Background

Gender is a societal construct associated with the sex one is assigned at birth.1 The term “transgender”, sometimes abbreviated as trans, is used to describe individuals whose gender identity and sex assigned at birth do not correspond to traditional expectations.2 The trans population includes but is not limited to people who identify as trans women, trans men, or those whose gender identity is outside the girl/woman and boy/man gender binary structure.1 Medical interventions are common among trans individuals, such as gender-affirming hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgeries to attain physical characteristics that better align with their gender identity.3 These interventions create various healthcare needs, including societal, medical, and surgical procedures requiring diverse and unique healthcare services to receive appropriate care and achieve a good quality of life.4

However, limited expertise, lack of knowledge on culturally competent trans care, and implicit bias of providers are associated with health disparities in trans patients. Consequently, trans individuals have elevated substance use disorders, sexually transmitted infections, suicidality, and poorer mental health compared to their heterosexual and non-heterosexual cisgender counterparts.5,6 Health disparities among trans patients are linked to stigma, inequity, and inadequate clinical training of providers to address the specific health needs of this community, suggesting that long-standing discrimination and lack of preparedness among healthcare professionals hinder effective diagnosis and treatment.7 Poor healthcare practices negatively influence trans healthcare experiences, their perceptions of healthcare, and their future interactions/encounters with the healthcare system.

Concequently, there is a critical necessity to prepare and educate medical trainees on trans issues/concerns in healthcare to provide culturally competent and sensitive care. Training and education on trans health needs can help trainees become more aware, sensitive, and inclusive in providing care to trans patients. Proper care for trans and gender-diverse people requires a multidisciplinary approach and training on recognizing and addressing healthcare needs and issues to provide equitable care for this diverse population.8 Many healthcare professionals require developing new communication skills, knowledge, awareness, attitudes, and receptivity for the trans population.9

Recently, graduate medical education (GME) has begun developing curricula to enhance education regarding the health needs of trans patients and reduce the stigma these individuals face when accessing care.10 The Academic Medical Center is Mississippi’s only academic medical school and follows all educational requirements determined by the American Council on GME. Like most medical schools, this academic medical center does not currently have any formal training specific to trans care in the GME curriculum. This issue may be due to a lack of confidence in teaching the curriculum or unfamiliarity with the intricacies of trans healthcare. Implementing training courses throughout GME programs’ curriculum could help alleviate health disparities and shed light on unconscious bias. The first steps to incorporating specific trans-educational training include determining interest in additional training, perceived knowledge level and deficits in knowledge, and anticipated benefits of increased education on this patient population. Therefore, this study aims to identify GME trainees’ comfort and competency regarding trans healthcare to develop a trans healthcare curriculum for trainees enrolled in GME at an academic medical center. Thus, this study will identify some common perspectives and knowledge gaps among trainees.

Methods

Participants

This research study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB 2021-1037). For this cross-sectional study, a 16-question quantitative survey was created for GME trainees at our medical center. The survey was administered and recorded by REDcap® (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN), an anonymous and secure survey distribution tool. The REDcap® survey was sent by email to all GME trainees (n=647) enrolled at our medical center during the approved survey distribution period. Surveys were dispersed and collected from January to March of 2022. Reminder emails were sent every 2 weeks during the approved study collection period. Email addresses were obtained through the GME office at our medical center.

Data Collection

The survey invited all trainees to participate in a voluntary, anonymous survey regarding self-perceived competency in trans healthcare and interest in trans healthcare training. Trainees self-reported personal awareness of inclusive language and resource availability and perceived level of involvement in trans healthcare. These questions were administered in the format of 6 dichotomous (yes/no) questions and 8 Likert scale (completely, for the most part, neutral, somewhat, not at all) questions. The survey also assessed post-graduate year (PGY) in training and area of specialty. PGY was not separated based on trainee type (intern, resident, fellow).

We evaluated survey responses for association with specialty and years of post-graduate training. Due to variation in specialties represented in survey responses, specialties were combined into primary and non-primary care. Primary versus non-primary specialties were defined by the authors. The length of PGY training differs by area of specialty. In the specialties represented, the minimum training for all specialties is 1-3 years and the maximum is 1-7 years. Due to this variation, we evaluated responses in 4 PGY groups- PGY1, PGY2, PGY3, and PGY4+. A list of the 33 specialties by primary and non-primary care and PGY is represented in Supplemental Material 1.

Data Analysis

All surveys were used in the analysis. Since each question was independent, incomplete surveys were used in survey analysis. The difference in the number of responses per question is due to question skipping by some respondents. Missing survey responses were deemed random, and these surveys were still used to evaluate answered questions. Survey responses were extracted and recorded in an Excel® spreadsheet program. Descriptive responses of survey answers by trainees were recorded and graphically represented. PGY and specialty with answer selection were assessed by statistical analyses using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Fisher’s Exact Test was used to measure differences between categorical responses. This analysis was completed in collaboration with the Biostatistical Core. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant if P< 0.05.

Results

Response Rate and Specialties

A total of 126 responses were collected from an email survey sent to 674 trainees (19.5% response rate). Of the 126 total surveys included in this study, 33 specialties were recorded. Seventy-four of the trainees were non-primary care specialists (58.7%), and 52 trainees were primary care specialists (41.3%) (Table 1). The distribution of PGY trainees was 19.0% PGY 1 (n=24), 23.0% PGY 2 (n=29), 23.8% PGY 3 (n=30), and 34.2% PGY 4+ (n=43).

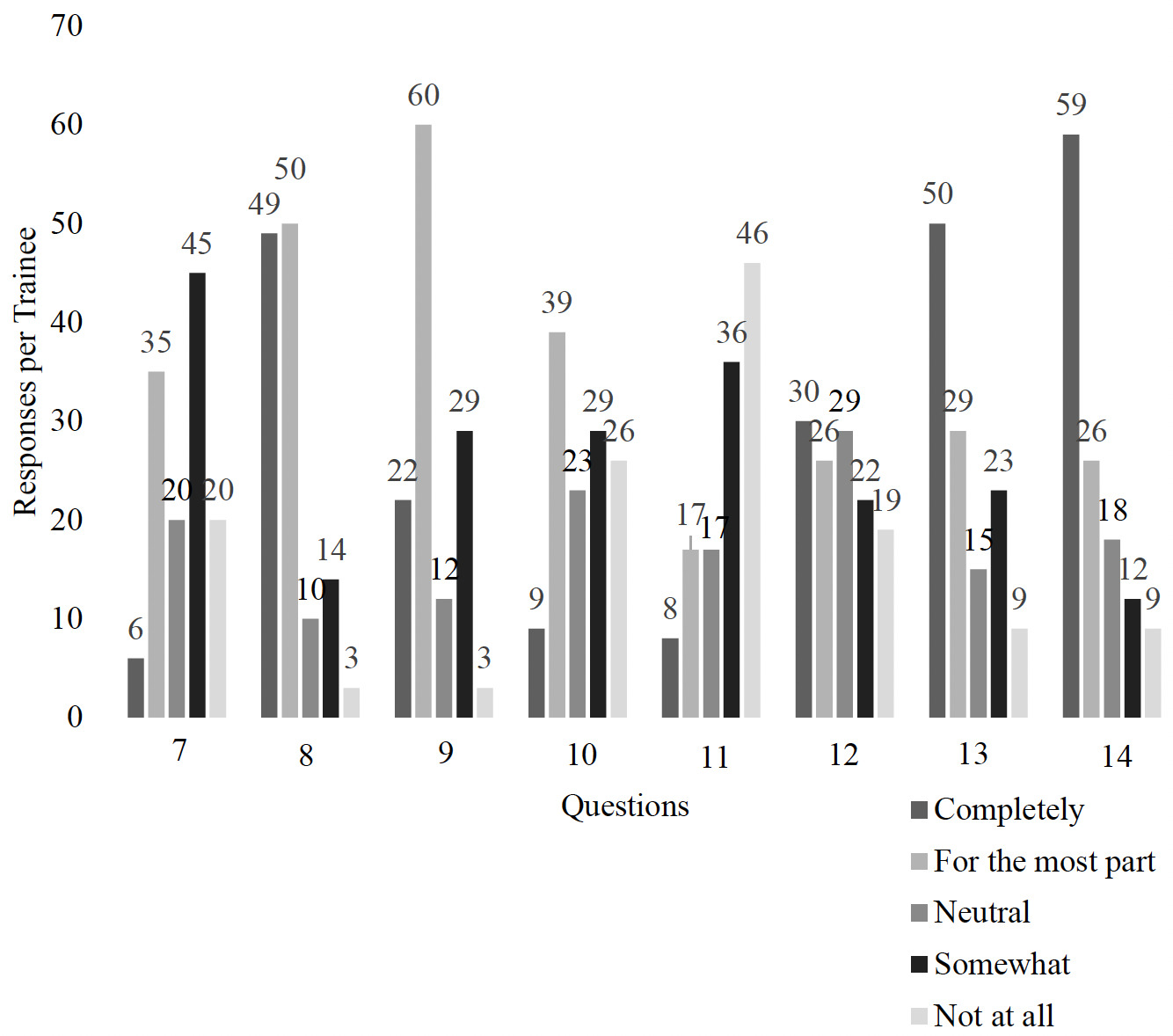

We evaluated the responses of all n=126 trainees. Total responses for dichotomous and Likert scale questions are listed in Table 2 and graphically represented in Figures 1 and 2. When trainees were asked about the importance of receiving training on healthcare issues specific to transgender patients, 92.8% (n=117) reported “yes.” The majority of trainees were not comfortable managing (61.1%; n=77) or helping patients receive (65.9%; n=83) gender-affirming healthcare. Fifty-five point six percent (n=70) of residents have asked patients for their preferred pronouns, and 91.3% (n=115) are aware of alternative pronouns.

Trainees were asked about their awareness, confidence, and interest in general transgender healthcare. When asked about confidence in the management of transgender patients’ health concerns, over half of the respondents (51.5%, n=65) felt either “not at all” (15.9%, n=20) or “somewhat” (35.7%, n=45) confident. Seventy-eight point five percent of respondents (n=99) identified knowing and being comfortable discerning the difference between gender identity and sexual orientation with 38.9% (n=49) marking “completely” and 39.7% (n=50) marking “for the most part comfortable.” Sixty-five point one percent (n=82) of trainees indicated feeling “completely” (17.5%, n=22) or “for the most part” (47.6%, n=60) aware of trans healthcare barriers, with just 2.4% (n=3) feeling “not at all” aware. However, only 7.1% of trainees (n= 9) were completely aware and comfortable in caring for trans patients. In response to familiarity with additional guidelines for transgender health, 66.1% (n=82) stated they felt “somewhat” (29.0%, n=36) or “not at all” familiar (37.1%, n=46) with the reference guidelines. Trainees’ opinion on their role in trans healthcare was evenly dispersed. However, when trainees were asked if they were interested in receiving further training about trans patient care, 62.7% (n=79) of GME respondents indicated “completely” (39.7%, n=50) interested or “for the most part” (23.0%, n=29) interested in receiving further training related to transgender healthcare. Forty-seven point six percent (n=59) “completely” and 21.0% (n=26) “for the most part” believed that they would benefit from further training in trans patient care.

Responses by PGY and Specialty

We evaluated if specialty or PGY influenced survey responses; a list of responses per question by specialty and PGY per question is shown in Supplemental Table 2. PGY did not influence survey responses to dichotomous or Likert scale questions. Analysis revealed that the area of specialty (non-primary vs. primary) among respondents influenced some areas of confidence and knowledge of trans care. Seventy point three percent (n=52) of non-primary and 90.4% of primary (n=47) care specialists reported that they were interested in learning more about healthcare issues specific to trans care, but, interestingly, 29.7% (n=22) of non-primary care specialists reported “no” (P<0.01). In regard to confidence in the management of health concerns of trans patients, non-primary care specialists were “for the most part” (36.5%; n= 27)

confident in their ability (P<0.01), whereas, 44.2 % (n=23) of primary care specialty were “not at all” confident in their ability to manage transgender health concerns (P<0.01). The majority of both non-primary and primary care trainees understood and were comfortable with the difference between gender identity and sexual orientation, with 85.2% (n=63) non-primary and 69.2% (n=36) primary specialty trainees reporting “completely” or “for the most part” (P=0.11). Both non-primary (54.1%; n= 40) and primary (38.7%; n= 20) care specialists were “for the most part” aware of barriers to healthcare experienced by trans patients (P=0.50). Trainees from non-primary specialties were more aware and comfortable caring for the health issues of trans patients, with 37.8% (n=28) reporting that they were “for the most part” comfortable (P=0.03). Nonetheless, familiarity regarding where or how to seek guidance for trans healthcare was similar among specialties, with 32.9% (n=24) non-primary care and 43.1% (n=22) primary care trainees selecting that they were “not at all” familiar, and 27.4% (n=20) non-primary and 31.4% (n=16) primary trainees reporting that they were “somewhat” familiar (P=0.19). Although primary care trainees were less likely to feel confident and comfortable in trans healthcare, primary care specialists were more aware of their role in promoting transgender care, with only 3.9% (n=2) of primary care trainees recording that physicians in their role are “not at all” important in promoting trans care (P<0.01). Responses regarding the interest and perceived benefit of further training in caring for trans patients were similar among specialties.

Discussion

This study indicates that Mississippi GME trainees recognize existing healthcare barriers in the treatment of trans patients and are not confident in their ability to provide care specific to the unique needs of trans patients. Additionally, trainees do not fully understand their current role in advocating for their trans patients’ needs, and trainees are not fully confident in how to find adequate resources to combat healthcare barriers. Although the confidence in trans care is bleak among Mississippi trainees, they recognize that trans healthcare is complex and warrants implementation in the GME curriculum.

The year of training did not influence confidence among trainees, which supports the lack of trans-healthcare training in the GME curriculum. Interestingly, non-primary care trainees reported feeling more comfortable with healthcare issues regarding and surrounding trans care than primary care fields. However, primary care physicians believe that their role as physicians plays an important role in trans care. These data indicate that more emphasis is being placed on trans care within non-primary care specialties outside of the GME curriculum as compared to primary care specialties. Perhaps primary care providers feel that their specialties are more relevant to the healthcare of trans patients than non-primary care specialties, increasing their self-perceived role in trans care. Trans patients may receive care more frequently in primary care specialties either as a stand-alone visit or as an initial visit prior to a referral to another specialty, increasing the facetime with primary care specialists. However, primary care specialists are not confident in their abilities to manage and provide appropriate healthcare to trans patients, indicating that trans healthcare training is warranted, especially for physicians who routinely see trans patients. Additionally, the elevated confidence in trans care among non-primary care specialists further supports the notion that trans care should be multi-disciplinary and incorporated into the curriculum of all specialties.

A meta-regression analysis of the United States population from 2006-2016 indicated significant annual increases in trans adults.11 Currently, trans-Americans make up about 0.5% of the population, which is approximately 1.6 million Americans.12 We utilized the patient cohort explorer (PCE) from our medical center, an online de-identified database of patients compiled from hospital records at hospitals and clinics, to estimate the number of trans patients treated at our medical center over the last decade. We identified 68 trans-patient encounters from 2013-2022. Only 10 recorded encounters occurred from 2013-2017; however, 48 encounters were recorded from 2018-2022, an increase of 380% over 5 years.13 It is important to note that the PCE does not always capture trans patients cared for at our medical center, but over 900,000+ patients are available in the dataset, which allows for a vast representation of the patient makeup at our medical center. Although the total number of reported trans patients is low at our medical center, these data indicate that patients identifying as trans are increasing in our academic medical center and likely indicate an increase in trans patients throughout the state of Mississippi and nationwide; thus, our study indicates that it is imperative to increase trans training and education efforts locally and nationally among GME trainees.

With the lack of confidence in trans healthcare and the growing number of trans patients visiting the hospital or clinic, it is clear that there are gaps in the GME curriculum. Studies show that undergraduate and graduate medical education with an LGBTQIA+ curriculum built in improved knowledge and confidence in LGBTQIA+ healthcare.14,15 A longitudinal study on implementing trans healthcare training in the curriculum reports improvement in undergraduate student knowledge of gender-affirming care and the ability to address hospital and clinic barriers.16 A pilot intervention in residents indicates that a 4-month LGBTQIA+ curriculum increased residents’ confidence to provide care.17 These studies suggest that trans healthcare education can improve the knowledge and confidence of physicians, which will impact the overall health and well-being of the growing trans population. As the stigma surrounding trans confirmation surgery decreases in the United States, deficiencies in trans healthcare will continue to become more apparent. Therefore, it is imperative to provide cultural competency and sensitivity training to GME trainees to ensure empathetic and competent care for trans individuals to minimize unintentional harm and change systemic barriers that contribute to trans health disparities.

A major limitation of this study was the low response rate and the limited dispersion of trainees in various specialties. This low response rate may influence potential bias in that only trainees interested in trans health care responded to the survey. Given the overall positive responses and given the fact that our medical center is the state’s only academic medical center, there seems to be sufficient evidence gathered in this study to suggest an interest and benefit in additional educational training related specifically to trans care among GME trainees.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

_responses_per_trainee.png)

_responses_per_trainee.png)