Introduction

Venous sinus thrombosis and epidural abscesses are rare, feared intracranial complications of acute otitis media (AOM) that pose significant risks for the pediatric population.1 The most common complication is acute mastoiditis (AM), although the prevalence has decreased during the antibiotic era to approximately 0.24%.2 In rare cases, untreated AOM and subsequent mastoiditis can disseminate to the central nervous system and associated structures.

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) is seen as a potential complication of prothrombotic states such as pregnancy and malignancy, systemic inflammatory conditions, and infections including AOM and AM. CVST has an estimated incidence 0.67 per 100,000 cases of AOM and 1.6 per 100,000 cases of AM but seen in up to 2.7% of mastoiditis cases in certain studies.1,3 CVST is associated with serious complications, including motor deficits, vision loss, developmental delay, and death in 9-29% of cases.4 Epidural abscesses constitute one of the most common intracranial complications of middle ear infections. They were found in up to 6% of AM cases per Rosen et al. Patients with epidural abscesses are often initially asymptomatic , making this condition challenging to diagnose.5

Treatment of these complications is often difficult due to the acceleration of symptoms and the case variability. In addition, there is controversy surrounding particular interventions such as anticoagulation therapy, myringotomy with or without mastoidectomy, and internal jugular vein (IJV) ligation.6 This report presents a case of AOM complicated by CVST and an epidural abscess.

Case Presentation

A 12-year-old girl with history of juvenile idiopathic arthritis, MRSA cellulitis and osteomyelitis, and rheumatic fever on chronic penicillin prophylaxis presented to the emergency department with progressive symptoms of otorrhea, right face and neck pain, and decreased hearing concerning for mastoiditis. Seven days prior, the patient was treated with a dose of intramuscular ceftriaxone and a seven-day course of cefdinir at an outside hospital for ear pain and suspected AOM. Despite antibiotic adherence, her symptoms progressed, and she presented to another outside provider who administered additional ceftriaxone and changed her oral antibiotic to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, given her susceptibility to MRSA. Ten days following her initial symptoms, she presented to the ED reporting right-sided hearing loss, otorrhea, pre-syncope, decreased appetite and fatigue.

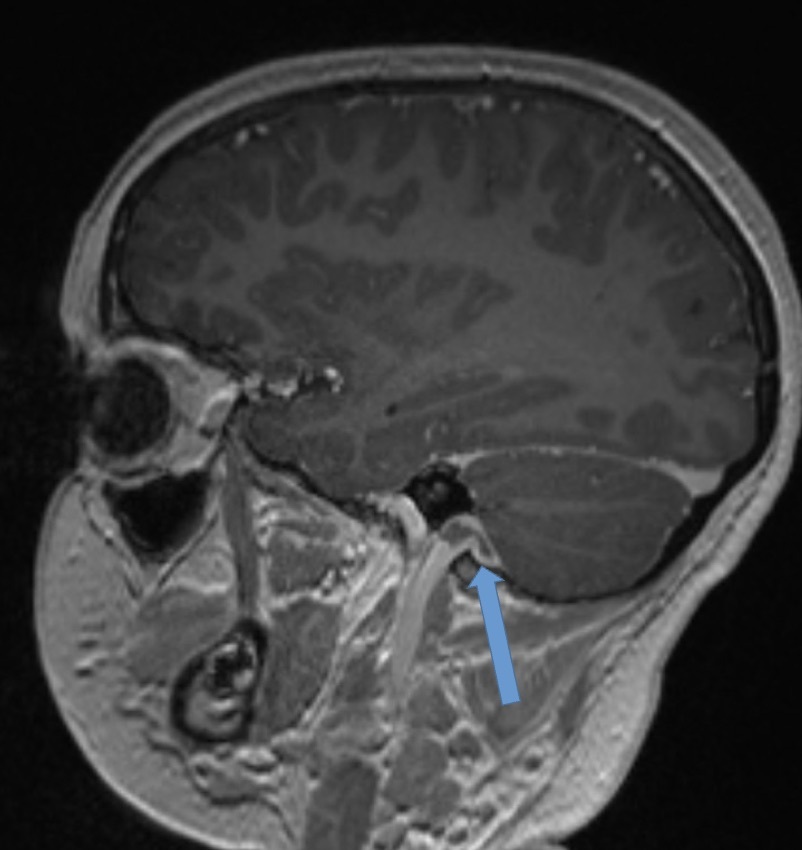

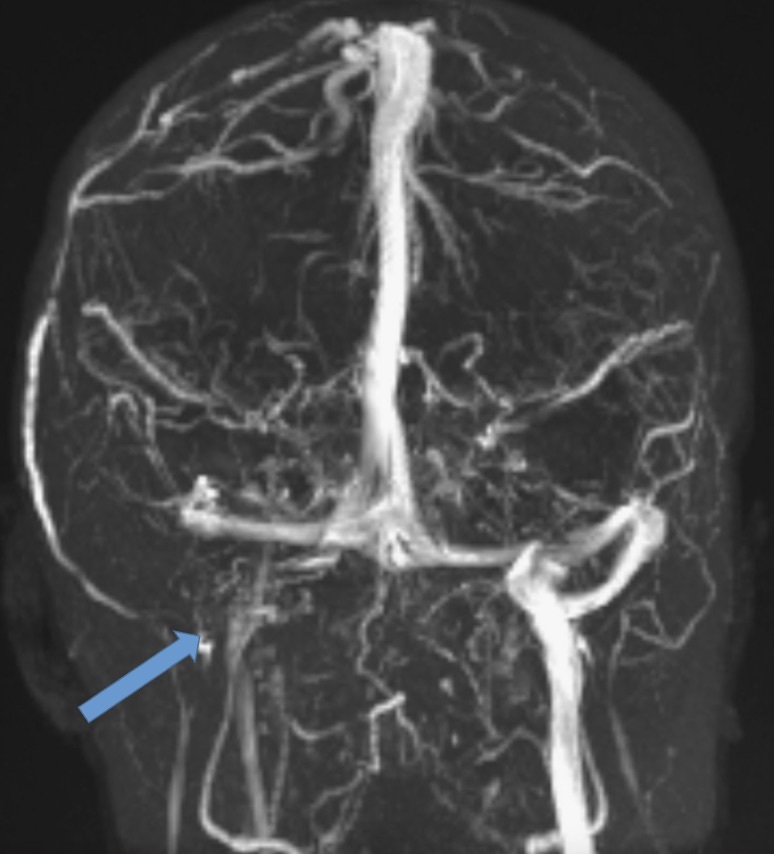

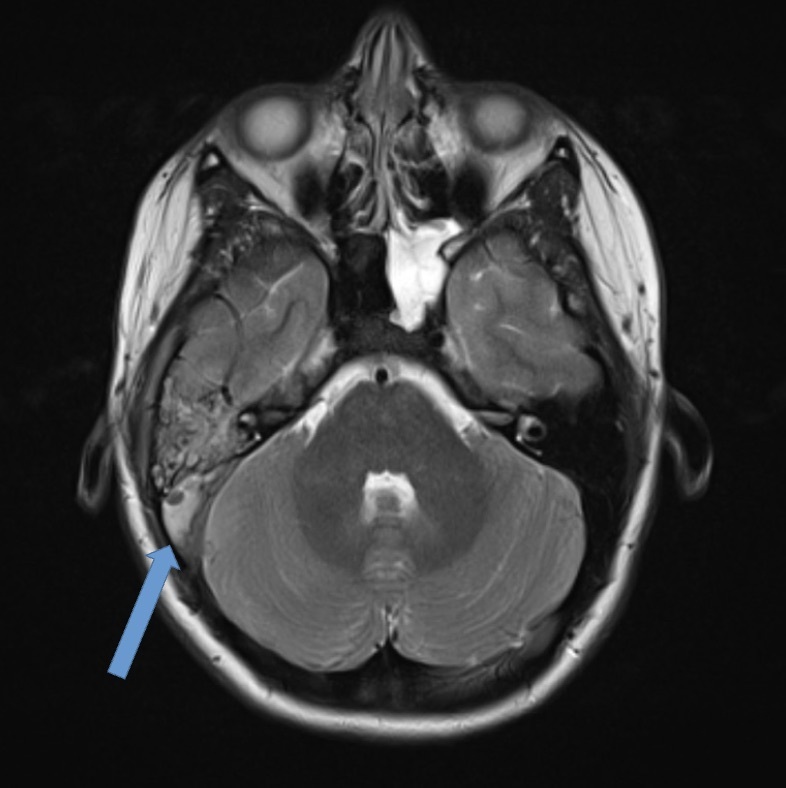

On presentation, she was afebrile and mildly tachycardic. Physical exam revealed a bulging right tympanic membrane with a purulent effusion, tenderness anterior to the sternocleidomastoid, and cheek swelling. There was no notable mastoid tenderness or neurologic deficits. Complete blood count (CBC), complete metabolic panel (CMP), C-Reactive protein (CRP), and procalcitonin were within normal limits. Blood cultures were negative. Computed tomography (CT) neck revealed right mastoiditis with dehiscence along the posterior wall of the right mastoid air cells (Figure 1) and concern for IJV thrombus. Hematology and otolaryngology were subsequently consulted. The patient was started on enoxaparin, along with meningitic-dosed vancomycin, metronidazole, and cefepime. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance venogram (MRV) of the internal auditory canals were obtained which demonstrated ipsilateral otomastoiditis with thrombosis of the right distal transverse and sigmoid sinuses (Figure 2) and proximal right IJV (Figure 3) as well as concern for cerebellar cerebritis with presence of an epidural abscess (Figure 4). The patient underwent a myringotomy with tube placement and mastoidectomy with drainage. Intraoperative findings were significant for middle ear purulence, granulation tissue in the mastoid cavity and a small sigmoid sinus defect where purulent drainage was identified. Intraoperative cultures were positive for Streptococcus pneumoniae resistant to clindamycin, erythromycin, penicillin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Ophthalmology was consulted to evaluate for papilledema, where grade one optic disc edema was noted. After post-operative recovery, she was discharged with a PICC line for 42 days of intravenous vancomycin and ceftriaxone, oral metronidazole, along with 6 months of enoxaparin for anticoagulation.

Two weeks following discharge, an ophthalmology follow-up showed progressively decreased visual acuity. Exam was positive for grade three optic disc edema along with a right abducens nerve palsy. She was readmitted, where repeat imaging showed decreased clot burden from prior exams and improved cerebritis. Patient underwent therapeutic lumbar puncture with an opening pressure of 30 cm H2O and was discharged. She was later readmitted for persistent bilateral papilledema requiring optic nerve sheath fenestration via ophthalmology. Ultimately, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt was placed for continuously elevated opening pressure. Since discharge, she continues routine follow-up with ophthalmology, neurosurgery, and otolaryngology services. Despite mild vision loss, she sustained no long-term neurological deficits.

Discussion

CSVT and epidural abscesses are rapidly progressing sequelae of delayed or insufficient treatment of AOM, especially in the presence of subsequent mastoiditis. In this patient, initial antibiotic therapy was insufficient and resulted in life-threatening conditions leading to permanent visual deficits despite timely diagnosis and intervention. Insufficient treatment for AOM is multifactorial, including low adherence, insufficient dosage, bacterial resistance, and local anatomical variants that decrease perfusion to the infected areas.5,7 Mastoiditis often takes 10-14 days to develop after AOM onset, but may present more rapidly, particularly in patients with known immunodeficiencies.5 Clinicians should be wary of patients with AOM who display increased susceptibility to infection. This patient’s past medical history of serious staphylococcal and streptococcal infections raise suspicion for underlying immunodeficiency, possibly due to her untreated rheumatologic disease. Cases of CVST have been linked to chronic diseases even in the absence of concurrent infectious processes.8 CVST patients should also be evaluated for underlying hypercoagulable states that predispose patients to thrombosis.9 Additionally, since epidural abscesses can be difficult to detect, imaging should be performed in patients who develop mastoiditis despite antimicrobial therapy, even without neurological symptoms.5

Treatments for severe AOM complications, such as CVST and epidural abscess, vary case-by-case but usually involve IV antibiotics, myringotomy with tube placement, mastoidectomy, and abscess drainage.6 Anticoagulation use is debated in treating CVST due to the risk of hemorrhagic events, thrombocytopenia, and skin necrosis. In the absence of hemorrhage on imaging, current guidelines by the British Committee for Standards in Haemotology and the American College of Chest Physicians recommend low molecular weight heparin for CVST due to its more favorable side effect profile.3,6 Mastoidectomy as an intervention has shown positive outcomes of CVST; however, some cases report similar positive results without mastoidectomy, thus the need for additional studies.6,10 In this case, the presence of an epidural abscess necessitated mastoidectomy with drainage.

Conclusion

AOM, while common in the pediatric population, can be associated with rare but serious complications given the ear’s proximity to important vascular and neurologic structures. Prompt evaluation and treatment of these patients, particularly in those with suspected immunologic deficits, is critical in reducing the incidence of these various complications.

Informed Consent

Informed consent for this case report was obtained from this patient’s mother.