Images in Mississippi Medicine

THE RISE OF THE FEMALE PHYSICIAN IN MISSISSIPPI: A REVIEW OF THE LIVES OF PIONEER PHYSICIANS MAY FARINHOLT JONES, MD (1866-1940), SARA ALLEN CASTLE, MD (1861-1938), ROSA DOUGLASS WISS, MD (1868-1931) —

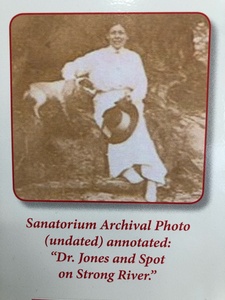

When I recently visited the Sanatorium Museum, located on the grounds of the historic Boswell Regional Center near Magee (a future topic for this column), I discovered a photograph of Dr. May Farinholt Jones and her dog Spot sitting adjacent to nearby Strong River. The image dates from the 1920s, her period of service at the tuberculosis institution as the right hand of Dr. Henry Boswell, founder of the sanatorium. The faded photograph from almost a century ago reminded me of the critical yet understated role this female medical pioneer played not only in public health service but also in the advancement of women in the practice of medicine in our state and country. Along with Dr. Jones are two other women, Dr. Rosa Douglass Wiss and Dr. Sara Allen Castle, who made groundbreaking strides in the practice of medicine by women in Mississippi.1

The Mississippi State Medical Association (MSMA) was progressive and even ahead of its peers in integrating women, at least white women, into its ranks and leadership. It was fifty-two years after Elizabeth Blackwell, the first female in the United States to receive a medical degree, that our MSMA admitted to its ranks in 1901 its first female members, May Farinholt Jones, MD (1866-1940) and Rosa Douglass Wiss, MD (often misspelled Weiss; 1868-1931). Jones is given credit for being the first female member of the MSMA, and Wiss appears to be the state’s first female physician to pass the state medical board and receive a license. Jones’s appearance in the association’s transactions coincides with the presence of Wiss, and the two would soon be joined by Sara Allen Castle, MD (1861-1938) of Meridian. A review of the early MSMA records and newspaper records reveals the three as the most prominent female physicians in the state in the first decades of the twentieth century. Who were these pioneer female physicians of Mississippi?

Born and reared in New Kent County, Virginia, Dr. Jones was one of several children of Benjamin and Lelia May Farinholt. (Benjamin was a decorated Confederate Colonel who had served in Pickett’s command.2) While her full name was Anna May Farinholt, she always went by “May.” She married Vernon F. Jones, who died early in their marriage, and one obituary notes that she had a son named Malcolm Jones, who would live with his mother in Laurel for a period. Her husband’s death appears to have been the impetus for her to attend the Woman’s Medical College of Baltimore, one of the first female medical institutions in the country, where she graduated with an MD in 1897. Her post-graduate education was impressive, training with legendary Sir William Osler at Johns Hopkins University.3 After her work in Baltimore with Osler, she moved to Mississippi in 1901 to begin her career as resident physician at the Mississippi Industrial Institute and College, the state’s premiere college for white females, which had been established in Columbus in 1884. (This institution is now Mississippi University for Women.) She would not be the only pioneer female physician to be welcomed into the state via a job offer from a female college to care for female students. In preparing for this appointment, Jones became one of the first woman to take and pass the state medical board examination in 1901. Dr. Elizabeth Bass (1876-1956), a native of Marion County, Mississippi, who obtained her MD in 1904 from the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania and later became the first female faculty member at Tulane Medical School and who interacted with Jones, wrote in 1952, “Dr. May Farinholt Jones studied medicine after the death of her husband and graduated from the Woman’s Medical College of Baltimore. She was the first woman physician at the Mississippi State College for Women (formerly Industrial Institute and College), the first woman to take the Mississippi State Board medical examination, and the first woman physician admitted to the Mississippi State Medical Society.”4,5 Despite her deserved reputation as one of the first and foremost historians of the medical history of women in the United States, Bass was wrong on one point: Dr. Jones was not the first licensed female physician in the state. However, she is correct on the other points. Jones did specialize in student health medicine, becoming the physician for the all-female Mississippi State College for Women (now MUW) in Columbus and later Professor of Hygiene and Sanitation and resident physician for the Mississippi Normal College (now USM) at Hattiesburg in 1912. Jones’s hometown Virginia newspaper, The West Point News, reported in October 1907, “Dr. May Farinholt Jones, after returning from an extended and delightful travel through England, Scotland, and France came by West Point to spend a few days with her parents, Col. and Mrs. B. L. Farinholt, and has returned to Mississippi, where for the past several years she has been resident physician to the largest Female College in the South at Columbus, Mississippi. Dr. Jones has recently accepted the position as Dean and Resident Physician of the Woman’s Department of the University of Mississippi, which is a flourishing co-educational institution.”6 This 1907 article indicates she may have also served as physician at Ole Miss prior to her arrival in Hattiesburg.

Drs. Jones and Wiss appear to have joined the MSMA close to the same time, 1901. The state press recorded during the May 1901 annual MSMA session that the gathering “was taken up in reading and discussing various questions of interest to the fraternity.” Despite calling the MSMA by the masculine “fraternity,” suggesting the rarity of a female member, the press noted with excitement, “The attendance has considerably increased since yesterday, about 100 delegates being now enrolled, including two lady members of the profession, Dr. May F. Jones, of the Industrial Institute and College, and Dr. Rosa Weiss <sic>, of Meridian.” The Clarion-Ledger added in their coverage of the session, “Both of these ladies hold high rank in the profession and are among the very few women doctors in Mississippi.”7,8 These articles in 1901 assert Jones and Wiss as the first female members of the MSMA, joining as early as May 1901.

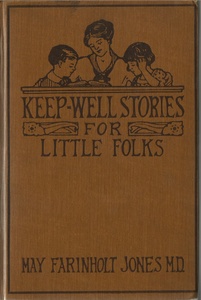

Both women appear to have been embraced by the association at this meeting, and Dr. Jones would become a regular participant at later meetings, being asked to address members at annual session as well as to take on leadership roles. She delivered scientific lectures on subjects from typhoid fever to influenza. No doubt she was a gifted mind and an excellent physician. During her period of medical work, she was recognized as the leading female physician in the state. Our MSMA would become one of the first state associations in the country to place one of their female members in a high office when in 1903, Jones was elected as second Vice President of the association, the third highest office in the association hierarchy. Strangely, after assuming this high office, she would not hold any other major offices, although she would consistently attend and frequently address the annual sessions with medical talks. Dr. Jones, while serving at Mississippi Normal College, explored with her teaching students how to present effectively hygienic facts to children. The result was the popular children’s textbook Keep-Well Stories for Little Folks, first published in 1916 and republished in 1925. This small hardback volume, which includes imaginative stories and poems, was used in the primary schools of several states.

In 1918, Jones left her work at Women’s College in Hattiesburg and entered serious public health work, appointed by Dr. Boswell to assist his medical work as superintendent of the newly opened Mississippi State Sanatorium for tuberculosis. Boswell later placed her in charge of travelling x-ray clinics, which was a critical part of the diagnosis of tuberculosis in the general population. She was a beloved and respected figure in the early days of the Sanatorium. She retired from her work at the Sanatorium due to “ill health” in 1929, and moved first to Laurel to live with her son Malcolm (1888-1938) and daughter-in-law Nora Fleming (1890-1966), then later back to her hometown of West Point, Virginia, where she took an active part in local civic matters and the work of the community Episcopal Church where she was a member. Her son Edgar Malcolm appears to have died prior to her own death, and her obituary notes that she was survived by two grandsons in Laurel: Edgar Malcolm (1915-1997) and Bruce Odell Jones (1918-1965). She had two great-grandchildren Douglas Malcolm Jones (1944-2002) of Laurel and Suzanne Johnson (1947-) of Laurel, and a great-great granddaughter Elizabeth Aaron Jones of Oxford. After her death, she was buried at Sunny Slope Cemetery in West Point, Virginia.9,10

Another prominent early member of the MSMA was Sara Allen Castle, MD (1861-1938), who joined a year or so after Jones and Wiss. The 1905 MSMA Transactions reveals two women in leadership roles as “Chairmen of Sections”: Dr. Sara A. Castle of Meridian, Chairman of Gynecology, and Dr. May Farinholt Jones of Columbus, Diseases of Children.11 Dr. Castle, a Choctaw County native, was the daughter of Rev. Thomas Castle (1819-1893) and Zemely Josephine Corkern Castle (1833-1881). The Meridian Evening Star in November 1902 noted her late October arrival in Meridian to East Mississippi Female College, a Methodist institution (which was recognized as one of the finest female colleges in the South): “Dr. Sara Allen Castle, the new college physician has arrived at E. M. F. College. Dr. Castle is a native of Mississippi, is a graduate in the literary course, and also a graduate in Medicine from the Cornell Medical College and took post-graduate work in the Johns Hopkins University at Baltimore. She has had charge of a hospital in Baltimore for a year or two as resident physician, has had large experience, and is quite an addition to the faculty of the E. M. F. College. Dr. Castle will teach physiology and will give lectures to young women on health and how to take care of themselves and will be a great help in preventing sickness and looking after the sanitary surroundings of the college. This is a step forward for this excellent institution. Dr. Castle will likely do city practice later on after she rests from her heavy work that she has been doing in Baltimore.” An earlier announcement noted that this “accomplished and experienced physician” will “live in the college where she can give her attention to students or teachers at all hours, day or night.” The newspaper reflected, “It will be very fitting to have a woman physician to give plain talks to young women about how to care for health, such as a man could not well give with propriety. This is quite an advantage move on the part of the college.”12,13 She was hired by progressive college president John Wesley Beeson, a widely admired Mississippi educator. Unfortunately, the college was destroyed by fire on February 24, 1903. Castle appears to have gone into private medical practice in Meridian after the fire.

In 1909, Castle achieved national recognition with her prescient observation at the National Association for the Study and Prevention of Pellagra meeting in Columbia, South Carolina, when she asserted dietary causes of the disease. One state newspaper reported, “One of the most interesting addresses of the conference was delivered tonight by Dr. Sara A. Castle, of Meridian, Miss., who made the somewhat startling statement that of the many cases of pellagra which she had treated since it was first recognized in Meridian six of the patients were socially prominent in the city and five of these died. It is not necessarily a disease confined to the poor, according to a prevailing popular impression, declared Dr. Castle. All of her patients were eaters of corn bread and grits. She stated also that several of her hook worm patients subsequently developed pellagra and died.”14 She became a state expert on pellagra, giving medical presentations and occasional commentary to the press. She began seeking novel treatments for pellagra, accompanying a patient to a Mobile hospital to undergo a “transfusion of blood in an effort to counteract the ravages of pellagra.”15 Over several years, her study of the disease was becoming helpful in solving pellagra’s riddle. After attending the meeting of the Southern Medical Association in Hattiesburg in 1911, Dr. Castle was quoted asserting her “corn theory” as pellagra’s cause: “Dr. Castle is a close student of pellagra and relates an interesting story of several chickens on exhibit at the meeting which she claims lays all doubt that pellagra is due to the use of spoiled corn.”16 Castle, like Dr. Joseph Goldberger later, recognized that the cause of pellagra was not infectious but rather dietary in origin and related to corn, a key concept in understanding the disease which was ravaging Southern orphanages, known to provide the so-called corn-centric “mill diet.” In 1914, her work with pellagra was again recognized in the state press: “Dr. Sara A. Castle, who is an interested student of this disease, has written Dr. McKernon, head of the commission, requesting he comply with Meridian’s invitation.”17 McKernon was head of a pellagra commission stationed in South Carolina, and Castle asked their assistance studying the high number of cases in Meridian. Castle continued positive work on this disease over many years.

Castle’s office in Meridian was located on the second floor of the three-story Ormond Building in Meridian, which was situated at the corner of Twenty-second Avenue and Fourth Street.18 She appears to have been a member of the Central Methodist Episcopal Church in Meridian and ran a free clinic at the church beginning in 1910, a novel concept at the time. A newspaper reported, “Dr. Sara Castle will give two hours of her time every Saturday afternoon to seeing and prescribing for patients. This service is free to those unable to pay and other patients are charged a nominal sum.”19 Six years later, the success of the free clinic was acknowledged in a local newspaper, which reported, “In January, 1910, Dr. Sara Castle opened a free clinic…and treated patients there and did any surgical work necessary. At this time the work has grown to such proportions that we felt the need of more room and also of a trained worker.”20 She liked to spend her summer vacations in Mississippi City on the Gulf Coast fishing, armed “with a twenty-foot bamboo fishpole, equipped with line, hook, sinker, and cork, and with a shiny tin pail packed full of ice-cold shrimp.” The Sun Herald wrote, “Dr. Sara A. Castle of Meridian, a summer visitor in Mississippi City, braves the sunshine and the perils of the fishing piers three times a week, and seldom returns without a string of fish that would stimulate the envy of any case-hardened scientific angler.”21 Castle would never marry. She would finish out her career working as resident physician at Mississippi State College for Women in Columbus,22 before her death on August 22, 1938. She is buried in Magnolia Cemetery in Meridian.

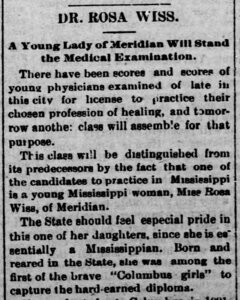

The final prominent pioneer physician in Mississippi is Dr. Rosa Douglass Wiss, the first female to be licensed as a physician in Mississippi. She was born July 15, 1868, in South Carolina, one of several children of farmer E. Jefferson and Mary Hodges Wiss, natives of South Carolina who by 1880 had moved from Charleston, South Carolina, to Lauderdale County, Mississippi.23 As far as the spelling of her name, despite frequent misspellings in the press and MSMA records as “Weiss,” it is clearly “Wiss,” as spelled on her tombstone, other family records, and the Meridian City Directories of the period.24

When the State Board of Health convened in Jackson in October of 1895, the press closely monitored their actions as they considered for the first time a young woman to be examined and licensed, a process which began in 1882.25,26 One newspaper reported from Jackson, “The State Board of Health convened here to-day. To-morrow the board will sit as medical examiners to give young men who desire to practice medicine an opportunity to tell what they know about the intricacies of the profession. It is thought a large number of applicants will be on hand. Miss Rosa Wiss of Meridian, an excellent young woman and a graduate of the Industrial Institute and College at Columbus is an applicant before the State Board of Health for license to practice medicine. As she is the first woman to ever ask for license in Mississippi her success in procuring the same will be closely watched.”27,28

The Clarion-Ledger was enthusiastic in its reception of Wiss: “There have been scores and scores of young physicians examined of late in this city for license to practice their chosen profession of healing, and tomorrow another class will assemble for that purpose. This class will be distinguished from its predecessors by the fact that one of the candidates to practice in Mississippi is a young Mississippi woman, Miss Rosa Wiss, of Meridian. The State should feel especial pride in this one of her daughters, since she is essentially a Mississippian. Born and reared in the State, she was among the first of the brave ‘Columbus girls’ to capture the hard-earned diploma. She graduated at Columbus in 1891 after which she went to the Woman’s Medical College in Philadelphia, where she has since prosecuted her studies, and from which she graduated this summer. Mississippi has had several daughters to follow in Aesculapius’s steps, but never one like this one, content to return to Mississippi after her years abroad, to practice her profession. Miss Wiss, following the advice of the physicians of Meridian, has determined to settle there, and has already begun to build up quite a pleasant and lucrative practice. Her specialty is diseases of women and children and she gives promise of making her name famous in the work. There is no doubt of her ability to pass the required examination and the women of the State— particularly those who were with her at the I. I. & C., will rejoice greatly in her success.”29 An Indianola newspaper echoed similar news, revealing its general interest to state readers: “Miss Rosa Weiss <sic>, of Meridian, has applied to the board of medical examiners for license to practice medicine in this State.”30 Soon afterwards, the Yazoo Herald announced, “Miss Rosa Weiss <sic>, of Meridian, was granted license by the State Medical Board Tuesday in practice medicine in Mississippi, and is now a full-fledged physician. Her examination was creditable. Miss Weiss graduated in 1891 at the Industrial Institute and College at Columbus and later at the Women’s Medical College in Philadelphia. Dr. Weiss is a native Mississippian, and in entering upon the practice of her profession she has the best wishes of every Mississippian for success.”31 The Kosciusko Star Ledger helped future historians clarifying her “first” licensed status by stating frankly that “[s]he is the first lady that ever applied for an M. D. license in this State,” which also suggests that this was an assertion of the State Board of Health in 1895.32

Wiss’s accomplishment in 1895 received national attention and provided a great inspiration to young Mississippi and American women aspiring to become physicians, and within a few years a large number of women would follow in her footsteps. Suffragist Belle Kearney (1863-1939) included a celebratory sketch of Dr. Wiss in her book A Slave Holder’s Daughter (1900): “A striking instance of the energy and persistence of the Southern character is shown in the case of a young woman born in South Carolina and brought by her parents at the age of seven years to Mississippi, where she was reared on a farm near Meridian. From her earliest years she was possessed of a great love of natural science, and was filled with an ambition for a liberal education; but she was poor, and the future looked shadowy and forbidding. It was not so dark, however, as not to be overcome by a relentless energy. At one time her brother playfully gave her the large sum of 5 cents. With this she bought a yard of calico out of which she manufactured a sun-bonnet, and sold it for 25 cents. That amount she invested in more calico, and made and sold a dress. The reinvestment followed till $12 was realized. She then persuaded her father to let her have an acre of land to cultivate for a year; and from her own labor and the help of the $12 she raised a crop of sweet potatoes that netted her $40. This amount just covered the required deposit necessary to enter the Industrial Institute and College at Columbus, Miss. Here she paid her board for four years by doing dining-room work. In 1891 she graduated with the degree of B. A. The next year was passed in Meridian, studying medicine under one of the leading physicians. In the fall of 1892, she entered the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, paying her way through the institution by giving private lessons in physiology and chemistry to the students, for which she received $2 an hour, and at odd times working as a waitress in a restaurant. During the summer she stayed in Philadelphia nursing, thus making her expenses and gaining much practical knowledge. In 1895 she graduated from the Pennsylvania Woman’s College, and returned at once to Meridian. Very soon she was requested by two mission boards to go to China and take charge of hospital work there; but she said she felt called to practice medicine in the South, in her own State and among her own people. Six months after her graduation as a physician, she took the State medical examination, and was granted a license to practice— the first woman in Mississippi who had gained such a distinction. Her reception by the physicians of her State has been cordial and courteous. Dr. Rosa Wiss is now an honored and independent physician with an assured success.”33

A monthly magazine called “Success” published a later version of Kearney’s sketch of this “prominent lady physician of Meridian”: “A few years ago, Miss Rosa Wiss was poor, but also ambitious; now she is an M. D. and has a lucrative practice. She asked her brother to send her to college. He told her that he could not afford to do that, but, giving her five cents, jestingly said to her, ‘Go on that!’ She saw wonderful possibilities in that nickel. With it she bought a yard of calico from which she made a sun-bonnet. Selling the sunbonnet for twenty-five cents, she bought material for bonnets and aprons. In this way several dollars were realized. Her brother, pleased with her thriftiness, gave her some land, which she planted in sweet potatoes, cultivating it with the assistance of a small boy. The products of the first year brought her forty dollars. Later she entered a state educational institution where she remained until she graduated with honor. During the course she received some assistance from an aid society, all of which was repaid. Miss Weiss entered the medical college at Baltimore, Maryland, where she paid her tuition by nursing and was graduated from there with honor. She is now a practicing physician in Meridian, Mississippi, near her former home, and her income is a good one.”34–36

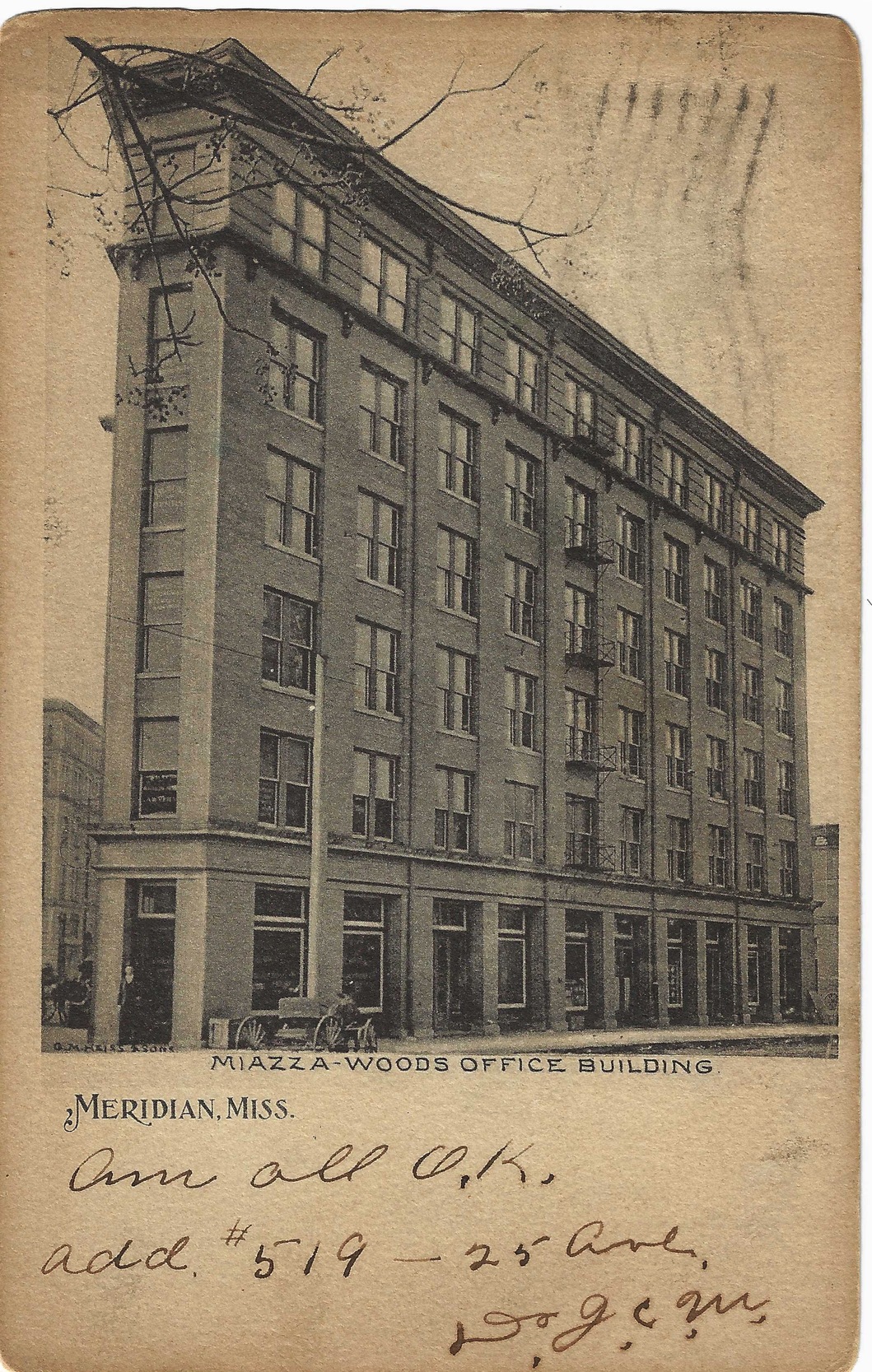

While Wiss’s prominence did not match Jones and Castle during her professional career, she did deliver papers at MSMA annual sessions and maintained a practice in Meridian for more than three decades.37 She practiced in Meridian at the iconic Miazza Woods building (420-1), see photo, until her death in 1931. Her residence in Meridian was 2322 15th Street, where she lived with her sister Victoria, and neither ever married. She died September 13, 1931, in Meridian and was buried in Semmes Cemetery in Meridian in her family’s plot. Her stone there features the hand of God holding a broken link of chain, an ancient cemetery symbol representing the loss of a beloved family member.

Although she was the first licensed physician in Mississippi, Wiss may not have been the first female to practice medicine, at least in limited capacities in the state. Dr. Florence L. Dickerson, a Holly Springs, Mississippi native, who received her medical degree from the St. Louis Eclectic Medical College in 1882, is reported to have practiced medicine in the Mississippi towns of Salem, Ashland, and Hudsonville during her time of practice, beginning in 1882. She died in May of 1929 at Holly Springs.1,38 Another early female physician said to have practiced early in Mississippi was Verina Morton Harris Jones, MD, an African American physician who located in Holly Springs at Rust College from 1888 to 1890. She went to Holly Springs after graduation from Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1888. Although the records at Rust are inconclusive and sparse, a long oral tradition maintains her presence there with the college’s attempt to establish a “medical program,” which began in the 1870s and lasted until the mid 1890s and the institution’s “hosting” of a female physician during that period. Historians have asserted that Morton Jones was “the first woman, Black or white, to practice medicine in the state of Mississippi.”1,39,40 In the 1890s, Holly Springs native Anne Walter Fearn founded the first co-educational medical school in China.1 Other early female physicians of note are Georgia A. Proctor, MD, an African American, who began her practice in Vicksburg in 1903 and who appears to be the first female member of the Mississippi Medical and Surgical Association; Daisy Estelle Brown Bonner, MD, who was the first African American female from Mississippi to obtain an MD in 1907; and Margaret Roe Caraway, MD, who in 1910 became the first female graduate from a Mississippi medical school (Meridian).1,41

Other early MSMA female members included Dr. Alma Matilda Lautzenhiser Rowe (1868-1906) of Scott County and Katy Allen of Tate County. Rowe, a Nebraska native who graduated from Northwestern University Women’s Medical School in 1893, obtained her Mississippi license in 1903. She practiced in Hillsboro and Forest in Scott County and served as Secretary of the Scott County MSMA Component Society before her death on May 27, 1906. Her husband, Dr. Ellis Jay Rowe (1861-1931), had moved with her from Crete, Nebraska to Forest, Mississippi in 1900, hoping the warmer climate might help his asthma. The couple later moved to Hillsboro with their five children. The couple are buried at Forest’s Eastern Cemetery. After her death, her hometown newspaper in Nebraska reprinted an obituary taken from the Scott County Register, which stated, “The remains were brought to Forest Sunday morning, the casket covered with beautiful floral offering from friends at Hillsboro, Forest and other places, taken to the Methodist church, where the funeral service was conducted by Rev. W. W. Morse in an effective and comforting manner. The pallbearers were physicians of the Scott County Medical Society, of which she was an honored member and secretary. Alma M. Lautzenheiser was born in Illinois May 14, 1868. When she was small her people moved to Nebraska, which state she made her home until the fall of 1900, when she removed with her husband to Mississippi. In 1892, she was married to Ellis J. Rowe, and in 1893 she was graduated from the Woman’s Medical School of Northwestern University, at Chicago, since which time she has divided her attention between her practice of medicine and the care of her family. She was reared in a Christian home and in her early years gave herself to Christ, uniting with the Baptist Church at Dorchester, Nebr. Later she united with the Christian Church. Her whole life was spent in doing good, for she loved that which was good and hated that which was false. She was always active in church and Christian work when living where opportunity presented.”42 Little is known about Allen outside of her mention in early transactions.

The records of the State Board of Medical Licensure are difficult to access as are early records at county courthouses, where licenses were registered. A review of early newspapers in the state reveals the presence of many other female physicians, both allopaths and osteopaths, who have escaped notice. As early as 1901, the Drs. Haley were in osteopathic practice at the Rosenbaum Building in Meridian, one of which was “Mrs. Ruth K. Haley, D.O.”43 Soon, the practice was simply hers, and she maintained a vigorous osteopathic practice in Meridian for thirty years. Dr. Haley’s advertisement in the Meridian Press stated, “Dr. Ruth K. Haley, Osteopathic Physician. Over two years successful practice in Meridian. Special attention given to disease of women and children. Nervousness, poor circulation, and all Liver, Stomach, Bowel, and Kidney troubles relieved by our treatment. No poisonous medicines used. Office No. 13, Mason Temple Building.” Her office was later on the fifth floor of the Miazza Woods Building.44 Osteopathic physicians were not licensed by the Board of Health at that time, and Haley was among the first female DOs in practice in the state. More research is needed to explore fully the emergence of female physicians in Mississippi in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. If you have an old or even somewhat recent photograph which would be of interest to Mississippi physicians, please send it to me at drluciuslampton@gmail.com or by snail mail to the Journal. — Lucius M. “Luke” Lampton, MD; JMSMA Editor

_in.jpg)

_in.jpg)