Introduction

Acromioclavicular (AC) joint injections are a relatively common primary-care procedure with both therapeutic and diagnostic benefits. The most common technique for injecting the AC joint involves palpating the superior shoulder and identifying the bony prominence, the acromion, then palpating medially to identify the clavicle. Between these two landmarks, one finds the AC joint as a soft, palpable depression in the skin. Using a standard sterile technique, a needle, often a 25ga (0.51mm), is then inserted into this space using a superior and anterior approach.1 If resistance is met, the needle is repositioned and ‘walked’ medially or laterally, until it falls smoothly through the joint capsule and into the joint space. A steroid is often mixed with a local anesthetic and then injected into the joint.

As with any joint injection, the most common complication of this procedure is pain and bleeding, and much less frequently, infection.2 Exact rates of these complications are difficult to ascertain due to heterogeneity in reporting, but one Cochrane analysis found non-serious adverse events occurred in 18.1% of shoulder injections.3 Another study found that pain alone accounted for up to 58% of the total reported adverse events, but the literature does not differentiate the specific cause of the pain (i.e. the act of piercing the skin or unintentionally pressing the needle into the bone). By contrast, infection is so rare it typically only appears in the literature as case reports.4

The width of the AC joint normally measures 1-6mm in females and 1-7mm in males. A joint width of <0.5mm may be considered normal in patients over 60 years old.5 The joint plane is typically slanted 20°–30°, with the clavicle overriding the acromion, however, there is significant variability in the degree of slant, ranging from nearly vertical to nearly horizontal.6 The small size of this joint makes it relatively difficult to access in one pass using a palpation-guided approach, which relies on landmark palpation. The act of walking the needle along the clavicle or acromion until it falls into the joint is painful for the patient. Moreover, there is no guarantee that the injectate is truly in the joint space using the palpation-guided approach.

With the advent and increasing prevalence of point of care ultrasound (POCUS), there is growing evidence that an ultrasound-guided AC joint injection achieves greater rates of intra-articular injection than does a palpation-guided approach, which relies on landmark palpation. A recent literature review demonstrated US-guided success rates ranging from 90-100%, compared to 40-70% when using a palpation-guided approach.7–9 Some studies have also shown that the accuracy of ultrasound technique was essentially the same, regardless of operator experience.10 Furthermore, most studies have used cadavers as subjects, which did not account for age, gender, or Body Mass Index (BMI). Older studies reported the age of patients receiving an injection, but do not mention whether it impacted the success of the injection.11

METHODS

The purpose of this study was to compare palpation-guided versus ultrasound-guided identification of the AC joint. Additionally, the effects of age, gender, and BMI on both techniques were also examined. Given the reported rates of accuracy using POCUS in previous studies, we used POCUS as our gold standard.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained and subjects were recruited from an academic hospital’s Emergency Room or a Primary Care Sports Medicine Clinic using convenience sampling based on the availability of the principal investigators. Subjects were not known to the investigators prior to recruitment. Exclusion criteria were then applied. Subjects with evidence of trauma to the shoulder or those who had undergone shoulder surgery within the previous twelve months were excluded. Subjects less than eighteen years old and those without decision-making capacity were also excluded. Based on these criteria, no subjects were excluded. Written consent was obtained from those patients who wished to participate in the study.

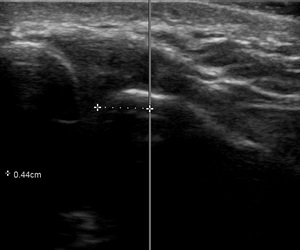

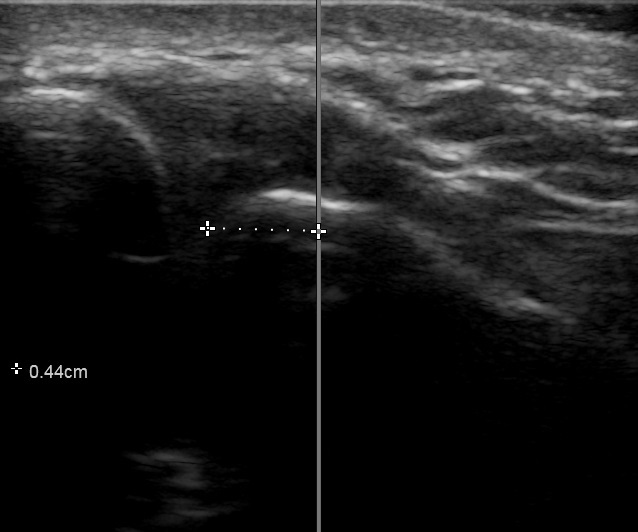

Two Primary Care Sports Medicine (PCSM) Fellows who were trained in musculoskeletal anatomy and musculoskeletal ultrasound, served as the study investigators. They were supervised by a board certified PCSM Attending Physician who is also credentialled and Registered in Musculoskeletal (RMSK) sonography. One of the study investigators was asked to identify the patient’s left and right AC joint using the palpation technique and then using a pen, mark the site through which they would insert the needle. The second PCSM Fellow then centered a Fujifilm Sonosite PX 15-4 ultrasound probe over the pen mark. The distance to the nearest border of the AC joint was measured and recorded using the ‘caliper’ function in the Sonosite software to the nearest tenth of a millimeter. The investigator’s accuracy on each shoulder was not made available to them, so there was no opportunity to adapt their approach to future subjects. One Fellow marked both shoulders of a single subject while the second Fellow only operated the POCUS on that subject.

18 subjects were enrolled in our study (AC joints, n = 36), evenly distributed by gender with 9 females and 9 males.

Descriptive statistics were compiled as appropriate. Estimated average distances were drawn from generalized estimating equations (GEE) with gamma families and exchangeable correlation structures. This strategy is required to account for repeated measures within subjects (one measure on each shoulder) and accounts for this correlation which would violate the independence assumption of a standard linear model. A binary classification was also performed on the patients based on whether the distance fell within the sex-specific radius (in mm) for the AC joint. This provided an indication of how likely the injection would be in the joint without ultrasound. This was then estimated with similar GEE models, except with Bernoulli families. Probabilities were then calculated via post-estimation integrated margins. Age, BMI, and sex were considered as potential confounders in univariate models. All statistics were calculated with R v4.1.0.

RESULTS

Among the 18 enrolled participants (n=36 AC joints), 9 identified as female and 9 as male. The age range was 22 to 65 years (M = 39.9 years, SD = 11.4 years). The BMI range was 20.4 to 54.8 (M = 32.2, SD = 9.3). In Mississippi, where this study was performed, 37.9% of the population is obese, with a BMI greater than or equal to 30.12 The average age in Mississippi is 37.5 years.13

Across all subjects, the raw mean distance from the point landmarked by the investigator compared to the nearest margin of the AC joint was 8.62mm (95% CI: (8.58-8.66)). Within-subject variation in the distance measured was minimal across shoulders (Figure 4), and neither age, gender, nor BMI had any association with the distance (p=0.373, p=0.842, p=0.431, respectively).

This led us to the analysis on the binary classification of whether the injection would be inside/outside the joint. It was calculated that there was 3 times the odds that the injection would be outside of the joint rather than inside the joint (OR=3.00; (1.29-7.00); p=0.011), based upon a typical joint size. This translates to a probability of 0.75 for injection outside of the joint without ultrasound (95% CI: (0.56-0.87)). The authors would like to note that despite the large odds of injection misplacement based upon this sample, due to the small sample size, there is considerable uncertainty around this estimate, leading to the wide confidence intervals.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrated that on average, a skilled investigator typically landmarks a space 8.6mm away from the nearest border of the AC joint and is more likely to be medial than lateral. Laterality is important, too, because the angle the joint makes is inferior and medial. Using the palpation-guided technique, a “lucky” angle is less likely to be achieved if the investigator is medial to the joint. It is worth noting that the pain experienced by the nearly 60% of patients who reported an adverse event during an AC joint injection cannot be differentiated between pain from piercing the skin or missing the joint. However, using POCUS to directly visualize the joint and the angle it makes, this landmarking error is eliminated. With a slow, deliberate approach under ultrasound guidance, the needle can be advanced between the acromion and clavicle in one steady movement. In addition, direct visualization of the injectate filling the joint space all but ensures a successful procedure, while minimizing patient discomfort.

Notwithstanding the fact that the width of a 25ga (0.52mm) needle can be greater than a normal AC joint in an elderly patient (<0.5mm), the chances of ‘blindly’ inserting a needle into a space as small as the AC joint without some manipulation is very unlikely. Each repositioning of the needle during a palpation-guided injection causes additional patient discomfort.

Within the constraints of our sample size, we noted that neither age, gender, nor BMI had a significant impact on the accuracy of palpation of the AC joint. It does, however, speak to the benefit of using ultrasound in all patients, not just those whose AC joints are suspected to be difficult to palpate (for example obese patients).

The challenge with the use of point-of-care ultrasounds in most joint injections is either the availability of the ultrasound machine or the time lost to set up. But in a clinic or emergency department where ultrasounds are used frequently, this should not be overly burdensome.

Because our study was designed to be non-invasive and limit the risk to our subjects, we did not inject anything into the AC joint. This meant we could not demonstrate that ultrasound-guided AC joint injections were superior to palpation-guided injections. Instead, we relied on the previous studies mentioned above, that used primarily cadaveric subjects, and recorded successful ultrasound-guided injection rates of 90-100%. It should also be noted that some studies have demonstrated only minor difference in pain relief when the injection was intra-articular compared to periarticular.14

We assumed that the investigator would insert their needle in the vertical axis through their pen mark. We could not readily account for any angle they might introduce into their approach to access the joint space. This meant that even if they were off by several millimeters, they could achieve the optimal angle necessary to pass between the anteromedial acromion and distal clavicle. We felt this limitation was mitigated by the fact that the actual angle the joint makes is impossible to know by palpation of the joint alone.

We also recognized that Primary Care Sports Medicine Fellows are still early in their careers and have not palpated and injected the number of shoulders that an experienced Orthopedic surgeon has. However, as one study showed, success rates of palpation-guided AC joint injections were nearly identical between Orthopedic specialists, non-specialists, and students.15 Additionally, this procedure can and should be easily performed in the Primary Care Clinic or Emergency Room setting. We should assume that providers in these environments do not have the experience in AC joint injections that the Orthopedic Surgeon does, nor even the Primary Care Sports Medicine Fellow. Nonetheless, future studies on the accuracy of palpation-guided AC joint injections might include the accuracy of providers of different skill levels, including residents and faculty from different specialties.

Future studies might also compare pain scores between palpation-guided and ultrasound-guided AC joint injection to assess patient satisfaction as well as accuracy. Though obtaining the number of subjects necessary to make this study effective might prove difficult.

Finally, we recognize that by not applying a formal random sampling process, it is conceivable that some bias may have entered into participant selection. Nonetheless, knowledge of the subjects’ AC joints prior to selection was not possible and further mitigated the risk of bias. A future study might apply a truly random selection process and expand the study size to achieve greater statistical power and generalizability.

CONCLUSION

Several recent studies have demonstrated that ultrasound-guided AC joint injections achieve greater rates of success than palpation-guided injections. Our study supports these findings and further emphasizes the inaccuracy of the palpation-guided technique. Indeed, the odds ratio of inserting a needle into the AC joint on the first attempt was 3. Whenever practical, providers should utilize ultrasound to guide their AC joint injections. This will not only ensure greater rates of success, but also minimize patient discomfort.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) patients who agreed to participate in our study. They also wish to thank the UMMC Simulation Center for the use of its resources in preparing the study design.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflict of interests.