Introduction

Acute liver failure (ALF) is characterized by sudden onset synthetic dysfunction of the liver manifested by hepatic encephalopathy and coagulopathy without preexisting liver disease.1 The etiology of ALF helps to guide management and to assess prognosis.2 A rare cause of ALF is malignant infiltration of the liver in which case it is more commonly associated with hematologic malignancies such as lymphomas and leukemias but can also be a result of solid tumor malignancies. The Acute Liver Failure Study Group (ALFSG) reported that only 1.4% cases of ALF between 1998 and 2012 in the United States were due to malignant infiltration. Amongst these, there were no documented cases of prostate cancer.3 Here we present a rare case of ALF in a patient with diffuse hepatic infiltration by metastatic prostate cancer.

Case Report

A 66-year-old Caucasian male with a past medical history of castration-resistant prostate cancer with bone metastases presented with abdominal bloating, early satiety, constipation, and occasional vomiting for 1 week. This was associated with 12-lb weight gain despite decreased food intake. Family also reported increased drowsiness. He denied prior history of ascites, hematemesis, melena, jaundice, or encephalopathy. He did not have a past medical history of liver disease but stated that his oncologist had told him about elevated liver function tests, 10 days ago. He denied a history of alcohol, tobacco, illicit drug, herbal supplement, or over-the-counter drug use including acetaminophen containing medications. He was diagnosed with localized prostate cancer 3 years ago at another facility. Based on review of accessible records, he was treated with leuprolide and bicalutamide for chemical castration in addition to localized radiation. He was in remission until 5 months prior, when his prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was found to be elevated once again, and he was found to have bony metastases. Since then, he was treated with abiraterone and prednisone. After this, he also underwent treatment with docetaxel. He had completed docetaxel for 4 months, 6 weeks prior to presentation. Despite treatment, PSA levels continued to rise, and osseous disease had progressed on computed tomography scan (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans 2 weeks prior. He was scheduled to start lutetium (177Lu) vipivotide tetraxetan in the coming weeks.

On admission, vital signs were unremarkable. Physical exam was positive for mild drowsiness, jaundice, asterixis, ascites, and lower extremity pitting edema. Initial labs were significant for platelet count 142 TH/cmm, sodium 130 mmol/L, creatinine 1.45 mg/dL (elevated from 0.8mg/dL, roughly 4 weeks prior), aspartate aminotransferase 200 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 86 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 326 U/L, total bilirubin 2.08 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 1.46 mg/dL, International Normalized Ratio (INR) 2.01, prothrombin time 23.2 sec, PSA 1,420 ng/dL and ammonia 83 µmol/L. Other labs such as phosphorous levels (at presentation and 48 hours of admission were >3.0mg/dL), viral hepatitis panel, and thyroid-stimulating hormone were unremarkable. CT abdomen/pelvis with intravenous contrast demonstrated 18 cm hepatomegaly, hepatic steatosis, and ascites but no suspicious hepatic lesions, infiltration, or biliary dilatation. Hepatic dopplers revealed patency and normal direction of flow of the main hepatic artery and vein; however, reversal of flow in the main portal vein along with splenomegaly was visualized. There was concern for ALF given elevated INR, hepatic encephalopathy (grade II), abnormal hepatic function panel, and no prior history of liver disease.

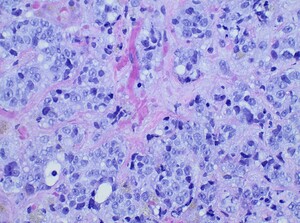

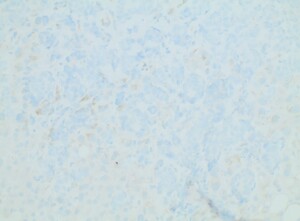

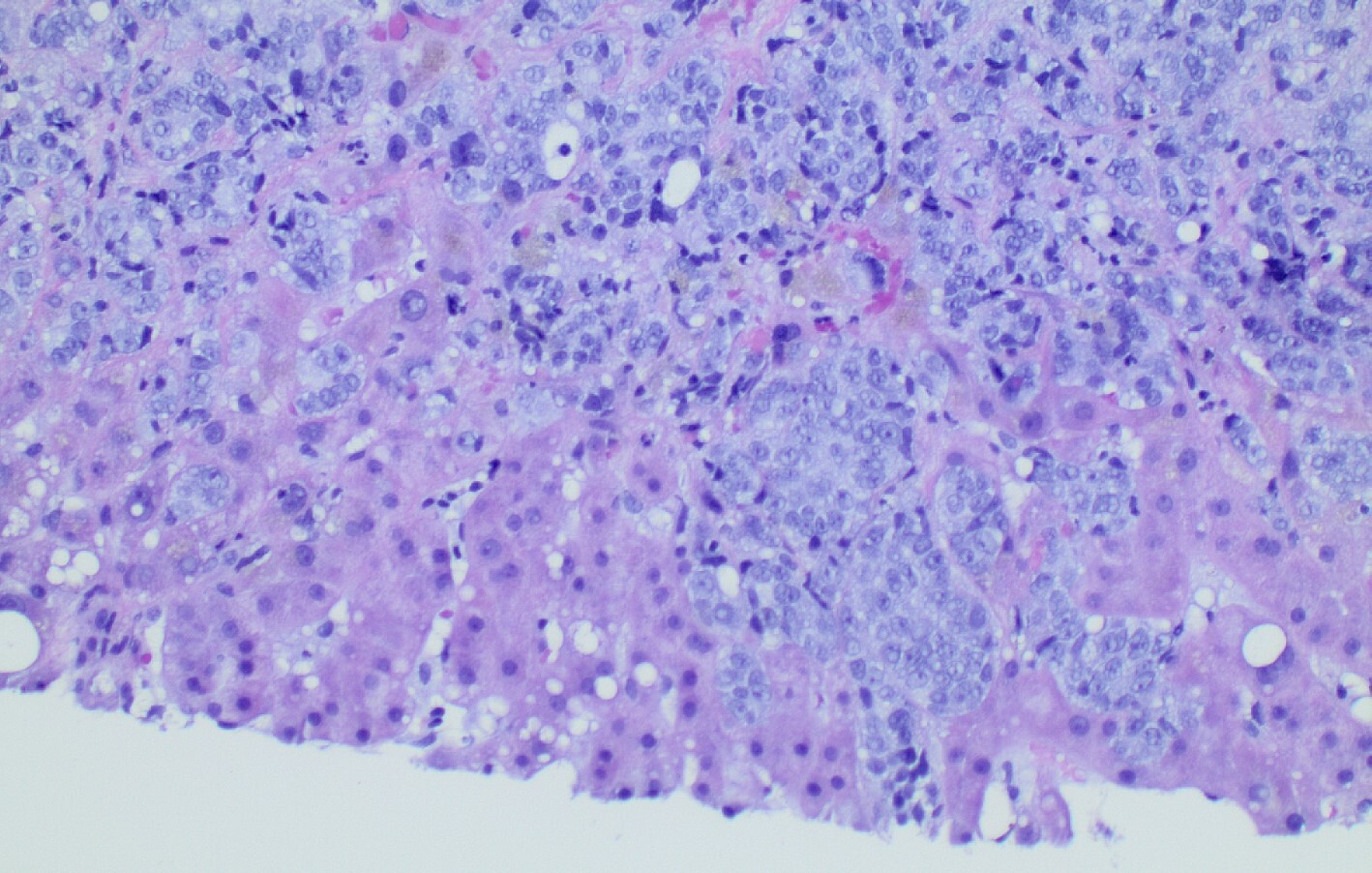

Diagnostic paracentesis was performed and revealed an ascitic protein of 0.9 g/dL, and serum-ascites albumin gradient was calculated to be 2.8. Given his prior history of docetaxel use, the decision was made to proceed with a trans-jugular non-targeted liver biopsy to rule out medication induced hepatic veno-occlusive disease. Hepatic venous pressure gradient was found to be elevated at 32 mmHg. The liver biopsy revealed infiltrative adenocarcinoma from known primary prostate cancer with immunohistochemical staining significant for positive NKX 3-1 and negative CK7 and CK20 (Figures 1-5). The patient was diagnosed with ALF secondary to infiltrative prostate cancer and did not meet transplant criteria due to malignancy. Considering the information provided via the liver biopsy, it was determined the lutetium (177Lu) vipivotide tetraxetan therapy would be ineffective. After extensive conversation, the patient and his family opted for home hospice to spend valuable time with loved ones. The patient was discharged after a total hospital stay of 6 days. He expired less than 2 weeks after discharge.

Discussion

ALF is a rare disease that is characterized by the presence of coagulopathy (INR>1.5), hepatic encephalopathy, and onset of liver dysfunction within 26 weeks without preexisting liver disease.4 The management and prognosis of ALF can vary based on the etiology. A recent national cohort study highlighted an association between etiology and waitlist mortality.2 This highlighted association demonstrates the importance of determining the cause of ALF early in the course of hospitalization.

The ALFSG determined that only 1.4% of cases of ALF between 1998 and 2012 in the United States were due to malignant infiltration. Amongst these, there were no documented cases of prostate cancer metastasis.3 Although it is common for prostate cancer to metastasize to the liver, being the third most frequent site of spread after bone and lung, severe hepatic dysfunction from metastatic infiltration is rare.5 Furthermore, data suggests an incidence of 25% of clinically silent metastases to the liver which were found at the time of autopsy.6 This finding raises the question of if malignant infiltration could be a potential cause of ALF of unknown etiology. As in our case, malignant infiltration was identified neither on CT nor PET scans 2 weeks prior to presentation.

Amongst the differentials were drug-induced liver injury and hepatic veno-occlusive disease, given that the cause of ALF could not be determined on serum tests and imaging alone. The liver biopsy played a pivotal role in determining the diagnosis and, in essence, the management plan. Our case also underscores the complexity of diagnosing acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) in the setting of malignancy and prior chemotherapy, as the patient’s underlying liver function status was unclear. Pre-existing liver pathology exacerbated by the diffuse metastatic disease and chemotherapeutic effects may have contributed to his rapid decompensation; however, there were no alternative causes identified by histopathology. Thus, clinicians must have a high index of suspicion when approaching a case of ALF or possibly ACLF of indeterminate etiology. Early liver biopsy in indeterminate cases can help guide future care: avoidance of needless treatments as well as wastage of patient’s time and finances, and enabling more appropriate end-of-life care favoring quality time spent with loved ones.

It is also notable that our patient did not meet King’s College Criteria (KCC) for non-acetaminophen ALF.7 KCC was introduced in 1989 and is a culmination of prognostic indicators used to determine transplant needs. KCC is considered highly specific but not sensitive, and, therefore, new advancements in prognostic models, management, and non-transplant therapies have surfaced. Options for inpatient care expanded with the use of therapeutic plasma exchange, renal replacement therapies, non-invasive intracranial pressure monitoring, and identifying and correcting coagulopathies in addition to liver transplantation.8 Similarly, predicted transplant-free survival at 21 days using the ALFSG prognostic tool was 77%; however, the patient expired within this period. This information highlights the need for reassessing the validity of existing diagnostic and prognostic tools for indeterminate causes of ALF. Some data suggests that malignant infiltration is an independent marker of poor prognosis for 30-day mortality.9 Furthermore, our patient had normal phosphate levels which has also been shown to have an association with worse prognosis in some studies.10,11 Further studies on ALF stratified by etiology would be useful to better characterize diagnosis, presentations, management, and outcomes for this patient population.

This case report was presented at the American College of Gastroenterology Annual Meeting, 2023.