Introduction

Our patient was diagnosed with bacteremia caused by Escherichia albertii, a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic bacillus. This pathogen was first identified in the blood of a 9-month-old with diarrhea in Bangladesh, classified as Hafnia alvei. The isolated strains were similar to enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli.

E. albertii has been implicated as an etiologic agent of disease in domestic and migratory birds. Studies have shown that strains can be both food- and waterborne. There have been strains isolated from chickens, processed meats such as pork, duck, mutton, and contaminated water. As for our patient, we are unsure if she encountered any animal or animal product that may have caused her to contract this pathogen.1

According to the literature, there have been two previous cases of E albertii bacteremia reported. Both patients had multiple comorbidities and were treated with piperacillin/tazobactam for three days. After learning of this treatment and discovering our patient was positive for E. albertii bacteremia, she was switched to piperacillin/tazobactam.

Case Presentation

A 32-year-old female with a history of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, heavy alcohol and tobacco use, presented with a chief complaint of dysuria and abdominal pain for two days before arriving at an outside hospital (OSH). Due to the patient having a history of alcohol use, it was advised that she stay for treatment. She left against medical advice (AMA) despite being told she should not drive. There were no laboratory reports at OSH for her blood alcohol content. After leaving the hospital, she began to have progressive back pain for the next few days along with subjective fevers, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and a pounding headache. She returned to the initial hospital 2 days later and was diagnosed with a urinary tract infection (UTI) and was found to be hypotensive. She was started on ceftriaxone and vancomycin, given three liters of normal saline, and transferred to our hospital for further evaluation.

She had no relevant medical history apart from previously indicated and was not on any medication at the time of admission. She reports heavy alcohol use, stating she drinks a case (24 cans) of beer daily, “until I blackout.” She reports smoking one pack a day of cigarettes.

Clinical Findings

Upon arrival at the outside hospital (OSH), the patient’s initial vital signs included a blood pressure of 102/52 mmHg, heart rate of 93 beats per minute, temperature of 102.3°F, and an oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. Initial laboratory results revealed a white blood cell count of 11.2 K/uL, hemoglobin level of 6.9 g/dL, and platelet count of 113 K/uL. The chemistry panel demonstrated a sodium concentration of 122 mmol/L, potassium of 3.2 mmol/L, bicarbonate of 20 mmol/L, and a blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio of 18.7. The glucose level was 320 mg/dL, with a lactic acid measurement of 4.5 mmol/L. Beta hCG testing was negative.

Upon arrival at our hospital, labs were repeated along with blood cultures. On physical examination, the patient appeared to be her stated age, in no acute distress. She was alert and oriented to person, place, and time. She had no scleral icterus. She was tachycardic but no murmurs, rubs, or gallops were heard. She had good distal pulses. Breath sounds were clear bilaterally. There was mild suprapubic tenderness but no distension or guarding. There were no rashes or jaundice seen. She continued to be anemic with a Hgb of 6.6 g/dL, requiring a unit of packed red blood cells. She was continued on ceftriaxone for possible acute cystitis.

CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis demonstrated hepatomegaly, mild hepatic steatosis, and a complex R adnexal mass containing fat and solid components, suggesting ovarian dermoid.

Following the patient’s abdominal CT scan at an outside hospital, an abdominal ultrasound was performed, which demonstrated cholelithiasis with a positive Murphy sign along with hepatic steatosis; the radiologist recommended a hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan. The HIDA scan confirmed acute cholelithiasis, and surgical consultation was obtained to evaluate for possible cholecystectomy. (See Figure 1)

During this time, her blood culture was reported as gram-negative bacilli (GNB). Due to the most common causes of gram-negative bacteremia, we continued her on ceftriaxone.

On Day 3 of admission, she was scheduled for her laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Before surgery, her blood culture resulted in Escherichia albertii. After reviewing the literature and discussing the results with the team, it was decided to discontinue ceftriaxone, and she was started on piperacillin/tazobactam. She tolerated the surgery well, but, due to respiratory failure, she remained intubated and moved to our Critical Care Unit (CCU) for a higher level of treatment. Her urine culture had insignificant growth. Repeat blood cultures were collected, which resulted in no growth after 5 days.

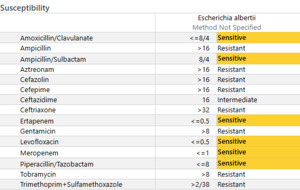

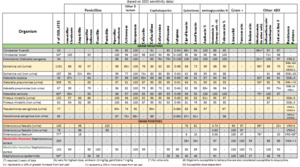

On Day 4 of admission, susceptibilities for the blood culture resulted. (See Figure 2) According to our Microscan AST, E. albertii was sensitive to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, amoxicillin/sulbactam, ertapenem, levofloxacin, meropenem, and piperacillin/tazobactam. This GNB was resistant to cefazolin, cefepime, ceftazidime, and ceftriaxone. She continued to use piperacillin/tazobactam. She was also successfully extubated on this day, moved to a nasal cannula, and transferred back to the floor.

She continued to improve and was discharged on Day 6 with Augmentin 875-125 TID to complete a 14-day course.

Discussion

Escherichia albertii is an emerging foodborne enteropathogen that can cause diarrhea, abdominal distension, fever, vomiting, and bacteremia. Our patient stated she was having diarrhea along with nausea and vomiting. She also complained of abdominal pain.

There have been two previous cases reported of Escherichia albertii bacteremia. The first recorded case was in 2015 from a 76-year-old female with multiple comorbidities. She was admitted from a residential care facility with a febrile illness of unknown cause, with a temperature of 101.6°F and was tachycardic with a heart rate in the 130s. According to the chart, the patient had no clinical features of gastrointestinal infections. Blood cultures were drawn at that time and resulted in a gram-negative bacillus. It first resulted from MALDI-TOF, taken directly from blood cultures, as E coli. The patient was started on piperacillin-tazobactam. However, there was a discrepancy when the molecular method was used to identify the pathogen. The isolate was identified as Enterobacteriaceae but was negative for E coli. It was then tested by 16S rRNA-based identification and was consistent with E albertii. 2 Awasthi SP et al. reported that when conventional end-point PCR methods are used, E. albertii is frequently misidentified as enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), or Shigella boydii because of shared biochemical characteristics and virulence factors. When quantitative real-time PCR was used, testing against 39 E. albertii strains and 36 non-E. albertii controls across 18 species, the assay achieved 100% sensitivity and specificity. 6

The second recorded case came from China with a 50-year-old male with liver cirrhosis in 2022. His chief complaints were abdominal distension, fatigue, and poor appetite. He had a similar history to our patient, with a history of alcohol abuse and tobacco use. He was diagnosed with liver cirrhosis over 2 years ago, however. He did have an abdominal MRI performed, which showed hepatomegaly, cholecystitis with inflammatory deposits, small cysts on the kidneys, and an accessory spleen. He also had a low Hgb on admission and was given one unit of pRBCs. He developed a fever during his stay, and blood cultures were drawn. After 24 hours, the cultures resulted in Gram-negative bacilli, and he was started on piperacillin/tazobactam for 3 days. The pathogen was identified as E albertii with sensitivities for all antibiotics. Compared to our patient, this patient’s strain was sensitive to ceftriaxone, but our patient’s strain was resistant to ceftriaxone.3

Bacteremia is a serious complication, and the most common causative agents are Gram-negative bacilli, e.g., E coli, Klebsiella species., Enterobacter spp. E albertii is typically found in poultry meat, wild birds, and raccoons.3 This pathogen has caused many foodborne outbreaks in Japan and has been isolated from poultry broilers in parts of the United States. 4 In a study conducted by Wang, et al., they investigated the prevalence E. albertii in broilers from farms in multiple states and isolated the bacteria from chickens. Two hundred-seventy cloacal swabs were taken from broilers from nine farms in Mississippi and Alabama. E albertii was identified in 16% of the swabs with 12 strains. The strains were then tested for antibiotic sensitivities. Most strains were resistant to aminoglycosides, with numerous showing intermediate resistance to cephalosporins of all generations. There were also strains from certain broilers that had intermediate resistance to carbapenems.

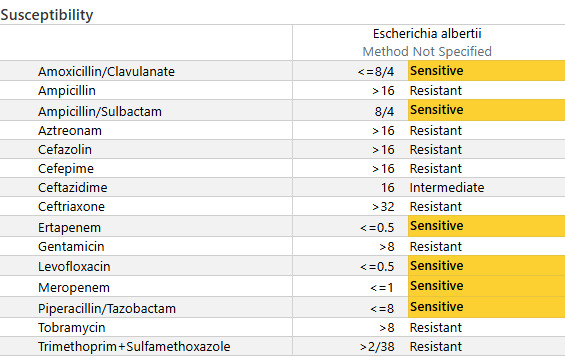

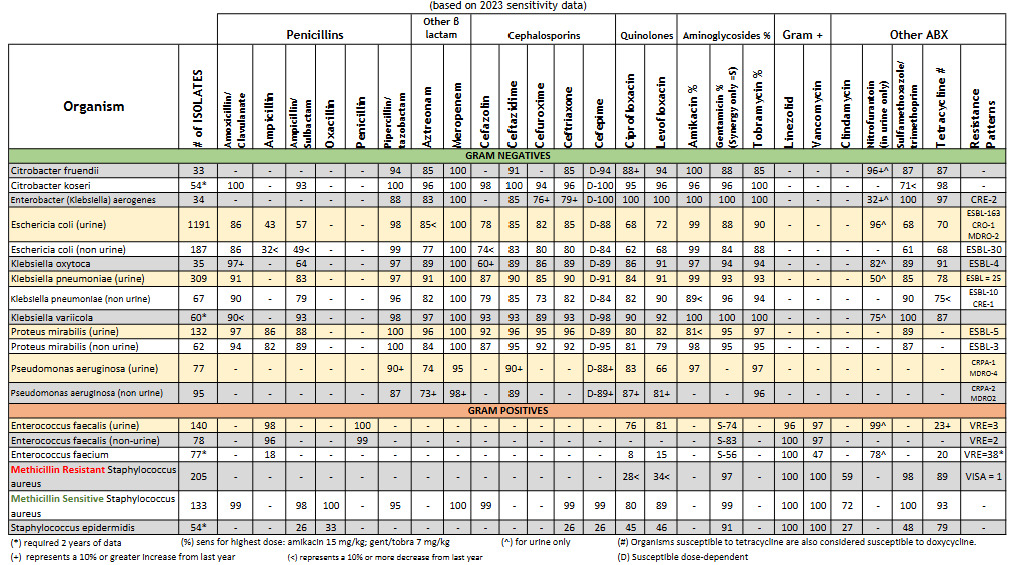

Antibiotic resistance of E. albertii isolates was a concern when compared to local sensitivities of E. coli. Resistance rates had been reported to range from 20-40% from ampicillin/sulbactam, cefepime, ceftriaxone, aztreonam, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.5 While our institution has similar ampicillin/sulbactam and ciprofloxacin resistance rates, generally, cephalosporin resistance is not a concern. (See Figure 3). This notion proved challenging in this patient, as she was not clinically improving. Before her blood culture returned positive for Gram-negative bacteriemia, our team continued to treat her as though she had a urinary tract infection; therefore, we continued with cephalosporin treatment. However, when she continued to decline, we had to assess whether this was due to antimicrobial treatment failure while awaiting susceptibilities versus a lack of source control. Other differentials for her lack of clinical improvement included the possibility of the patient experiencing withdrawal symptoms.

Conclusion

Evidence shows that this bacterium is becoming an important human and animal pathogen. It has been shown that E albertii is resistant to numerous antibiotics.1 Similar to the two previously reported cases, our patient had relatively few comorbidities; however, her immunocompromised state, related to heavy alcohol use and cholecystitis, likely impaired her ability to clear the infection. Clinicians should remain vigilant for uncommon pathogens in patients presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.