ED visits was 3.2 (from 2.7 to 4.1).

Regarding ED utilization by hospital size, medium-size and small hospitals provided most of the pediatric COVID-19 emergency care during the study period. Large facilities accounted for 37.1% of all pediatric COVID-19 visits, while medium-size facilities accounted for 35.8% and small hospitals for 27.1% of all such encounters (Table 1).

In terms of demographics, among state residents who sought pediatric emergency care for COVID-19, 64.7% were African Americans, 59.0% lived in non-urban areas, 50.6% were in the 0-11 age group, and 53.5% were females (Table 1). Compared to all other pediatric patients, those with a COVID-19 diagnosis were more likely to be African Americans (64.7% vs. 55.6%), older children (49.4% vs. 34.9%, p <0.001), and females (53.5% vs. 50.5%, p < 0.001).

To evaluate the socioeconomic status of the study population, we analyzed payer data. This analysis showed that Medicaid, the insurer of the low-income population, was a major payer for pediatric ED visits in general. This insurance group covered 73.0% of all ED visits during the study period, including COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients (Table 1). Compared to non-COVID-19 ED visits, the proportion of Medicaid-covered COVID-19 ED visits was slightly but still statistically significantly higher (77.9% vs. 72.9%, p < 0.001). Among the 6,973 pediatric COVID-19 ED visits covered by Medicaid, 4,794 (68.8%) were African Americans and 4,172 (59.8%) were non-urban residents.

The comorbidity analysis revealed that 12.0% of the study population, COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients, had at least one coexisting illness. The comorbidity burden, however, was equally distributed among children with and without a COVID-19 diagnosis (11.6% vs. 12.0%, p = 0.220). From the studied comorbidity list, the most frequent comorbidities among the pediatric population in need of emergency care was asthma. But this condition, was only slightly lightly more prevalent among the COVID-19 study group (5.7% vs. 5.0%, p = 0.023). Regarding acute complications, fluid and electrolyte disorders (e.g., dehydration) were also more frequent among the COVID-19 cohort (3.8% vs. 1.1%, p < 0.001). The proportion of pneumonia was similar for the non-COVID-19 and COVID-19 group.

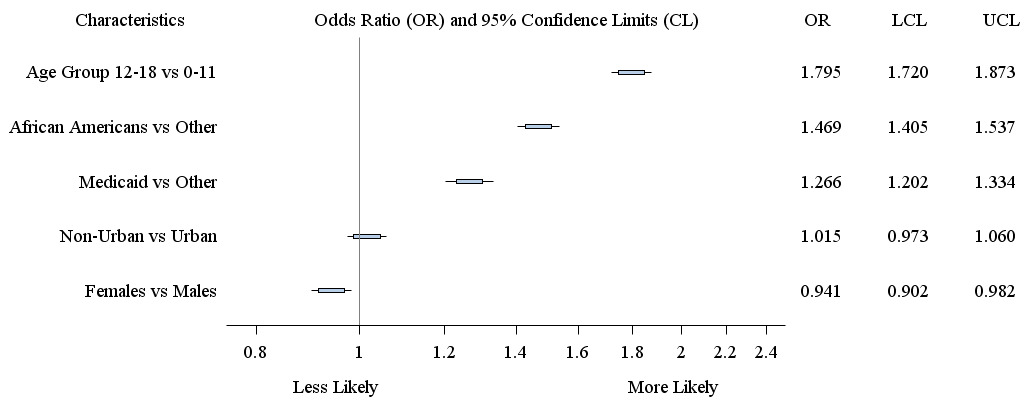

Predictors of COVID-19 pediatric visits were assessed by multivariable regression that incorporated all of the above-mentioned demographic factors. The multivariable regression model uncovered that the strongest predictor for COVID-19 ED visits was older age (OR, 1.80 95% CI, 1.72-1.87), followed by African American race (OR, 1.50 95% CI, 1.41-1.54), and Medicaid insurance status (OR, 1.27 95% CI, 1.20-1.33) (Figure 2).

Presented in Table 2 is the comorbidity sub-analysis for the COVID-19 cohort. According to this analysis, non-urban COVID-19 pediatric patients had a higher comorbidity burden than their urban counterparts (13.3% vs. 10.3%, p < .001). The same was true for older children compared to younger children (15.0% vs. 8.2%, p < .001). The prevalence of comorbidities was higher among Caucasians and male children, but these differences were not statistically significant.

Discussion

In this study, we described and measured the first four waves of the COVID-19 pandemic among the pediatric population in Mississippi. There was not a discernable first wave among the pediatric population, but this trend changed as the pandemic unfolded. A poorly defined first wave in ED visits represented low COVID-19 incidence among children. The same pattern was noted nationwide and associated with school closure.6 In Mississippi, the first COVID-19 positive case was reported on 03/11/2020.7 To prevent transmission of this novel virus, all public schools were closed on 03/19/2020 and a “shelter-at-place” order was issued on 04/01/2020.8,9 The low incidence of pediatric COVID-19 complications at the start of the pandemic signifies the importance, effectiveness, and timeliness of these mitigation measures for containing the viral spread. At the same time, the initial lack of severe pediatric cases contributed to an early underestimation of pediatric COVID-19-related complications.

Demographic analysis of the studied population uncovered two significant issues. The first issue was related to the pattern of pediatric care. During the study period, almost two-thirds of all ED pediatric visits in the state were covered by Medicaid. This pattern of care preceded the COVID-19 era and worsened during the pandemic. Medicaid coverage was even higher in children with COVID-19 as compared to the already high baseline emergency care utilization rate. Overutilization of Mississippi’s emergency department as a substitute for primary pediatric care should not be surprising, however. The lack of primary care access for Medicaid patients has been an area of long-standing—albeit unsettled—national discussion.10 In Mississippi, this concern runs even deeper; in our state, 56.1% of the pediatric population is served by Medicaid as compared to the national average of 37.5%.11

The second issue uncovered by our analysis was the importance of race and residence in determining the pattern of pediatric emergency care for COVID-19. African American children and non-urban children had a significantly higher prevalence of COVID-19 ED visits—a finding that points to key demographic disparities in the overall COVID-19 patient population. African Americans accounted for 66.9% and non-urban residents for 62.0% of all pediatric COVID-19 ED visits. It is worth noting that Medicaid-covered COVID-19 visits exhibited the same racial and residence-based disparities with African Americans (72.5%) and non-urban residents (62.4%) comprising the vast majority of patients. These findings exemplify the complex entanglement of socioeconomic, demographic, and health factors. It is often difficult to isolate the impact of individual demographic or social factors on health outcomes. Based on our data, we can only speculate on the drivers for these disparities. What we know with certainty is that over one-quarter (27.6%) of Mississippi’s children live below the federal poverty level, and more than half of the pediatric population relies on Medicaid.12 As our research suggests, the COVID-19 pandemic only exacerbated Mississippi’s deep and preexisting health inequalities.

Public Health Implications

Defining the scope of a public health issue is a prerequisite for developing effective strategies. The fact that we are still amid the COVID-19 pandemic and its fifth wave only underscores the importance of building long-term preventive policies based on data and evidence. Since COVID-19 hospitalizations are rare among the pediatric population, ED data is one of the most relevant data sources to study the COVID-19 impact on children. Our research accomplished two important goals from a public health perspective. First, we were able to establish a baseline number for daily COVID-19 pediatric ED visits. As COVID-19 transitions from pandemic to endemic, changes in such baseline data can be used as an early-warning indicator during future waves or seasonal surges. Second, our study uncovered a high prevalence rate in the state of COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 pediatric emergency care use among Medicaid patients. This finding suggests that a significant proportion of the children and adolescents who receive emergency care for COVID-19 are from lower income households and may lack primary pediatric care. Our study should serve as a call to action to promote dissemination of such evidence-based information and to advance effective public health strategies. Examples for such successful public health strides are increasing vaccination rates and improving access to primary pediatric care.