Introduction

Traumatic injuries are a leading cause of death and severe disability for young adults in the United States, including Mississippi.1 Globally, trauma remains the third leading cause of mortality, with 5 million deaths per year.2 The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in “shut-down” and “stay at home” orders globally that had debilitating effects on the economy and health care system in general. The U.S. Census Bureau reveals a disproportionate burden of multiple economic and social stressors within Mississippi throughout this time. These stressors may have contributed to the increased burden of trauma.3 They include a loss of employment income, food scarcity, delayed medical care, housing insecurity, childcare disruptions and difficulty paying for basic household expenses.3

Other studies, nationally and globally, have reported an overall decline in traumatic injuries during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic.1,4–42 This trend generally parallels the decline in emergency medical services (EMS), emergency department visits, trauma activations and acute care surgical encounters in hospitals across the U.S. that were facing multiple additional challenges in caring for sick patients with COVID-19.43–46 Despite reports of an overall decline in traumatic injuries during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the majority of U.S. studies on this topic also report a proportional increase in penetrating trauma, primarily gunshot wounds.36

As the only Level I trauma center in Mississippi, a significant number of critically injured trauma patients within Mississippi are treated at our institution. This study aims to describe the trends of traumatic injuries during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic within our institution. We also compare these findings to the one-year timeframe preceding the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We obtained approval for this study from our Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC). The IRB approved a waiver of informed consent because we utilized de-identified data within the University of Mississippi Medical Center Trauma Registry. This Registry includes all trauma patients who present to the UMMC emergency department and meet injury criteria for a trauma activation. This includes scene transfer and “walk-in” patients as well as interfacility transfers by ground or helicopter medical personnel. We performed a retrospective review of the Trauma Registry for individuals aged 16 years and older who sustained a traumatic injury and required a trauma team evaluation at UMMC from April 1, 2018, to March 31, 2021. The study period included the two years prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The two “pre-COVID periods” were April 1, 2018, to March 31, 2019 (T1) and April 1, 2019, to March 31, 2020 (T2). The “COVID period” (T3) began on April 1, 2020, the onset of our Mississippi stay-at-home order, and continued until March 31, 2021.

According to the UMMC Trauma Registry data, all patients are classified by trauma type: blunt, penetrating, burn and unclassified. Additional demographic data such as age, sex, race, mechanism, injury severity score (ISS), mortality, level of activation and discharge status (home, rehabilitation, morgue) were obtained. We have three trauma activation levels at UMMC. They are categorized as “Alpha,” “Bravo,” or “Charlie,” with specific injury criteria for each designation. An “Alpha” activation is reserved for the most critically ill patients with traumatic injuries. “Bravo” and “Charlie” activations, in descending order of potential severity, meet injury criteria for less severe trauma.

We evaluated the registered zip code of residence for each person within the study timeframe to determine a Distressed Community Index (DCI). The DCI incorporates multiple metrics to calculate an overall marker of economic well-being for every zip code within the United States.47 This facilitates an estimation of overall economic well-being for each patient within our registry timeframe.

As part of our background research, we conducted a search in PubMed and discovered multiple similar U.S. and international studies examining the overall incidence and breakdown of traumatic injuries during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic.1,4–42 Descriptive statistics were utilized throughout the study. No inferential statistics were compiled, and no statistical models were constructed within this study. Simple counts and percentages changed across relevant categories and were represented by stacked bar charts and numbers displayed. All analyses were completed with Stata v17.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

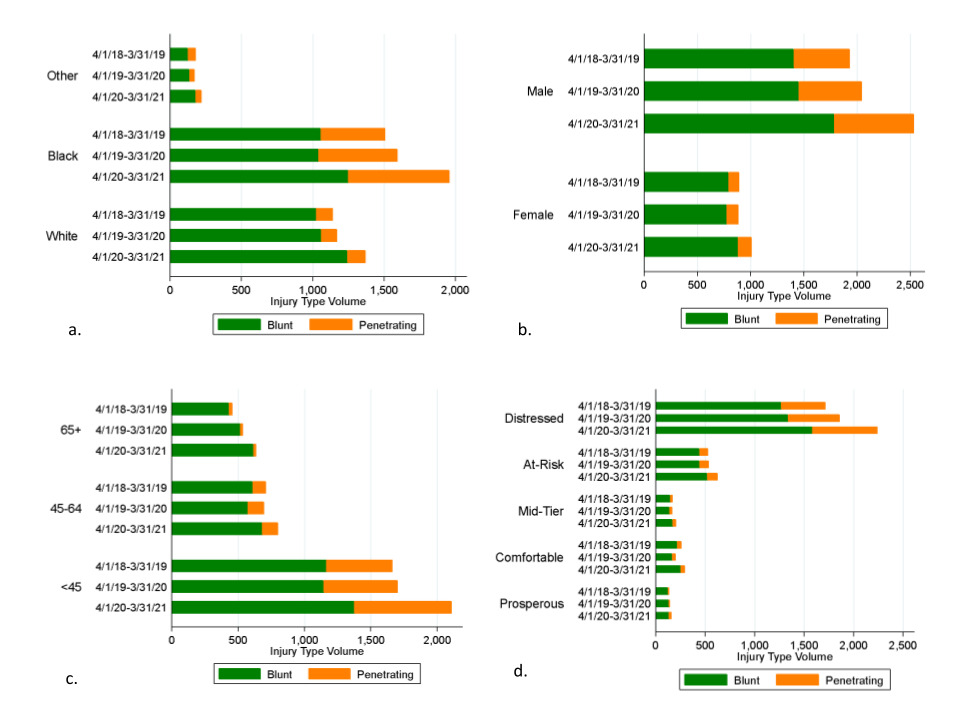

Overall, the trauma volume includes 2,841 persons in T1 (2,202 blunt, 624 penetrating, 9 burns, 6 unclassified), 3,024 persons in T2 (2,232 blunt, 699 penetrating, 6 burns, 87 unclassified), and 3,580 persons in T3 (2,670 blunt, 873 penetrating, 11 burns, 26 unclassified). This corresponds to a 6% overall increase in trauma from T1 to T2, with a 4% increase in combined blunt and penetrating trauma (1% increase blunt, 12% increase penetrating). There was an 18% overall increase in trauma from T2 to T3. However, once we excluded burns and unclassified mechanism of injury, there was a 21% increase in overall trauma from T2 to T3 (20% increase blunt, 25% increase penetrating) (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

There was an increase in blunt trauma across all subgroups during the COVID period (T3). Blacks had a 20% increase in blunt trauma compared to Whites, with a 18% increase. This compares to a 2% decrease in blunt trauma for Blacks and a 3% increase in for Whites in the pre-COVID timeframe (T2). Males had a 23% increase in blunt trauma while females had a 14% increase compared to a 3% increase and 2% decrease in blunt trauma for males and females respectively in T2. Individuals of all ages had a 19% to 20% increase in blunt trauma in T3. However, most of the injuries were among the 16-45 age group.

During the COVID timeframe (T3), Blacks had more penetrating injuries, with 551 in T2 and 708 in T3 (28% increase), compared to Whites, with 112 in T2 and 126 in T3 (13% increase). Males also had more penetrating injuries, 590 in T2 and 126 in T3 (26% increase). Individuals aged 16-45 years had more penetrating injuries during the first year of the pandemic compared to other age groups: 558 in T2 and 733 in T3 (31% increase). Among the 65 and older age group, penetrating injuries remained stable, although absolute numbers for this group increased.

In the sub-group analysis of blunt injuries utilizing DCI, “distressed” had 1337 in T2 and 1580 in T3 (18% increase), “at risk” had 440 in T2 and 519 in T3 (18% increase), “mid-tier” had 137 in T2 and 169 in T3 (23% increase) and “comfortable” had 164 in T2 and 252 in T3 (54% increase). The “prosperous” group was the only cohort with no change in the incidence of blunt injuries during the COVID period. In the DCI subgroup analysis, individuals with greater markers of economic distress had a higher incidence of penetrating injuries as well. In the “distressed” group, there were 520 in T2 and 661 in T3 (27% increase). In the “at risk” group, there were 95 in T2 and 105 in T3 (11% increase). In the “comfortable” group, there were 36 in T2 and 42 in T3 (17% increase). In the “prosperous” group, there was a 136% increase in penetrating injuries (Figure 3). However, the “prosperous” group had the smallest sample size within this sub-analysis compared to individuals in the “distressed” group (26 compared to 661).

Discussion

This study reports an 18% increase in trauma volume at our hospital during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to a 6% increase in the previous year (pre-COVID). This increase was seen in both penetrating and blunt trauma during the study period and was inclusive of the stay-at-home period within our state. Our findings contrast with many contemporary studies on this subject, which report an overall decline in traumatic injuries during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly during the period of stay-at-home orders.1,4–42 According to most studies on this topic, many trauma centers experienced an increase in traumatic injuries after the lifting of stay-at-home orders. In contrast, our medical center experienced a marked increase in traumatic injuries during the period of stay-at-home orders and during the period when stay-at-home orders were lifted.

In their article, Talev describes the disproportionate economic strain of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. when stating “The coronavirus is spreading a dangerous strain on inequality. Better-off Americans are still getting paid and are free to work from home, while the poor are either forced to risk going out to work or lose their jobs.”48 This economic reality hit Mississippians particularly hard during the COVID-19 pandemic and may be one of several factors that have contributed to the disproportionate burden of trauma during this period within our state, particularly on young, black males from economically depressed areas. This scenario is potentially devastating because victims of trauma may often survive their traumatic event but endure severe disability and years of lost wages, thus perpetuating the cycle of poverty.

There are several factors that may contribute to the increased burden of trauma within our facility during this time. Some drivers of persistent, violence-related injury, despite shelter-in-place, may include increased financial insecurity, psychosocial stressors and decreased access to health and social services, all prevalent during the COVID-19 pandemic.10 In their book, The Locust Effect, Gary Haugen and Victor Boutros describe the disproportionate and devastating effects of trauma on impoverished individuals and communities in the developing world.49 A large body of global literature links economic insecurity to multiple types of traumatic injury. While much of this evidence is correlational, it suggests that economically insecure populations tend to live in locations with weaker access to health and other support services. They are also more likely to live in economically depressed areas, often with higher rates of crime.50,51 Mississippi frequently scores last in our nation in areas such as poverty, joblessness, access to healthcare and quality education,48 and our study demonstrates that individuals in distressed communities have a higher percentage of traumatic injuries.

There are several limiting factors within our study. Namely, this study was a retrospective review of data from a single, institutional trauma registry. In addition, our state trauma system may facilitate transfer of critically injured trauma patients within the northern or coastal regions of Mississippi to a closer Level I trauma center in either Memphis, Tennessee or Mobile, Alabama. Our data does not examine the results of these out-of-state transfers during this timeframe. There are multiple trauma centers within our state that are designated as Level II, III or IV, and our institutional registry does not capture the number of trauma patients treated at any of these facilities unless they were transferred to our facility for further care. Despite the overall limitations of this study, the results of our data during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic may offer helpful insight into the increased burden of trauma at the only Level 1 trauma center in our state during this challenging time.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates an overall increase in traumatic injuries at our only Level 1 trauma center in Mississippi during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, predominantly among young, black males and persons from economically distressed communities. This finding signals a need for greater collaborative research to closely examine the socioeconomic and other stressors that accelerate the burden of trauma during heightened times of distress such as the COVID-19 pandemic. This collaboration may also serve to create better programs and innovative measures to reduce and improve these disparities going forward.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Mrs. Amber Kyle, Director of Trauma Services at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, for her knowledge and expertise about the Trauma Registry at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. She also assisted us with obtaining key data from this Registry, upon study approval by our Institutional Review Board. In addition, Mrs. Kyle provided helpful guidance in the planning and study design of this project.